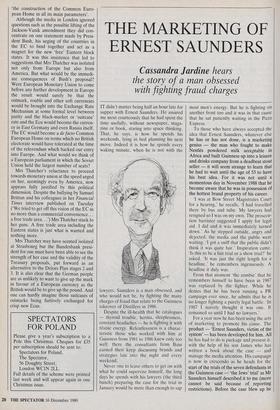

THE MARKETING OF ERNEST SAUNDERS

Cassandra Jardine hears

the story of a man obsessed with fighting fraud charges

IT didn't matter being half an hour late for supper with Ernest Saunders. He assured me most courteously that he had spent the time usefully, without newspaper, maga- zine or hook, staring into space thinking. That, he says, is how he spends his weekends, lying in bed planning his next move. Indeed it is how he spends every waking minute, when he is not with the lawyers. Saunders is a man obsessed, and who would not be, by fighting the many charges of fraud that relate to the Guinness takeover of Distillers in 1986.

Despite the ill-health that he catalogues — thyroid trouble, hernia, sleeplessness, constant headaches — he is fighting it with titanic energy. Relentlessness is a charac- teristic those who worked with him at Guinness from 1981 to 1986 knew only too well: there the consultants from Bain earned their keep discussing brands and strategies late into the night and every weekend.

Never one to leave others to get on with what he could supervise himself, the long days he spends with his lawyers (the third bunch) preparing the case for the trial in January would be more than enough to sap most men's energy. But he is fighting on another front too and it was in that cause that he sat patiently waiting in the Pizza Express.

To those who have always accepted the idea that Ernest Saunders, whatever else he has or has not done, is a marketing genius — the man who fought to make Nestl6s powdered milk acceptable in Africa and built Guinness up into a leisure and drinks company from a deadbeat stout seller — it will seem strange to learn that he had to wait until the age of 53 to have his best idea. For it was not until a momentous day in November 1988 that he became aware that he was in possession of the hottest brand property of his career.

'I was at Bow Street Magistrates Court for a hearing,' he recalls, 'I had travelled there by bus and tube. My lawyers had resigned so I was on my own. The prosecu- tion barrister suggested I apply for legal aid. I did and it was immediately turned down.' As he stepped outside, angry and dejected, the media and the public were waiting. 'I got a sniff that the public didn't think it was quite fair.' Inspiration came. 'Is this to be a fair trial or a show trial?' he asked. 'It was just the right length for a headline,' he remembers ingenuously. A headline it duly was.

From that moment 'the zombie' that he remembers himself to have been in 1987 was replaced by the fighter. While he denies that he has been running a PR campaign ever since, he admits that he is no longer fighting a purely legal battle: 'In 1987 I naïvely thought it was one. It remained so until I had no lawyers.'

For a year now he has been using the arts of marketing to promote his cause. The product — 'Ernest Saunders, victim of the system' — has been developed for him. All he has had to do is package and present it. with the help of his son James who has written a book about the case — and manage the media attention. His campaign is now in crescendo as he heads for the start of the trials of the seven defendants in the Guinness case — 'the Jews' trial' as Mr Saunders himself described it to me (more cannot be said because of reporting restrictions). Before the case blew up he

was never part of the Kosher Nostra but after the event the behaviour of the Establishment figures in the City and in Edinburgh has led him to brand them the 'double-barrelled shotgun' and make much of how it has been held to his head.

By January, he confides, 'a lot has to be written — in other circumstances I would do it myself and it has to be written despite a ban placed by the Attorney General in September on press reporting of the case and in defiance of his lawyers' disapproval of his 'extra-curricular activities'.

This is the background to a long supper around the corner from his lawyers in Bedford Square, in which little is eaten, only mineral water drunk, but many pages covered by notes as Ernest dictates the 'for your ears only — I want you to understand the full story' background to the latest stage in the campaign. As presentations go, it is pared down to its bare essentials. Gone are the flip charts and light shows of de luxe marketing, instead he offers sincerity, clarity and the unique selling proposition of access to a notorious figure of our time He starts by establishing the appeal of the product. 'On my way here I was stopped by three people who wanted me to sign copies of my son's book and two who wanted my autograph. People are embarrassed by what I am going through.'

