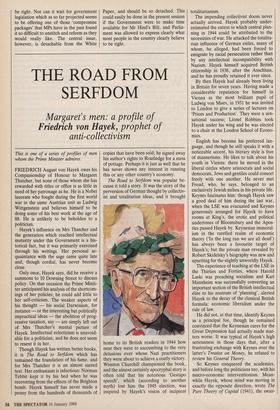

THE ROAD FROM SERFDOM

Margaret's men: a profile of

Friedrich von Hayek, prophet of

anti-collectivism

This is one of a series of profiles of men whom the Prime Minister admires.

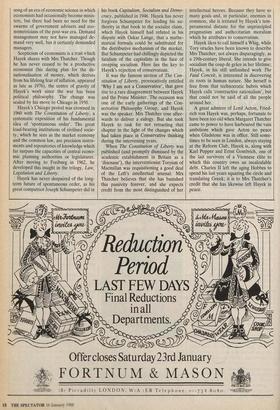

FRIED RICH August von Hayek owes his Companionship of Honour to Margaret Thatcher, but none of those whom she has rewarded with titles or office is as little in need of her patronage as he. He is a Nobel laureate who fought during the first world war in the same Austrian unit as Ludwig Wittgenstein and believes himself to be doing some of his best work at the age of 88. He is unlikely to be beholden to a politician.

Hayek's influence on Mrs Thatcher and the generation which reached intellectual maturity under this Government is a his- torical fact, but it was primarily exercised through his writings. Her personal ac- quaintance with the sage came quite late and, though cordial, has never become close.

Only once, Hayek says, did he receive a summons to 10 Downing Street to discuss policy. On that occasion the Prime Minis- ter anticipated his analysis of the shortcom- ings of her policies; he could add little to her self-criticism. The weaker aspects of his thought — his social Darwinism, for instance — or the interesting but politically impractical ideas — the abolition of prog- ressive taxation, say — are simply left out of Mrs Thatcher's mental picture of Hayek. Intellectual eclecticism is unavoid- able for a politician, and he does not seem to resent it in her.

Though Hayek has written better books, it is The Road to Serfdom which has remained the foundation of his fame, and for Mrs Thatcher it is an almost sacred text. Her enthusiasm is infectious: Norman Tebbit kept it by his bed when he was recovering from the effects of the Brighton bomb. Hayek himself has never made a penny from the hundreds of thousands of copies that have been sold; he signed away his author's rights to Routledge for a mess of pottage. Perhaps it is just as well that he has never shown any interest in running this or any other country's economy.

The Road to Serfdom was popular be- cause it told a story. It was the story of the perversion of German thought by collectiv- ist and totalitarian ideas, and it brought home to its British readers in 1944 how near they were to succumbing to the very delusions over whose Nazi practitioners they were about to achieve a costly victory. Winston Churchill championed the book, and the almost certainly apocryphal story is often told that his notorious 'Gestapo speech', which (according to another myth) lost him the 1945 election, was inspired by Hayek's vision of incipient totalitarianism.

The impending collectivist doom never actually arrived. Hayek probably under- estimated the extent to which central plan- ning in 1944 could be attributed to the necessities of war. He attacked the totalita- rian influence of German exiles, many of whom, he alleged, had been forced to emigrate by racial persecution rather than by any intellectual incompatibility with Nazism. Hayek himself acquired British citizenship in 1938, after the Anschluss, and he has proudly retained it ever since.

By then Hayek had already been living in Britain for seven years. Having made a considerable reputation for himself in Vienna as the most brilliant pupil of Ludwig von Mises, in 1931 he was invited to London to give a series of lectures on 'Prices and Production'. They were a sen- sational success; Lionel Robbins took Hayek under his wing and he was elected to a chair at the London School of Econo- mics.

English has become his preferred lan- guage, and though he still speaks it with a noticeable accent, his literary style is free of mannerisms. He likes to talk about his youth in Vienna: there he moved in the liberal circles where aristocrats and social democrats, Jews and gentiles could consort freely with one another. He never met Freud, who, he says, belonged to an exclusively Jewish milieu in his private life. Keynes fascinates him: though Hayek saw a good deal of him during the last war, when the LSE was evacuated and Keynes generously arranged for Hayek to have rooms at King's, the erotic and political undertones of Bloomsbury and the Apos- tles passed Hayek by. Keynesian immoral- ism in the rarefied realm of economic theory (In the long run we are all dead') has always been a favourite target of Hayek's; but the private man revealed by Robert Skidelsky's biography was new and upsetting for the slightly unworldly Hayek.

