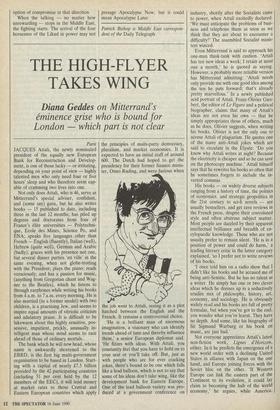

THE HIGH-FLYER TAKES WING

Diana Geddes on Mitterrand's

eminence grise who is bound for London — which part is not clear

Paris JACQUES Attali, the newly nominated president of the equally new European Bank for Reconstruction and Develop- ment, is one of those lucky — or irritating, depending on your point of view — highly talented men who only need four or five hours' sleep and who therefore seem cap- able of cramming two lives into one.

Not only does Attali, who is 46, serve as Mitterrand's special adviser, confidant, and (some say) guru, but he also writes books — 15 published to date, including three in the last 12 months; has piled up degrees and doctorates from four of France's elite universities — Polytechni- que, Ecole des Mines, Science Po, and ENA; speaks five languages other than French — English (fluently), Italian (well), Hebrew (quite well), German and Arabic (badly); graces with his presence not one, but several dinner parties 'en ville' in the same evening, when not globe-trotting with the President; plays the piano; reads voraciously; and has a passion for music, (anything from Gregorian chant and Wag- ner to the Beatles), which he listens to through earphones while writing his books from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m. every morning. He is also married (to a former model) with two children, is a practising Jew, and seems to inspire equal amounts of vitriolic criticism and adulatory praise. It is difficult to be lukewarm about this highly sensitive, pos- sessive, impatient, prickly, unusually in- telligent man whose mind seems to race ahead of those of ordinary mortals.

The bank which he will now head, whose name is awkwardly shortened to the EBRD, is the first big multi-government organisation to be based in London. Start- ing with a capital of nearly £7.5 billion provided by the 42 participating countries (including 51 per cent held by the 12 members of the EEC), it will lend money at market rates to those Central and Eastern European countries which apply the principles of multi-party democracy, pluralism, and market economies. It is expected to have an initial staff of around 600. The Dutch had hoped to get the presidency for their former finance minis- ter, Onno Ruding, and were furious when the job went to Attali, seeing it as a plot hatched between the English and the French. It remains a controversial choice.

`He is a brilliant man of enormous imagination, a visionary who can identify trends ahead of time and thereby influence them,' a senior European diplomat said. `He fizzes with ideas. With Attali, you constantly feel that you have to hold on to your seat or you'll take off. But, just as with people who are for ever cracking jokes, there's bound to be one which falls like a lead balloon, which is not to say that some of his ideas don't take wing, like the development bank for Eastern Europe. One of the lead balloon variety was pro- duced at a government conference on industry, shortly after the Socialists came to power, when Attali excitedly declared: `We must anticipate the problems of busi- ness and telephone them as soon as we think that they are about to encounter a difficulty!' The assembled Socialist minis- ters winced.

Even Mitterrand is said to approach his one-man think-tank with caution. 'Anal' has ten new ideas a week; I retain at most one a month,' he is quoted as saying. However, a probably more reliable version has Mitterrand admitting: `Attali needs only provide me with one good idea among the ten he puts forward; that's already pretty marvellous.' In a newly published acid portrait of Attali, Franz-Olivier Gies- bert, the editor of Le Figaro and a political biographer, claims that many of Attali's ideas are not even his own — that he simply appropriates those of others, much as he does, Olivier suggests, when writing his books. Olivier is not the only one to accuse Attali of plagiarism. He quotes one of the many anti-Attali jokes which are said to circulate in the Elysee: 'Do you know why Attali writes at night? Because the electricity is cheaper and so he can save on the photocopy machine.' Attali himself says that he rewrites his books so often that he sometimes forgets to include the in- verted commas.

His books — on widely diverse subjects ranging from a history of time, the politics of economics and strategic geopolitics in the 21st century to sci-fi novels — are usually bestsellers, and get rave reviews in the French press, despite their convoluted style and often abstruse subject matter. Most people are dazzled by their apparent intellectual brilliance and breadth of en- cylopaedic knowledge. Those who are not usually prefer to remain silent. 'He is in a position of power and could do harm,' a leading literary critic in the latter category explained, 'so I prefer not to write reviews of his books.

`I once told him on a radio show that I didn't like his books and he accused me of being anti-Semitic. But he has no talent as a writer. He simply has one or two clever ideas which he dresses up in a seductively erudite mix of philosophy, history, art, economy, and sociology. He is obviously widely read and his books are full of pretty formulas, but when you've got to the end, you wonder what you've learnt. They have no depth. And some, like his biography of Sir Sigmund Warburg or his book on music, are just bad.'

