NEW YORK'S NEW MAN

on the black who would be mayor

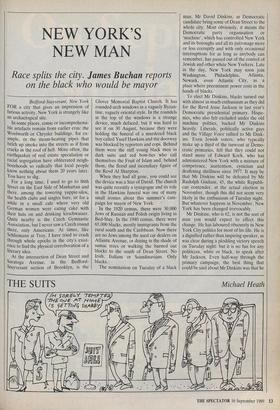

Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York FOR a city that gives an impression of furious activity, New York is strangely like an archaelogical site.

In some places, comic or incomprehensi- ble artefacts remain from earlier eras: the Woolworth or Chrysler buildings, for ex- ample, or the steam-heating pipes that belch up smoke into the streets as if from cracks in the roof of hell. More often, the earthquakes of real estate speculation or racial segregation have obliterated neigh- bourhoods so radically that local people know nothing about them 20 years later. You have to dig.

For a long time, I used to go to 86th Street on the East Side of Manhattan and there, among the towering yuppie-silos, the health clubs and singles bars, sit for a While in a small cafe where very old German women were eating cake with their hats on and drinking kirschwasser. Quite nearby is the Czech Gymnastic Association, butt never saw a Czech round there, only Americans. At times, like Schliemann at Troy, I have tried to crash through whole epochs in the city's exist- ence to find the physical corroboration of a literary idea.

At the intersection of Dean Street and Saratoga Avenue, in the Bedford- Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, is the Glover Memorial Baptist Church. It has rounded-arch windows in a vaguely Byzan- tine, vaguely oriental style. In the roundels at the top of the windows is a strange device, much defaced, but it was hard to see it on 30 August, because they were holding the funeral of a murdered black boy called Yusef Hawkins and the doorway was blocked by reporters and cops. Behind them were the stiff young black men in dark suits and red bow-ties who call themselves the Fruit of Islam and, behind them, the florid and incendiary figure of the Revd Al Sharpton.

When they had all gone, you could see the device was a Star of David. The church was quite recently a synagogue and its role in the Hawkins funeral was one of many small ironies about this summer's cam- paign for mayor of New York.

In the 1920 census, there were 30,000 Jews of Russian and Polish origin living in Bed-Stuy. In the 1940 census, there were 65,000 blacks, mostly immigrants from the rural south and the Caribbean. Now there are no Jews among the used car dealers on Atlantic Avenue, or dozing in the shade of sumac trees or walking the burned out blocks to the south of Dean Street. No Irish, Italians or Scandinavians. Only blacks.

The nomination on Tuesday of a black man, Mr David Dinkins, as Democratic candidate bring some of Dean Street to the whole city. Most obviously, it means the Democratic party organisation or 'machine', which has controlled New York and its boroughs and all its patronage more or less corruptly and with only occasional interruptions for as long as anybody can remember, has passed out of the control of Jewish and other white New Yorkers. Late in the day, New York may soon join Washington, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Newark, even Atlantic City, as a place where preeminent power rests in the hands of blacks.

To elect Mr Dinkins, blacks turned out with almost as much enthusiasm as they did for the Revd Jesse Jackson in last year's Democratic presidential primary. Hispa- nics, who also felt excluded under the old machine politics, backed Mr Dinkins heavily. Liberals, politically active gays and the Village Voice rallied to Mr Dink- ins. Even Jewish voters, who typically make up a third of the turn-out at Demo- cratic primaries, felt that they could not stand more of Edward Koch, who has administered New York with a mixture of competence, inattention, cynicism and deafening shrillness since 1977. It may be that Mr Dinkins will be defeated by Mr Rudolph Giuliani, 45, the white Republi- can contender, at the actual election in November, though this did not seem very likely in the enthusiasm of Tuesday night. But whatever happens in November, New York has been changed irrevocably.

Mr Dinkins, who is 62, is not the sort of man you would expect to effect this change. He has laboured obscurely in New York City politics for most of his life. He is a dignified rather than inspiring speaker, as was clear during a plodding victory speech on Tuesday night: but it is no fun for any politician, white or black, to speak after Mr Jackson. Even half-way through the primary campaign, the best thing that could he said about Mr Dinkins was that he had made few enemies.

The murder of Yusef Hawkins stood the campaign on its head. On the night of 23 August, Hawkins, who was just 16, went to see a used car to buy in Bensonhurst, a tight-knit Italian neighbourhood in south- ern Brooklyn. He was set upon by a group of local young men and shot dead. For the next week, tension ran high in Brooklyn. Mr Sharpton and others led marches of protest into Bensonhurst. At the funeral on Dean Street, it seemed that Mr Spike Lee's Bed-Stuy film, Do the Right Thing, had become reality and the supposedly real world simply a commentary on it: some- body in the Dean Street crowd waved a placard saying BOYCOTT PIZZA MAFIA PIGFOOD.

At that point, many people in New York (including this one) thought the primary would split on racial lines. There seemed more than a possibility that the corrosive insecurities of the beleaguered working- class white neighbourhoods of Ben- sonhurst or Howard Beach would be echoed in Manhattan and in the white sections of Queens and Staten Island. Mr Koch, 64, who in the early summer was a by-word for all that was wrong with New York, the crime, the corruption, the drugs and overloaded hospitals and demoralised schools, suddenly seemed a contender.

This was quite wrong. It does seem that Democrats, at least, are not only fed up with the cynicism of the Koch administra- tion. They are truly worried that the city is being split up into warring neighbourhoods and are willing to back a man who can make peace between them. 'Remember me,' Mr Dinkins said in his victory speech, 'I'm the guy who brings people together. You voted your hopes but not your fears and, in so doing, you said something pro- found about this town. Tonight, the people are ahead of the experts.'

Back in Bed-Stuy, in the 1920s, the singer Lena Home grew up in her grandpa- rents' house on Chauncey Street. Across the street were some poor Irish who 'were supposed to be the less privileged people of the neighbourhood', as she wrote in her memoirs. Down the block was a Scandina- vian family she was told she must always be polite to. Up to last Tuesday, this seemed an impossibly innocent and distant world, well and truly buried. Perhaps David Dink- ins will bring it back.

James Buchan is the New York correspon- dent of the Financial Times -

Previous page

Previous page