There follows a two-hour account care- fully, patiently recited at dictation speed to support the main selling points of his predicament. The first is that 'I wouldn't be going to these lengths to defend myself if I wasn't innocent', the second that 'what happens to me is now of secondary import- ance. What I really care about is justice.'

Invoking Dreyfus, Judge Pickles, John Stalker and the Guildford Four, Saunders presents himself as the latest in a long line of victims, a man sacrificed to help the Conservatives win the 1987 election. He throws in David and Goliath for good measure.

He would do well on a quiz show in which prizes were awarded for no devia- tions and no hesitations. The words come out in a continuous stream and, from the intent look in his eyes, he is no more wondering how the message is being re- ceived than he is sidetracked by which pizza to order. In the end he chose one with a lot of health-giving spinach and left most of it — something to do with thyroid trouble, he explained.

Since the blinding conversion to self- marketing, Saunders has been able to take advantage of a series of thermals to keep his case soaring. There has been the resignation of the lawyers and the repeated denials of legal aid, among other delays.

'People have understood: four years of suffering [it will be by the time the trial is over] and the terrible way I have been treated.' The latest piece of ill-fate to play into his hands is the rush to put together his case in time for January, which means he has to ignore the orders of doctors who, he claims, say he should only be working five hours a day, four days a week.

While each twist of the plot against him provides him with a new grievance he keeps in view the long-term goal: 'Those who are involved in the prosecution should be afraid to be involved in a miscarriage of justice.' In practical terms to Saunders this means, 'if I need more time I should be given more time.'

To whip up the sympathies of the man in the street, Saunders needs the help of the press whose favour he learned to court in 1984 when he wanted publicity for his achievements at Guinness. Under expert advice he arranged one-to-one briefing sessions, normally over breakfast, knowing that it is faces, not figures that make good copy. Ernest Saunders knows, or thinks he knows, how to manipulate the press. If these days he is cynical it is not surprising: came the fall, few journalists stood up for him — perhaps because he made them feel like pawns in his game. These days he blatantly makes use of his misfortunes, 'No home, no money and a hernia too', to gain sympathy and column-inches at carefully spaced intervals in the publications which he believes will suit his purposes.

He has a series of techniques. The first is the assumption that you are on his side, there being no middle ground for Saunders between allies and enemies. With that in mind he speaks as one manipulator to another: 'Your readers are the ones I want to reach. The interest in this subject is too narrowly confined to the City pages,' he says referring to Telegraph features rather than The Spectator. The second is flattery: 'I'm telling you this because the piece you

wrote about me before was a superb piece of journalism.' The third is the threat: 'If you don't publish this then I shall give the story to someone else.'

Having finished his account of the injus- tices of the past three years, he provides his analysis of the true reasons for the current embargo on reporting, and proceeds to the nub of the matter.

'Read your notes carefully,' he advises paternally, 'and then we'll discuss how and where you write an article (what you write is of course your business). There are two ways it could be done. Since Judge Henry has banned reporting you could say that I have (you have) some concerns about the trial. . . . Or you could do a piece: My Concerns for Justice as told to. . . . Provid- ing you stick to the worries about the process and avoid the specifics of what's happening in the courtroom today you should be all right. Ask yourself whether this would be a better Telegraph than Spectator piece. James and I will help you achieve what you want to achieve and James can advise you on getting it past the lawyers.'

There is a naivety about Saunders which is strangely touching, a trust that people can be pushed into the required shape like so much plasticine, but which makes him annoying even in misfortune. Even in his current state he has a kind of power, a power that comes not just from being a large man but from focussing on one thing and focussing on it ceaselessly. He seems to believe that you can always be doing something more to get what you want. The trial will decide whether that is why things went wrong at Guinness.

Cassandra Jardine is assistant features editor of the Daily Telegraph.

'Miss Nathan, find out what a lifestyle is and then get me one.'

Previous page

Previous page