Exhibitions

The Passionate Eye: Impressionist and other Master Paintings from the E. G. Biihrle Collection (Royal Academy, till 9 April)

Art and artillery

Giles Auty

Writing about major private collec- tions of art such as the Biihrle fills me with misgivings. Not least among my worries is what we are really commenting on: the skilled accumulation of art, or the skilled accumulation of money? The unkind truth is that many who are good at the latter activity are less than distinguished at the former. This need not surprise us in the least, of course, for the cultivation of profit has no perceptible connection with the cultivation of taste.

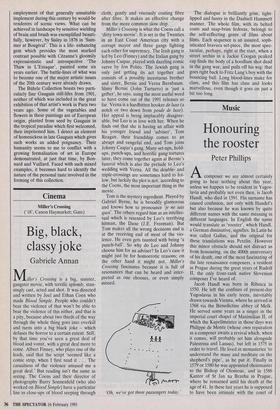

Emil Georg While, who was born in 1890 and died in 1956, made his fortune 'Portrait of Monsieur Devillers', 1811, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres principally as a successful arms manufac- turer. The current exhibition, which has visited Washington, Montreal and Yoko- hama already, was put together to cele- brate the centenary of his birth. Buhrle was an astute and hard-working businessman whose Swiss company manufactured, among other things, the Oerlikon cannon. Although of a technical bent, Bark stud- ied literature and art history. Later he was to compare the creativeness of the entrep- reneur with that of the artist. Biihrie's business affairs took up much of his time but when he could find moments he liked to secrete himself with the works of art he began acquiring in 1925. The total collec- tion comprised 320 items at the time of Biihrle's death, 150 of which were bought between 1951 and 1956. Those whose business affairs take them to Zurich may be familiar with this collection already. The London exhibition comprises 85 selected items but is of oddly uneven quality. I fear that those with fortunes to spend on art are a natural target for importunate dealers. His own eye aside, the collector is forced to rely on paid or unpaid advisers. Most of the works in the present Royal Academy exhibition are by famous names ranging in period from HaIs and van Goyen to Picasso and Kokoschka. My own definition of connoisseurship is that it should include the ability to spot unsung talents. It is tempting to say it is impossible to go wrong with major names, yet Biihrle came pretty close sometimes. Quite a number of his famous names are represented by weak or untypical works: van Goyen, Fantin-Latour, Manet, Re- noir, Monet, Matisse, Bonnard, Vuillard and Marc fall into this general category, whereas Canaletto, Ingres, Degas, Gau- guin, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec are served very much better.

Luckily there are excellent and memor- able paintings to see, as well as relative duds. What is hard to discern, however, is any unifying intelligence behind the ac- quisition of the paintings on view. Part of the exhibition's title speaks of the existence of 'The Passionate Eye', positing some kind of Jekyll and Hyde character perhaps for the collection's founder. The time- consuming processes of running a business empire successfully strike me as likely to be antipathetic to the development of acute aesthetic sensibilities. I am lucky enough to spend a good deal of my time looking at and thinking about paintings, yet this would hardly qualify me for a seat on the board at Vickers or Ferranti.

Two of the earlier 19th-century paintings provide particular cause for reflection. The clarity, skill and penetrating insight of the 'Portrait of Monsieur Devitiers' by Ingres contrasts sharply with the rough-hewn quality of Courbet's putative self-portrait 'Portrait as a Hunter' from nearly 40 years later. Courbet's irritating use of a palette knife in 'The Houses of the Château of Ornans' 1853, presages much less skilled employment of that generally unsuitable implement during this century by would-be renderers of scenic views. What can be achieved in landscape by sensitive wielding of brain and brush was exemplified beauti- fully, however, by Sisley in 1876 in 'Sum- mer at Bougival'. This is a life- enhancing gem which provides the most marked contrast possible with Cezanne's gloomily expressionistic and introspective 'The Thaw in L'Estaque, painted some six years earlier. The battle-lines of what was to become one of the major artistic issues of the 20th century were already drawn.

The Biihrle Collection boasts two parti- cularly fine Gauguin still-lifes from 1901, neither of which was included in the great exhibition of that artist's work in Paris two years ago. Some of the vegetables and flowers in these paintings are of European origin, planted from seed by Gauguin in the tropical paradise which first welcomed, then imprisoned him. I detect an element of homesickess in late Gauguin which gives such works an added poignancy. Their humanity seems to me to conflict with a growing formalisation of art in Europe demonstrated, at just that time, by Bon- nard and Vuillard. Faced with such mixed examples, it becomes hard to identify the nature of the personal taste involved in the forming of this collection.

Previous page

Previous page