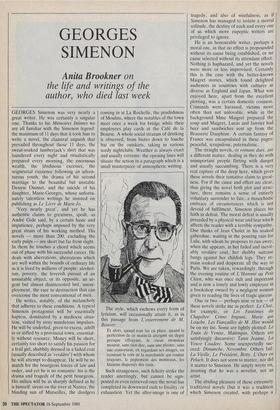

GEORGES SIMENON

Anita Brookner on

the life and writings of the author, who died last week

GEORGES Simenon was very nearly a great writer. He was certainly a singular one. Thanks to his Memoires Intimes we are all familiar with the Simenon legend: the maximum of 11 days that it took him to write a novel, the claustral anguish that prevailed throughout those 11 days, the sweat-soaked lumberjack's shirt that was laundered every night and ritualistically prepared every morning, the enormous wealth, the libidinous excesses, the seigneurial existence following an adven- turous youth, the drama of his second marriage to the beautiful but unstable Denyse Ouimet, and the suicide of his daughter, Marie-Georges, whose unfortu- nately talentless writings he insisted on publishing as Le Livre de Marie-Jo.

'Very nearly great', and yet he has authentic claims to greatness, spoilt, as Andre Gide said, by a certain haste and impatience, perhaps imposed by the very great strain of his working method. His novels — more than 200, excluding the early pulps — are short but far from slight. In them he touches a chord which seems out of phase with his successful career. He deals with aberrations, aberrations which are well within the bounds of ordinary life as it is lived by millions of people: alcohol- ism, poverty, the feverish pursuit of an unsuitable object, or its opposite, an ur- gent but almost disinterested lust, unem- ployment, the race to destruction that can overcome the most conventional of men.

He writes, notably, of the melancholy that adheres to these conditions. A typical Simenon protagonist will be essentially hapless, dominated by a mediocre situa- tion, visited by stray murderous impulses. He will be underfed, given to excess, adrift in or stifled by a provincial town, essential- ly without resource. Money will be short, certainly too short to satisfy his passion for a frail girl, shabbily dressed in a faded coat (usually described as `vercldtre") with whom he will attempt to disappear. He will be no match for the bourgeois forces of law and order, and yet he is no romantic: his is the drama and tragedy of the petit bourgeois. His milieu will be as sharply defined as he is himself: sirens on the river at Nantes, the blinding sun of Marseilles, the dredgers coming in at La Rochelle, the prudishness of Moulins, where the notables of the town meet once a week for bridge while their employees play cards at the Cafe de la Bourse. A whole social stratum of drinking is observed, from bistro down to louche bar on the outskirts, taking in various seedy nightclubs. Weather is always exact and usually extreme: the opening lines will situate the action in a paragraph which is a small masterpiece of atmospheric writing.

The style, which eschews every form of lyricism, will occasionally attain it, as in this passage from L'enterrement de M. Bouvet:

Et alors, quand tout fut en place, quand la perfection de ce matin-la atteignit un degre presque cffrayant, le vieux monsieur mourut, sans rien dire, sans une plainte, sans une contorsion, en regardant ses images, en ecoutant la voix de la marchande qui coulait touj ours, le pepiement des moineaux, les klaxons disperses des taxis.

Such strangeness, such felicity strike the reader unerringly, but cannot be sign- posted or even retrieved once the novel has completed its downward rush to finality, or exhaustion. Yet the after-image is one of tragedy, and also of wistfulness, as if Simenon has managed to isolate a mortal solitude, the destiny of each and every one of us which more eupeptic writers are privileged to ignore.

He is an honourable writer, perhaps a moral one, in that no effect is propounded without its cause being established, or no cause selected without its attendant effect. Nothing is haphazard, and yet the novels were more or less improvised. Certainly this is the case with the better-known Maigret stories, which found delighted audiences in countries with cultures as diverse as England and Japan. What was enjoyed here, apart from the excellent plotting, was a certain domestic cosiness. Criminals were harassed, victims more often than not unlovable, while in the background Mme Maigret prepared the soup and Maigret, Lucas and Janvier had beer and sandwiches sent up from the Brasserie Dauphine. A certain fantasy of France was encapsulated in these pages: peaceful, scrupulous, paternalistic.

The straight novels, or romans durs, are a different matter, dealing as they do with unimportant people flirting with danger and usually succumbing. There is a very real rapture of the deep here, which gives these novels their tentative claim to great- ness. For if the cause and effect are clear, thus giving the novel both plot and struc- ture, there remains a sense of entirely voluntary surrender to fate, a masochistic embrace of circumstances which is not devoid of fulfilment. Simenon places his faith in defeat. The moral defeat is usually preceded by a physical wear and tear which affects the reader with a terrible sympathy. One thinks of Jean Cholet in his soaked gaberdine, waiting in the pouring rain for Lulu, with whom he proposes to run away; when she appears, in her faded and inevit- ably verchltre coat, her shabby suitcase bangs against her childish legs. They re- main soaked and desperate all the way to Paris. We are taken, rewardingly, through the evening routine of L'Homme au Petit Chien, who was once rich and important and is now a lonely and lowly employee in a bookshop owned by a negligent woman given to reading the lives of tragic queens. One or two — perhaps nine or ten — of these novels strike me as perfect. Le Chat, for example, or Les FantOrnes du Chapelier: Crime Impuni, Marie qui Louche, Les Fiangailles de M. Hire would be on my list. Some are tightly plotted: Le Train de Venise, Malempin. Others are satisfyingly discursive: Tante Jeanne, La Veuve Couderc. Some unexpectedly suc- ceed: Dimanche, Novembre. Others fail: La Vieille, Le President, Betty, L'Ours en Peluch. It does not seem to matter, nor did it matter to Simenon. He simply wrote on, insisting that he was a novelist, not an artist.

The abiding pleasure of these extremely traditional novels (but it was a tradition which Simenon created, with perhaps a nod to Balzac) casts in doubt all post- modern attempts to interfere with a strictly linear treatment and a system in which the author can be called upon to honour his contract with the reader. Serious readers — artisanal readers, in the same way that Simenon was an artisanal writer — recog- nize him as one of their own.

And all the time that he was writing his four or five novels a year he was building houses for his family, buying cars, checking into clinics for major or minor disorders, containing the madness of his wife and daughter, being unfailingly courteous to journalists, and insisting on his own humil- ity, which was in fact genuine. No man who could write so unswervingly about the feeble and the dispossessed could have been anything else.

His latter years were peaceful, but it was a peace erected on the ruins of a great sorrow. He visited his daughter's ashes, which were scattered in a corner of his garden, every day, and every day dictated letters to her. His companion, Teresa, had been his wife's maid. She was faithful, silent, submissive, and one is tempted to think of her as Mme Maigret, were it not for some of the details set down unselfcon- sciously in the Memoires Intimes. In his distant youth — he was 86 when he died — he had been a choirboy in Liege, his home town. As a writer he remained rigorous and obedient, whatever the divagations of his private life. Very nearly great? Perhaps something more. He created a world, and few contemporary writers have managed to do as much.

Previous page

Previous page