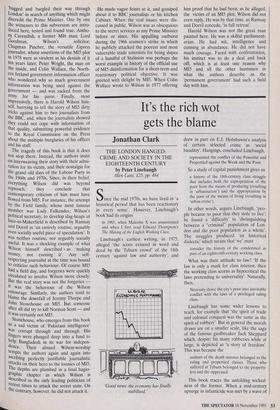

A wronged man • need not be a good man

Paul Foot

SMEAR! WILSON AND THE SECRET STATE by Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay Fourth Estate, £20, pp.390 Anyone who wants to know how the British secret service works owes a huge debt to Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay. Working from Ramsay's modest home in Hull, without any of the cuttings libraries or research facilities available to main- stream journalists, they edit Lobster, an occasional and indispensable magazine which probes the most fascinating political questions of all. Why are things not as they seem? Why are so many political stories inexplicable in terms of genuine political interest or conflict? Their answer is 'the secret state' or what is more normally (and absurdly) known as 'the intelligence services'. Since both authors — Ramsay very closely, Dorril I think less so — are attached to the Labour Party they start at the subversion of British Labour. They tell 'us that for every penny of Moscow gold which went into the Labour Party, thousands of pounds were invested by United States Intelligence. Until Hugh Gaitskell died in 1963, the CIA was content to ensure, through front organisations like the Ariel Foundation and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, that Labour leaders continued to be user friendly. When Gaitskell died, the scene changed. The new elected leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson, was no longer a pushover for the CIA. He had been associated with Aneurin Bevan, had attacked US policy in South East Asia, and was therefore plainly a communist stooge. To prove the point, it could be shown that he had a soft spot for Russia and had even been there, The attitude of the 'intelligence' community was best summed up by the remark of the MIS buffoon Peter Wright: 'No one should be Prime Minister who has been twelve times to Moscow'.

The great brains of the CIA and MI5 were so deranged by the death of their man Gaitskell that they assumed the Russians killed him. Many top agents went to their graves certain in this knowledge, though every single medical opinion they commis- sioned ruled it quite impossible. They determined to do their utmost to discom- fort the chief beneficiary of this impossible poisoning: Harold Wilson. Anyone with any lingering doubts that a gang of MI5 officers concentrated their enormous and terrifying powers to this objective should read this book. The evidence is marshalled carefully, and builds up to an unanswerable indictment.

The campaign started long before Peter Wright says it did. There was much more than is generally conceded, for instance, to the Cecil King plot to unseat Wilson and replace him with a 'national government' in 1968. King himself, even while chairman of the Mirror group of newspapers, worked closely with MI5. Though he became Prime Minister in 1964, Wilson was not even told of the deal that same year whereby Antho- ny Blunt was promised immunity from prosecution in exchange for help about for- mer spies. Labour Ministers, including a Lord Chancellor, Lord Gardiner, were not allowed to see their own MIS files. Junior Ministers, even right-wing ones like John Diamond or Neil MacDermot, were followed and smeared — MacDermot was driven out of office by MIS because his wife was born in a communist country. MIS hysteria about another Junior Minister, Bernard Floud, probably led to his suicide and certainly led to that of his friend Phoebe Pool, who flung herself under a train.

All this was the prelude to the orgy of dirty tricks which followed the election of the third and fourth Labour governments under Harold Wilson in February and October 1974. Forgery and burglary were the two specialities of the Peter Wright gang, which, in Wright's memorable phrase

'bugged and burgled their way through London' in search of anything which might discredit the Prime Minister. One by one the witnesses to this subversion are intro- duced here, tested and found true: Antho- ny Cavendish, a former MI6 man; Lord Goodman, Wilson's solicitor; Chapman Pincher, the versatile Express Journalist, whose assertions of the MIS plot in 1978 were as virulent as his denials of it ten years later; Peter Wright, the man on the inside, and Cohn Wallace, the North- ern Ireland government information officer who wondered why so much government information was being used against the government — and was sacked from the army for his pains. Finally, most impressively, there is Harold Wilson him- self, hurrying to tell the story of MI5 dirty tricks against him to two journalists from the BBC, and, when the journalists showed they could not cope with information of that quality, submitting powerful evidence to the Royal Commission on the Press about the multiple burglaries of his offices and his staff.

The tragedy of this book is that it does not stop there. Instead, the authors insist on interweaving their story with their admi- ration for its victim, and their nostalgia for the grand old days of the Labour Party in the 1960s and 1970s. Since, in their belief, everything Wilson did was beyond

reproach, they conclude that Contemporary criticism of him must have flowed from M15. For instance, the attempt by the Field farinily, whose most famous member was Lady Falkender, Wilson's Political secretary, to develop slag-heaps at Ince-in-Makerfield is described by Ramsay and Dorril as 'an entirely routine, arguably even socially useful piece of speculation'. It was neither routine, nor arguably socially useful. It was a shocking example of what Wilson himself described • as 'making money, not earning it'. Any self- respecting journalist at the time was bound to criticise such behaviour. Of course MI5 had a field day, and forgeries were quickly circulated to involve Wilson more closely. B. ut the real story was not the forgeries — it was the behaviour of the Wilson entourage. Similarly, the authors tend to blame the downfall of Jeremy Thorpe and John Stonehouse on MI5. But someone after all did try to kill Norman Scott — and It was certainly not MI5.

Stonehouse, who emerges from this book as a sad victim of 'Pakistani intelligence' Was corrupt through and through. His fingers were plunged deep into a fund to help, Bangladesh in its war for indepen- dence. Their absurd Wilson-worship tempts the authors again and again into ascribing perfectly justifiable journalistic attacks on their hero to the loonies of MI5. The depths are plumbed in a final hagio- graphic chapter in which Wilson is described as the only leading politician of recent times to attack the secret state. On the contrary, however, he did not attack it. He made vague feints at it, and gossiped about it to BBC journalists or his kitchen Cabinet. When the real issues were dis- cussed in public, Wilson was as obsequious to the secret services as any Prime Minister before or since. His appalling outburst during the 1966 seamen's strike in which he publicly attacked the poorest and most vulnerable trade unionists for being dupes of a handful of Stalinists was perhaps the worst example in history of the official use of MI5 disinformation for a short-term and reactionary political objective. It was greeted with delight by MI5. When Colin Wallace wrote to Wilson in 1977 offering him proof that he had been, as he alleged, the victim of an MI5 plot, Wilson did not even reply. He was by that time, as Ramsay and Dorril concede, 'in full retreat'.

Harold Wilson was not the great man painted here. He was a skilful parliament- arian. He had wit, intelligence and cunning in abundance. He did not have much courage. Faced with confrontation, his instinct was to do a deal and back off; which is at least one reason why MIS and all the other huntsmen in what the authors describe as the 'permanent government' had such a field day with him.

Previous page

Previous page