FREE DEMOCRAT FREE SPIRIT

A philosopher has just fought a free election in Hungary.

Charles Moore joined him Budapest `WHEN I was a boy,' Gaspar Miklos Tamas told me, 'my idea was to be Doge of Venice, because of the aquatic festivities, and because I was dotty about the sea.' As he spoke, however, he was happily under- going the less glamorous proceedings of democracy in a land-locked country. He was standing as the candidate of the Free Democratic Alliance in this city's first genuine election (a by-election) in modern times.

Gaspar Tamas was born in 1948 in Transylvania. He is Hungarian, and his home-town, Kolozsvar, is Hungarian too, but it was and is ruled by Rumania, which calls it Cluj. Dr Tamas's parents were communists, but already, by then, disillu- sioned ones. His father was a journalist and theatre manager, a Roman Catholic by upbringing. His mother was the daughter of a Jewish cantor. Both parents repudi- ated religion. When he decided at the age of 16 that he was a Christian, he kept his baptism secret from them.

In what he calls 'my lonely Victorian childhood', Gaspar read and read. His whole formal education was received in Kolozsvar, his real one picked up from what he could scavenge, particularly from pre-war German books found second- hand. As well as German, he taught himself Latin and Greek, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian and English. His strongest early intellectual influence was German Romanticism.

It was not surprising that Kolozsvar could not long supply him with the work he sought. After four years co-editing a liter- ary review there, Gaspar was demoted to the rank of proof-reader because he re- fused to write an article praising Ceauces- cu's 'moral code'. He was banned from publishing, although he managed to evade the ban with a commentary on Descartes' Discourse on Method.

From then on Dr Tamas was interro- gated three or four times a week by the security police. In 1978 he left for the relative freedom of Hungary and, after a period of unemployment, was made a lecturer in the history of philosophy at Budapest University. Here too, however,

ideology soon intervened. His university colleagues let him teach Aristotle's Metaphysics in peace, but the Communist Party was not happy with his 'oppositional activities'. The Ministry of Education ordered that his contract be not renewed in 1982. From that time until three months ago, when the university restored his job,

he was unemployed. It was not until 1986 when, after international lobbying, he was granted a passport, that this citizen of the world was permitted to see any of it for himself. He won a scholarship to the University of Columbia: his first sight of a free place was of New York.

At this time, Gaspar Tamas's interest in English thought and writing was develop- ing fast. His observation of politics led him to conclude that the 'dark and cloudy philosophy' of the German Romantics 'won't do'. He admired the works of Hume, of William Godwin ('I remember it now shuddering'), the essays of Lamb and Leigh Hunt. At Columbia he studied the history of British conservatism. In 1987 he came to Oxford, and in the same year

married an English journalist, Nina Elston, of whom he now has a daughter. He recalls how intensely proud he was to be given lunch by Sir Isaiah Berlin at the Athen- aeum. Even the Church of England appealed to him ('I like the way you can be High and Low in the same Church without qualms') and he became a serious student of the Oxford Movement. By 1988, The Spectator was benefiting from his occasion- al contributions. There, and in more ex- tended essays, essays which unfortunately still lack an English publisher, Dr Tamas has developed a liberal Toryism and sought to apply it to the situation in Eastern Europe.

And now that application can be made not only abroad or in samizdat argument, but in electoral debate. Gaspar's party, the Free Democratic Alliance, is the second largest opposition party in Hungary. It rejects the belief of its bigger rival, the Hungarian Democratic Forum, that there is a 'third way' between communism and the West. It is 'unashamedly pro-Western'. Its manifesto calls for 'a free market economy based on unlimited competition and private property'. Because of Hungary's lack of appropriate political tradition, the FDA reluctantly favours a written constitution, but its preferred form of government is more parliamentary than presidential, more British than American. It would have a strong judiciary, no iden- tity cards, no national police force. The Free Democrats would take Hungary out of the Warsaw Pact. They would not campaign to expand Hungary's shrunken borders, but, says Dr Tamas wistfully, 'Austro-Hungary was a marvellous thing.' marvellous thing.'

Last week, Gaspar Tamas brought these arguments to the 18,000 constituents of Lipotvaros (Leopoldstadt), the very centre of Pest, an area dominated by Jews until, during the terrible siege of Budapest at the end of the war, Hungarian fascists took them out and shot them. Now it is an area of people who are mostly rather poor and rather old.

Some of them were confused about the election, as the authorities intended that they should be. It fell due in the summer and its date was repeatedly delayed. It was held on a Saturday instead of the expected Sunday. The campaign was not properly reported on television. Campaigning was forbidden on polling day and on the day before, so people had time to forget about voting.

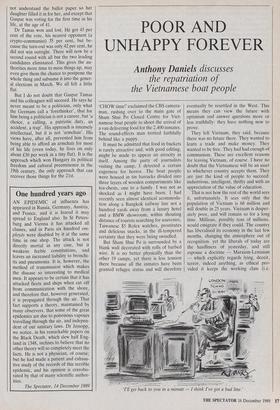

Many seemed wary of politics and con- fused about what was on offer, not caught up in the recent heady enthusiasm of Czechoslovakia or East Germany. Canvas- sing with Gaspar in the markets and shops reminded me of doing the same thing in England: it was low-key, hesitant, court- eous, faintly embarrassing. I went to watch Gaspar vote and that too was like England — a quiet affair in a dull civic building — except that I noticed an old woman could

not understand the ballot paper so her daughter filled it in for her, and except that Gaspar was voting for the first time in his life, at the age of 41.

Dr Tamas won and lost. He got 45 per cent of the vote, his nearest opponent (a crypto-communist) 35 per cent, but be- cause the turn-out was only 42 per cent, he did not win outright. There will now be a second round with all but the two leading candidates eliminated. This gives the au- thorities more time to mess things up, may even give them the chance to postpone the whole thing and subsume it into the gener- al elections in March. We all felt a little flat.

But I do not doubt that Gaspar Tamas and his colleagues will succeed. He says he never meant to be a politician, only what the Germans call a lorethinkee, that for him being a politician is not a career, but 'a choice, a calling, a patriotic duty, an accident, a trap'. His approach is intensely intellectual, but it is not 'armchair'. His views have, after all, prevented him from being able to afford an armchair for most of his life (even today, he lives on only about £30 per week in a tiny flat). It is the approach which won Hungary its political freedom and cultural preeminence in the 19th century, the only approach that can recover those things for the 21st.

Previous page

Previous page