The experience of teaching at the LSE in the Thirties and Forties, where Harold Laski was preaching socialism and Karl Mannheim was successfully converting an important section of the British intellectual elite to his nostrum of 'planning', alerted Hayek to the decay of the classical British formula: economic liberalism under the rule of law.

He did not, at that time, identify Keynes as a principal foe, though he remained convinced that the Keynesian cures for the Great Depression had actually made mat- ters worse. It was typical of Hayek's high seriousness in those days that, after a frustrating exchange with Keynes over the latter's Treatise on Money, he refused to review his General Theory.

So Keynes conquered the academics, and before long the politicians too, with his macro-economic interventionism. Mean- while Hayek, whose mind was moving in exactly the opposite direction, wrote The Pure Theory of Capital (1941), the swan- song of an era of economic science in which economists had occasionally become minis- ters, but there had been no need for the swarms of government advisers and eco- nometricians of the post-war era. Demand management may not have managed de- mand very well, but it certainly demanded managers.

Scepticism of economists is a trait which Hayek shares with Mrs Thatcher. Though he has never ceased to be a productive economist (his daring plan for the de- nationalisation of money, which derives from his lifelong fear of inflation, appeared as late as 1976), the centre of gravity of Hayek's work since the war has been political philosophy. The change was sealed by his move to Chicago in 1950.

Hayek's Chicago period was crowned in 1960 with The Constitution of Liberty, a systematic exposition of his fundamental idea of 'spontaneous order'. The great load-bearing institutions of civilised socie- ty, which he sees as the market economy and the common law, are precision instru- ments and repositories of knowledge which far surpass the capacities of central econo- mic planning authorities or legislatures. After moving to Freiburg in 1962, he developed this insight in the trilogy, Law, Legislation and Liberty.

Hayek has never despaired of the long- term future of spontaneous order, as his great compatriot Joseph Schumpeter did in

his book Capitalism, Socialism and Demo- cracy, published in 1946. Hayek has never forgiven Schumpeter for lending his au- thority in that book to the socialist claim, which Hayek himself had refuted in his dispute with Oskar Lange, that a mathe- matical formula could be substituted for the distributive mechanism of the market. But Schumpeter had chillingly depicted the fatalism of the capitalists in the face of creeping socialism. Here lies the key to Hayek's rejection of conservatism.

It was the famous section of The Con- stitution of Liberty, provocatively entitled 'Why I am not a Conservative', that gave rise to a rare disagreement between Hayek and the Prime Minister. The occasion was one of the early gatherings of the Con- servative Philosophy Group, and Hayek was the speaker. Mrs Thatcher rose after- wards to deliver a eulogy. But she took Hayek to task for not retracting that chapter in the light of the changes which had taken place in Conservative thinking during the intervening years.

When The Constitution of Liberty was published (and promptly dismissed by the academic establishment in Britain as a 'dinosaur), the interventionist Toryism of Macmillan was requisitioning a good deal of the Left's intellectual arsenal. Mrs Thatcher believes that she has banished this passivity forever, and she expects credit from the most distinguished of her

intellectual heroes. Because they have so many goals and, in particular, enemies in common, she is irritated by Hayek's tem- peramental distaste for the unprincipled pragmatism and authoritarian moralism which he attributes to conservatism.

Hayek likes to call himself a Whig, while Tory oracles have been known to describe Mrs Thatcher, not always disparagingly, as a 19th-century liberal. She intends to give socialism the coup de grace in her lifetime; Hayek, in his still unfinished work The Fatal Conceit, is interested in discovering its roots in human nature. She herself is free from that technocratic hubris which Hayek calls 'constructive rationalism', but that could not be said of all the people around her.

A great admirer of Lord Acton, Fried- rich von Hayek was, perhaps, fortunate to have been too old when Margaret Thatcher came to power to have harboured the vain ambitions which gave Acton no peace when Gladstone was in office. Still some- times to be seen in London, always staying at the Reform Club, Hayek is, along with Karl Popper and Ernst Gombrich, one of the last survivors of a Viennese elite to which this country owes an incalculable debt. Charles II left the aging Hobbes to spend his last years squaring the circle and translating Greek; it is to Mrs Thatcher's credit that she has likewise left Hayek in peace.

Previous page

Previous page