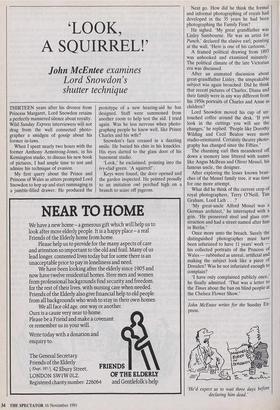

'LOOK, A SQUIRREL!'

John McEntee examines

Lord Snowdon's shutter technique

THIRTEEN years after his divorce from Princess Margaret, Lord Snowdon retains a perfectly mannered silence about royalty. Wild Sunday Express interviewers will not drag from the well connected photo- grapher a smidgen of gossip about his former in-laws.

When I spent nearly two hours with the former Anthony Armstrong-Jones, in his Kensington studio, to discuss his new book of pictures, I had ample time to test and admire his technique of evasion.

My first query about the Prince and Princess of Wales as sitters prompted Lord Snowdon to hop up and start rummaging in a jumble-filled drawer. He produced the prototype of a new hearing-aid he has designed. Staff were summoned from another room to help test the aid. I tried again. Was he less nervous when photo- graphing people he knew well, like Prince Charles and his wife?

Snowdon's face creased in a dazzling smile. He buried his chin in his knuckles. His eyes darted to the glass door of his basement studio.

'Look,' he exclaimed, pointing into the ivy-clad green. 'A squirrel!'.

Keys were found, the door opened and the garden inspected. He pointed proudly to an imitation owl perched high on a branch to scare off pigeons. Next go. How did he think the formal and informal photographing of royals had developed in the 35 years he had been photographing the Family Firm?

He sighed. 'My great grandfather was Linley Sambourne. He was an artist for Punch,' declared the elusive earl, pointing at the wall. 'Here is one of his cartoons.'

A framed political drawing from 1893 was unhooked and examined minutely. The political climate of the late Victorian era was discussed.

After an animated discussion about great-grandfather Linley, the unspeakable subject was again broached. Did he think that recent pictures of Charles, Diana and their family were in any way different from his 1950s portraits of Charles and Anne as children?

Lord Snowdon moved his cup of un- touched coffee around the desk. 'If you look in the cuttings you will see the changes,' he replied. 'People like Dorothy Wilding and Cecil Beaton were more studio-orientated. Certainly theatre photo- graphy has changed since the Fifties.'

The charming earl then meandered off down a memory lane littered with names like Angus McBean and Oliver Messel, his famous uncle, the designer.

After exploring the lesser known bran- ches of the Messel family tree, it was time for one more attempt.

What did he think of the current crop of royal photographers, Terry O'Neill, Tim Graham, Lord Lich . . .?

'My great-uncle Alfred Messel was a German architect,' he interrupted with a grin. 'He pioneered steel and glass con- struction and had a street named after him in Berlin.'

Once more unto the breach. Surely the distinguished photographer must have been infuriated to have 11 years' work — his collected portraits of the Princess of Wales — rubbished as unreal, artificial and making the subject look like a piece of Dresden? Was he not infuriated enough to complain?

'I have only complained publicly once,' he finally admitted. 'That was a letter to the Times about the ban on blind people at the Chelsea Flower Show.'

'He'd expect us to wait three days before declaring him dead.'

Previous page

Previous page