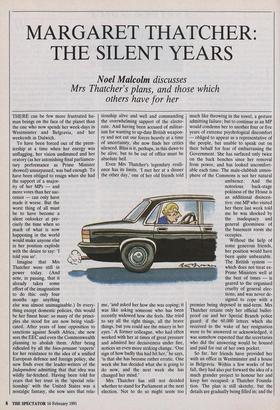

MARGARET THATCHER: THE SILENT YEARS

Noel Malcolm discusses

Mrs Thatcher's plans, and those which others have for her

THERE can be few more frustrated hu- man beings on the face of the planet than the one who now spends her week-days in Westminster and Belgravia, and her weekends in Dulwich.

Imagine that Mrs Thatcher were still in power today. (And note, in passing, that it already takes some effort of the imagination to do this: only four months ago anything else was almost unimaginable.) In every- thing except domestic policies, this would be her finest hour: so many of the princi- ples she stood for are now being vindi- cated. After years of lone opposition to sanctions against South Africa, she now sees the EEC and even the Commonwealth planning to abolish them. After being ridiculed by all the bien-pensant 'experts' for her resistance to the idea of a unified European defence and foreign policy, she now finds even the leader-writers of the Independent admitting that that idea was wildly far-fetched. Having been told for years that her trust in the 'special rela- tionship' with the United States was a nostalgic fantasy, she now sees that rela-

tionship alive and well and commanding the overwhelming support of the electo- rate. And having been accused of militar- ism for wanting to up-date British weapon- ry and not cut our forces heavily at a time of uncertainty, she now finds her critics silenced. Bliss is it, perhaps, in this dawn to be alive, but to be out of office must be absolute hell.

Even Mrs Thatcher's legendary resili- ence has its limits. 'I met her at a dinner the other day,' one of her old friends told me, 'and asked her how she was coping; it was like asking someone who has been recently widowed how she feels. She tried to say all the right things, all the brave things, but you could see the misery in her eyes.' A former colleague, who had often worked with her at times of great pressure and admired her decisiveness under fire, notices an even more striking change. 'One sign of how badly this had hit her,' he says, 'is that she has become rather erratic. One week she has decided what she is going to do now, and the next week she has changed her mind.'

Mrs Thatcher has still not decided whether to stand for Parliament at the next election. Not to do so might seem too much like throwing in the towel, a gesture admitting failure; but to continue as an MP would condemn her to another four or five years of extreme psychological discomfort — obliged to appear as a representative of the people, but unable to speak out on their behalf for fear of embarrassing the Government. She has surfaced only twice on the back benches since her removal from power, and has looked uncomfort- able each time. The male-clubbish atmos- phere of the Commons is not her natural ambience. And the notorious back-stage pokiness of the House is an additional disincen- tive: one MP who visited her there last week told me he was shocked by the inadequacy and general gloominess of the basement room she occupies.

So far, her friends have provided her with an office in Westminster and a house in Belgravia. Within a few weeks of her fall, they had also put forward the idea of a much grander project to honour her and keep her occupied: a Thatcher Founda- tion. The plan is still sketchy, but the details are gradually being filled in; and the more detailed those plans become, the more clear it is that the Thatcher Founda- tion, whatever else it does, will notbe the outlet for her political energies that Mrs Thatcher needs.

The title is both suggestive and mislead- ing. 'Thatcher Foundation' suggests one of those foundations for American ex- presidents, with a library, an archive of personal papers, a secretariat organising the ex-president's lecture-tours, and so on — altogether, a cross between a personal mausoleum and the private drive-in cathedral of a TV evangelist. The Thatcher Foundation will perform none of these fucntions. 'Of course she will take a close interest in it,' says Lord McAlpine, the former treasurer of the Conservative Party and the chief promoter of the Foundation, 'but it won't be organising her lecture-turs, and I don't see why it should have anything to do with storing her papers. I don't think it will even want to have a big building with a library. It will be a charitable foundation, devoted to education and research.' But would it be educating people in Thatcher- ite political principles? 'No, because it won't be a political body. It will be a charity, not a pressure-group. And it cer- tainly won't be a stalking-horse for any- body, or anything.' There are two obvious reasons for these vehement denials of political purpose. One reason can be found in paragraphs 51 to 56 of the Report of the Charity Commission- ers for 1981, which set out the guidelines on political activities by charitable bodies. The main guidelines here seems to be: 'Don't'. Paragraph 51 will remind the Thatcher Foundation trustees of what hap- pened when the Bonar Law Memorial Trust fell foul of the Inland Revenue in 1933; the principle established by that case was that 'A trust for the education of the public in one particular set of political principles is not charitable.' Paragraph 54 seems even more severe: 'Charities must avoid . . . seeking to influence or remedy those causes of poverty which lie in the social, economic and political structures of countries and communities . . . [or] seek- ing to eliminate social, economic, political or other injustice.' So a charity can educate East Europeans in the principles of the free market, in the way that one might educate them in the principles of Greek philology; but it had better not mention that following those economic principles might make the listeners less poor or more free. These guidelines manage to be very strict without being very exact; and we can be sure that, with the draft proposals for the Thatcher Foundation coming before the Charity Commissioners next week, Lord McAl- pine's lawyers have been studying them carefully.