Not everyone appreciates Attali's latest non-fiction work, Lignes d'Horizon, either. In it he predicts the emergence of a new world order with a declining United States in alliance with Japan on the one hand, and Europe joining forces with the Soviet bloc on the other. 'If Western Europe can link the eastern part of the Continent to its evolution, it could lay claim to becoming the hub of the world economy,' he argues, while America, undermined by debt, drugs, speculation, urban decay and a crumbling manufactur- ing base, could find itself increasingly subservient to Japan and relegated to the role of the Pacific region breadbasket. 'I'm not saying that it will happen, but if, like me, you believe that industry remains the only durable base for a country's power, the signs of a relative American decline are convergent and irrefutable,' he says.

`It's just wacky!' an outraged American political scientist declared. 'He's been way off beam before. He was predicting in the mid-Seventies that Germany would no longer be a great power in 15 years' time, for example, and only a couple of weeks before the collapse of the Berlin Wall he was assuring everyone that the reunifica- tion of Germany was not on the immediate cards. He strikes me as a lightweight. There's less to him than meets the eye. People are amazed that he can do all the things he does, but maybe he doesn't do any of them very well.'

Nevertheless, Mitterrand, who is no fool, has thought well enough of Attali to keep him as his chief adviser and 'emi- nence grise' for the past nine years, getting him to prepare the world economic sum- mits, act as his emissary on delicate mis- sions abroad, sit in on Cabinet 'and top- secret defence council meetings, attend to tete-a-tete talks with foreign heads of state, and, of course, produce a constant flow of new ideas. Anyone visiting Mitterrand, including the Prime Minister, is obliged to go through Attali's office, which adjoins the President's. All memos to the Presi- dent are first filtered by Attali. He is one of the favoured few to have the right to an (at least) daily meeting with the President, and to play golf with him. Better than anyone else, he knows what the President is doing. In 1983, when Mitterrand decided to make a secret impromptu visit to Beirut after the bombing of the French army barracks in the city with the loss of 58 French soldiers' lives, Attali (according to Le Monde) was the only one who knew, and even had to refuse to tell Pierre Mauroy, the Prime Minister, when he rang anxiously at mid- night to find out where the President had gone.

Attali is said to be fiercely jealous of his undoubtedly exceptional relationship with Mitterrand. The two men hold each other in mutual esteem, trust and affection. Yet it is difficult to judge how much real power Attali has. Certainly in the early days, when Attali first joined Mitterrand as his economic adviser in 1973, at a time when Mitterrand knew next to nothing about money, Attali, with his impressive array of degrees, was highly successful in getting his blend of Marxist-Keynesian economic poli- cies adopted by the Socialist leader. Since then, his influence has waxed and waned at different times. But Mitterrand has always been a man who likes to take his final decisions alone, and is not one to be easily manipulated. Franz-Olivier Giesbert sug- gests that Attali wants to leave the Ely's& because he has fallen from grace, but perhaps, after 17 years together, both men feel it is time for a change.

Is he suited to his new job? He certainly has the right contacts (he claims to be on first-name terms with 47 heads of state or government), the intelligence, and the imagination, but he has no management experience and negligible banking experi- ence, unlike his calmer, gentler, but less brilliant identical twin brother, Bernard, who after completing ENA (like Jacques) followed a traditional high-flying civil ser- vant's career, climbing up through the ranks of various public banks, insurance companies and other institutions, before beng appointed head of Air France in 1988.

Born in 1943 in Algiers, where their father, a self-made man from a poor Jewish family, succeeded in building up a flourishing perfume business, the two boys came with their parents to France at the height of the Algerian civil war in 1956, and were immediately sent to the presti- gious Janson-de-Sailly lye& in the fashion- able 16th arrondissement of Paris. Jacques, the older and more ambitious of the two, set his eyes on the Ecole Polytechnique, and got in, while Bernard contented him- self with the law faculty at the Sorbonne. After spending the whole of the Sixties notching up degrees, Jacques joined the Conseil d'Etat (in order to give himself time to write) and took up university teaching before joining Mitterrand's staff in 1973, where he has remained ever since.

The development bank was Attali's idea; he wanted the job of president and Mitter- rand, who always likes to reward his loyal servants, did his utmost to get it for him, despite the row it caused among some of the other bank members, notably the Dutch. 'He was far from an obvious choice,' a European diplomat involved in setting up the bank confessed.

Attali has already announced that he will leave the Elysee to take up his new post when the bank starts operating in around six to nine months' time. However, he is said to be resolutely opposed to the prop- osed Dockland site for the bank, preferring a more prestigious site in the City. He is due to arrive in London next week for talks with British government officials and is understood to have expressed an interest in the New Change building, opposite St Paul's. However, the rental there is likely to be double that at the Treasury's prefer- red site in Canary Wharf, on the Isle of Dogs. Including rates, the difference in cost between the two sites could be as much as £3 million a year, according to British government officials, requiring a much larger subsidy for the bank than the Government originally 'bargained for. Treasury officials are said to be about to try to convince Attali of the merits of a Dockland site by offering him a private aircraft for his personal use at City Air- port. The high-flying Attali would doubt- less expect nothing less.

Previous page

Previous page