Sale-rooms

Old master bargains?

Peter Watson explains the current price discrepancy between old masters and Impressionists

The market in old master paintings is dying. This report of a death is, of course, exaggerated, a touch of chiaroscuro, for effect. But not greatly. Slip into Green's champagne bar, or Wilton's, or any other West End watering hole and you will find the Barons of Bond Street telling each other that old masters — especially gold ground Sienese pictures — are bargains these days, mere snips, in marked contrast to the swatch of second-rate Impressionists which are flooding the market and are as outrageously priced as the turbot they have just been munching. It may well be true that the landscapes and views of Henri Martin, Henri Lebas- que and Henri Le Sidanier are as uniformly similar as their first names suggest, but that isn't the point. The point is that the old masters on offer these days aren't any better. In fact, they are a good deal worse. The sale-room season which has just finished underlined this more vividly than ever before. The difference between the Impressionist sales and the old masters (between the worlds of new money and old connoisseurship) was as sharp as that between Rubens and Red Adair.

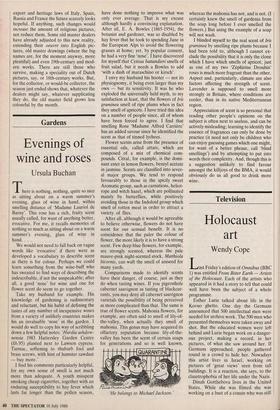

Consider this table which shows the value of 1,001 pictures sold at Christie's and Sotheby's in London in the past three weeks:

Below £25,000 Above £25,000 27 per cent 73 per cent 73 per cent 27 per cent

The art market isn't cricket and there is no Wisden of the salerooms for those of us who love statistics and would wish to compare recent trends with what happened in years gone by. But the absolute symmet- ry of these figures highlights the stark message. They might be interpreted as showing that old masters are a bargain but a closer scrutiny of the sales will not support that. For the figures also reveal the much more important fact that no fewer than 49 per cent of old masters at the sales were valued at between £1,000 and £10,000. That compares with just three per cent of the Impressionist and modern pictures.

It is not immediately apparent who these

Impressionists Old masters

`bargain basement' old masters will appeal to. Any number of examples could be given, but how about 'A Landscape with Classical Ruins and Figures near a Foun- tain', by a follower of Cornelis van Poelen- burgh, which was valued at £1,500-2,000 at Sotheby's but failed to sell? Or 'The Interior of a Brothel', by the Circle of Frans Xavier Hendrick Verbeeck, which also failed to fetch its expected £3,000- 4,000? Or 'Abigail Supplicating Before David', by the circle of Luigi Garzi, which sold for £1,600?

Several London old master dealers are kept in business by the museums of the world, of middle America especially. But these are not pictures they would be interested in. They are nowhere near museum quality. Nor would many private individuals find such pictures especially rewarding. Such paintings occupy no iden- tifiable place in the scheme of things: they are simply not good enough to help form 'a collection'. Nor, in most cases, would they repay study or research. No amount of knowledge about these artists is going to make the paintings any better. And yet this quality of painting comprises half the market.

In truth, the dominance of this £1,000- £10,000 price bracket in the old master field reflects the fact that the supply of decent paintings has dried up to the point where it is now critical. This season the most illustrious names were Tintoretto, Rubens, Canaletto, Ricci, Crivelli and Rosa. There were only four first-class old master names with more than one picture represented at the sales (Rubens, van Ruysdael and Canaletto, with two each, and Rosa, who had four). Contrast that with the Impressionist and modern sales where there were 14 Picassos, nine Utril- los, eight Legers and Van Dongens, six Bonnards, five Degas and the inevitable dozen or so Renoirs.

Tastes do change in the art world and there have been a few occasions in the past when old masters outstripped contempor- ary works, most notably after the great Orleans sale in 1798 and again towards the end of the last century. But the paintings on offer then were in quality much, much better than 95 per cent of what is on the market now. Another complicating factor is that a third of the old masters in the salerooms are religious images which seem unlikely ever to regain the popularity and appeal they once may have had. This season, the proportion of old masters fetching less than the estimate, or being bought in, was significantly higher than for Impressionist and modern pictures, and the rates for religious pictures were higher still.

Unless the quality of old masters on the market improves, therefore, the idea that there are 'bargains' to be found in this field is something of an illusion. And, since the only way that more good old masters could become available would be a change in the export and heritage laws of Italy, Spain, Russia and France the future scarcely looks hopeful. If anything, such changes would increase the amount of religious pictures, not reduce them. Some old master dealers have already adjusted to this new reality, extending their oeuvre into English pic- tures, old master drawings (where the big names are, for the moment anyway, more plentiful) and even 19th-century and mod- ern works. There are still those who survive, making a speciality out of Dutch pictures, say, or 18th-century works. But, for the collector, or would-be collector, the season just ended shows that, whatever the dealers might say, whatever supplicating they do, the old master field grows less colourful by the month.

Previous page

Previous page