The other reason for circumspection is even more obvious. A politically active Thatcher Foundation would be like an unexplosed bomb ticking away on the doorstep of the Conservative Party. It could never put forward any radical policy proposals (of the sort which the Adam Smith Institute or the Centre for Policy Studies produce almost every week) with- out a great cry going up in the media abnout a Thatcherite opposition to John Major within the Tory Party. In a sense, the most important reason for making the Foundation a charity is not the tax advan- tages this brings, but the public guarantee that it offers of non-interference in the orindary political life of the Conservative Party. And this in turn offers a safeguard to the Party's finances, because it means that fund-raising for the Foundation will 'I'm worried, by this age we should've seen a careers officer.' not or at least should not overlap with fund-raising for the Party.

So what will the Foundation actually do? Even the original letter which was sent out to potential trustees was not very specific. But the main emphasis will clearly be on large-scale international issues: East-West relations, democracy, free trade, the en- vironment. There will be conferences and international scholarships; there will be research projects and publications, some of them conducted in-house and published by the Foundation itself, and others (probably the majority) commissioned from outside bodies such as universities and policy institutes. The board of trustees so far includes Lord McAlpine, Lord Harris of High Cross (the economist, Ralph Harris), Lord Gowrie (who was one of the first people to offer support to Mrs Thatcher after her fall, and whose job at Christies must put him in touch with a usefully large number of millionaires), Professor Ken- neth Monogue (LSE), Professor Norman Stone (Oxford and the Sunday Times) and Daphne Park (former diplomat, BBC gov- ernor and Principal of Somerville); one or two Ameicans, and perhaps a bishop, are also being added to the list.

It will all be so very respectable: a gathering of the great and the good, who will help organise conferences at which more great and good people willmeet to talk about general issues, without — perish the thought — taking a Thatcherite line on anything. Three of the trustees, as it happens, are on the board of the anti- federalist Bruges Group (Harris, Minogue, Stone); but it will be much, much harder for the Thatcher Foundation to say or do anything in support of the policies laid out on Mrs Thatcher's Bruges speech. One begins to sense a problem here: if rich benefactors want to do something special for Mrs Thatcher, why should they fund something which will have to fall over backwards not to seem to be expressing her political principles?

This raises a further and even bigger problem. Mrs Thatcher's instincts on fore- ign policy have usually been right — as recent events are helping to prove. But in following those instincts, she had always to battle against the consensus of the foreign affairs Establishment in this country: an Establishment made up of the Foreign Office, the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House, St Antony's College at Oxford, the discussion groups at Ditchley Park and the Koenigswinter con- ferences. It is a powerful consensus, all the more strong for being woven out of person- al connections rather than formal, institu- tional ones. Its political character is liberal- centrist; in the late 1970s it was keen on detente and 'round table' meetings with Communist apparatchiks, and in the late 1980s it was (and still is) keen on European federalism. Apart from the excellent but small-scale Institute for European Defence and Strategic Studies, there is not a single institute in this country with a distinctively Conservative or right-wing approach to foreign policy — an extraordinary fact, when one thinks of the dominance of right-wing think-tanks in the field of domestic policy.

In theory, this yawning gap could be filled by the Thatcher Foundation. In practice, it will not. The Charity Commis- sioners, or, failing them, the new resident at No. 10, will see to that. As for Mrs Thatcher herself, she need not remain politically silent for ever (she is planning an important speech for the end of this month); but each time she tackles any controversial topic, she will attract a huge amount of publicity, some of it damaging to herself and to her party. The issue of yielding British sovereignty to Brussels is the one issue on which she will never be silenced; and strategists at Conservative Central Office are already mentioning this as one reason for calling an early general election, before the results of the Inter- Governmental Conferences may have forced her to speak out. But otherwise she is left to conduct a lonely battle with her conscience over when and where to speak the truths she believes in. In all this, she will get little help from the Thatcher Foundation. It may be her monument, but can never be her mouthpiece.

Previous page

Previous page