ARTS

Art

This blinkered isle

Andrew Solomon on the xenophobia of the British art establishment

Mrs Thatcher, taken to an interna- tional art exhibition last year, asked, in a tone that seemed to imply that she was interested only in what was evidently su- perior, 'Where is the British art?' Perhaps premiers are obliged to carry their nationalism into the arena of culture, but cultural institutions suffer under no such obligation, and though only Mrs Thatcher would actually come out and ask that question in that tone at an ostensibly international event, it is one that is echoed constantly across Britain by critics, cura- tors, dealers, artists and museum directors. Of course it is true that if the British do not nurture their own artists, they can hardly expect these men and women to win approbation abroad; it would be sad in- deed if the British simply didn't care about British artists. But the 'British is better' attitude betrays a xenophobia that is every bit as unappealing in the cultural arena as it is when it manifests itself in racial violence.

The last strain of romanticism in Britain is revealed in the much vaunted popular supposition that beauty is truth, and that art should, therefore, be easy and pleasur- able. No other country in the West, at this moment, boasts such a panoply of attrac- tive pictures to hang up and look at as Britain; all of these are taken seriously by a vast, popular art establishment. And while the British art market and its partisans insist on beauty, the 'art elite' signifies its superiority by favouring a narrowly intel- lectual form of art, thereby allying itself with a spurious, mainly European and American internationalism.

Though art is and can be and should be engaged with issues of beauty and of the intellect, beauty and intellect in themselves do not make artistic activity. The function of a work of art is communicative, and communication requires effort at a variety of levels, effort not only from the person who is communicating, but also from the object of that communication. This effort is an effort of the senses, of the mind and of the heart. Lucretius defined the sublime as the art of exchanging easier pleasures for more difficult ones; it is easy to love what is beautiful, and it is reasonably easy to engage with someone else's intellect, but it is hard work to understand someone's vision, motivation, belief system and emo- tion. And the further these great abstracts are from your own vision, motivation, belief system and emotion, the harder the engagement becomes.

The British response to work coming out of other countries arid other-than- mainstream experiences is wildly and dis- tressingly unsympathetic. Before the mid- Eighties, artists in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union created works of art because they saw themselves as protectors of the truth at a time when the bodies of power were going to great lengths to abrogate truth itself. Recent political events have made it possible for them to bring out the truths they guarded — the truths of their own dignity, of a humanity that misplaced ideology could not nullify — and expose them to the world. Work by artists living under totalitarian regimes in the Third World does much the same thing. Aids- related art — some of the best examples of which have been manufactured by British artists — is only a variation on the theme. All this art has come out of a visionary gleam in the context of pain. We are lucky that it has not, within the British main- stream, been necessary to create art with this moral status. But the British tendency either to dismiss this work, or to display it, patronisingly, as cultural or political arte- fact is an obscene perversion of some of the most difficult and meaningful artistic ges- tures of our time. The audience for such material in Germany, France, Italy, Scan- dinavia and America is growing steadily; Britain's isolationism is very much Bri- tain's own.

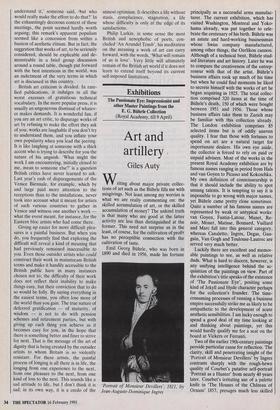

The excuse usually put forward in this country is that such 'outsider' work is too inaccessible for the general public. Of course the work is less accessible to the British public than is British art: that is what it means for something to be foreign. Paris is less accessible from London than is Tunbridge Wells. I recently served on a committee that was considering the purch- ase of works of art for a major museum in this country, and that dismissed the exam- ples of both Aids-related and non-First World art that were proposed on the grounds that it asked too much of a British public. It may be very interesting once you Ilya Kabakov's installation, 'He Lost his Mind, Undressed and Ran Away Naked', tells the story of an untalented painter, never permitted to exhibit his work, who lived in an overcrowded Moscow communal apartment and was therefore obliged to pile his indifferent pictures on one another until they left him no room to live, His own mediocrity, combined with the oppressiveness of communal life and the frustrations of trying to fight an overwhelming bureaucracy, drove him to abandon everything and run naked into the street. The installation shows the room he left behind, with all his notes, paintings and personal effects in the disorder in which they were deserted. The work comments on the nature of artistic activity, on the role of the artist and on the link between the oppressions of Soviet tyranny and inefficiency and the frustration of trying to retrieve some humanity from a brutal system. understand it,' someone said, -`-but who would really make the effort to do that?' In the exhaustingly decorous context of these meetings, the point seemed hardly worth arguing; this remark's apparent populism seemed like a concession from within a bastion of aesthetic elitism. But in fact, the suggestion that works of art, to be seriously considered, should be explicable and de- monstrable in a brief group discussion around a round table, though put forward with the best intentions in the world, was an indictment of the very terms in which art is discussed in this country.

British art criticism is divided. In rare- fied publications, it indulges in all the worst excesses of gratuitious technical vocabulary. In the more popular press, it is usually an ungenerous dismissal of whatev- er makes demands. It is wonderful fun, if you are an art critic, to disparage works of art by refusing to make the effort they ask of you; works are laughable if you don't try to understand them, and you inflate your own popularity when you lead the jeering. It is like laughing at someone with a thick accent who is trying to describe for you the nature of his anguish. 'What might the work I am encountering, initially closed to me, mean to someone else?' is a question British critics have never learned to ask. Last year's rash of disparagements of the Venice Biennale, for example, which by and large paid more attention to the receptions than to the installations, never took into account what it meant for artists of such various countries to gather in Venice and witness one another's work — what the event meant, for instance, for the Eastern bloc artists who had come there.

Giving up easier for more difficult plea- sures is a painful business. But when you do, you frequently find that exploring the difficult will reveal a kind of meaning that had previously remained inaccessible to you. Even those outsider artists who could construct their work in mainstream British terms and make it handily accessible to the British public have in many instances chosen not to; the difficulty of their work does not reflect their inability to make things easy, but their conviction that to do so would be folly. By saying everything in the easiest terms, you often lose more of the world than you gain. The true nature of deferred gratification — of maturity, of wisdom — is not to do with pension schemes and retirement parties, but with giving up each thing you achieve as it becomes easy for you, in the hope that there is something better and finer to strive for next. That is the message of the art of dignity that is being created by the outsider artists to whom Britain is so violently resistant. For these artists, the painful process of longing is all there is in life, the longing from one experience to the next, from one pleasure to the next, from one kind of loss to the next. This sounds like a sad attitude to life, but I don't think it is sad; in its own way, it is a credo of the utmost optimism. It describes a life without stasis, complacence, stagnation, a life whose difficulty is only at the edge of its satisfactions.

Philip Larkin, in some sense the most British and xenophobic of poets, con- cluded 'An Arundel Tomb', his meditation on the meaning a work of art can carry forward, with the words, 'What will remain of us is love'. Very little will ultimately remain of the British art world if it does not learn to extend itself beyond its current self-imposed limitations.

Previous page

Previous page