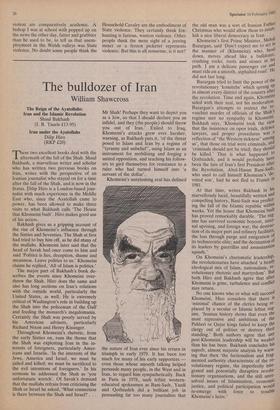

The bulldozer of Iran

William Shawcross

The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution Shaul Bakhash (I. B. Tauris £13.95) Iran under the Ayatollahs Dilip Hiro (RKP £20) 'These two excellent books deal with the 1 aftermath of the fall of the Shah. Shaul Bakhash, a marvellous writer and scholar who has written two previous books on Iran, writes with the perspective of an Iranian journalist who stayed on for a time after the fall of the Shah, and is now in the States. Dilip Hiro is a London-based jour- nalist with much experience in the Middle East who, since the Ayatollah came to power, has been allowed to make three visits to what Bakhash calls 'The House that Khomeini built'. Hiro makes good use of his access.

Bakhash gives us a gripping account of the rise of Khomeini's influence through the Sixties and Seventies. The Shah at first had tried to buy him off, as he did many of the mullahs. Khomeini later said that the head of Savak had once come to him and said 'Politics is lies, deception, shame and meanness. Leave politics to us.' Khomeini claims he replied, 'All of Islam is politics.'

The major part of Bakhash's book de- scribes the events since Khomeini over- threw the Shah. Hiro does the same and also has long sections on Iran's relations with the outside world, particularly the United States, as well. He is extremely critical of Washington's role in building up the Shah into the policeman of the Gulf and feeding the monarch's megalomania. Certainly the Shah was poorly served by his American advisers, particularly Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

Throughout Khomeini's rhetoric, from the early Sixties on, runs the theme that the Shah was exploiting Iran in the in- terests of foreigners, particularly Amer- icans and Israelis. 'In the interests of the Jews, America and Israel, we must be jailed and killed; we must be sacrificed to the evil intentions of foreigners.' In his sermons he addressed the Shah as 'you unfortunate wretch'. Of Savak's demand that the mullahs refrain from criticising the Shah or Israel he asked, 'What connection is there between the Shah and Israel? . . . Mr Shah! Perhaps they want to depict you as a Jew, so that I should declare you an infidel, and they (the people) should throw you out of Iran.' Exiled to Iraq, Khomeini's attacks grew ever harsher, warning, as Bakhash puts it, 'of the threat posed to Islam and Iran by a regime of "tyranny and unbelief", using Islam as an instrument for mobilising and forging a united opposition, and teaching his follow- ers to gird themselves for resistance to a ruler who had turned himself into 'a servant of the dollar'.

Khomeini's unrelenting zeal has defined the nature of Iran ever since his return in triumph in early 1979. It has been too much for many of his early supporters even those whose smooth talking helped persuade many people, in the West and in Iran, to regard him sympathetically. Back in Paris in 1978, such leftist western- educated spokesmen as Bani-Sadr, Yazdi and Qotbzadeh did a brilliant job in persuading far too many journalists that the old man was a sort of Iranian Fattier Christmas who would allow them to estab- lish a nice liberal democracy in Iran. Khomeini's first Prime Minister, Mehd.1 Bazargan, said 'Don't expect me to act le the manner of (Khomeini) who, head down, moves ahead like a bulldozer., crushing rocks; roots and stones in his path. I am a delicate passenger car and must ride on a smooth, asphalted road.' He did not last long. Bazargan tried to limit the power of the revolutionary icomitehs' which sprang uP in almost every district of the country after the revolution. Time and again, Khomeini sided with their zeal, not his moderation. Bazargan's attempts to restrict the 1.- vanchist murder of officials of the Shahs regime met no sympathy in Khomeini. Bakhash says, 'Khomeini took the view that the insistence on open trials, defence lawyers, and proper procedures was a reflection of "the Western sickness" among us', that those on trial were criminals, and, 'criminals should not be tried; they should be killed.' That is what happened in Qotbzadeh, and it would probably have been the fate of Iran's first President after the Revolution, Abol-Hasan Bani-Saclr, who used to call himself Khomeini's 'de- voted son', had he not fled to France In 1981. At that time, writes Bakhash in his, marvellously lucid, beautifully written and compelling history, Bani-Sadr was predict- ing the fall of the Islamic republic within weeks. Yet the house that Khomeini built has proved remarkably durable. 'The reg- ime has survived economic boycott, inter- nal uprising, and foreign war; the destruc: tion of its major port and refinery facilities, the loss through purge and emigration of its technocratic elite; and the decimation of its leaders by guerrillas and assassination squads.' On Khomeini's charismatic leadershili, the revolutionaries have attached 'a heady ideological mix of Islam, nationalism, re- volutionary rhetoric and martyrdom'. But both Hiro and Bakhash agree that after Khomeini is gone, turbulence and conflict may return. No one knows who or what will succeed I Khomeini. Hiro considers that there s 'minimal' chance of the clerics being re- placed by a secular or Islamic leftist reg- ime. 'Iranian history shows that even the most repressive and ambitious of the Pahlavi or Qajar kings failed to keep die clergy out of politics or destroy their standing.' Both authors agree that any post-Khomeini leadership will be weaker than his has been. Bakhash concludes his superb, almost majestic analysis by warn' ing that then 'the factionalism and frag- mented authority characteristic of the re- volutionary regime, the imperfectly inte- grated and potentially disruptive revolu- tionary organisations, and the still unre- solved issues of Islamisation, economic justice, and political participation would re-emerge with force to trouble Khomeini's heirs.'

Previous page

Previous page