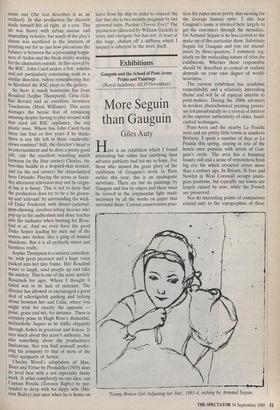

Exhibitions

Gauguin and the School of Pont-Aven: Prints and Paintings (Royal Academy, till 19 November)

More Seguin than Gauguin

Giles Auty

Here is an exhibition which I found interesting but rather less satisfying than advance publicity had led me to hope. For those who missed the great glory of the exhibition of Gauguin's work in Paris earlier this year, this is an inadequate substitute. There are but six paintings by Gauguin and few by others and these must be viewed in the crepuscular light made necessary by all the works on paper that surround them. Correct conservation prac-

tices for paper mean pretty dim viewing for the average human optic. I also fear Gauguin's name is invoked here largely to get the customers through the turnstiles, for Armand Seguin is no less central to the make-up of this particular show. Substitute Seguin for Gauguin and you cut attend- ances by three-quarters; I comment reg- ularly on the misleading nature of titles for exhibitions. Whether those responsible should be described as cynical or realistic depends on your own degree of world- weariness.

The current exhibition has academic respectability and a relatively interesting theme and will be of especial interest to print-makers. During the 1880s advances in modern photochemical printing proces- ses led paradoxically to a revival of interest in the superior authenticity of older, hand- crafted techniques.

Pont-Aven and the nearby Le Pouldu were and are pretty little towns in southern Brittany. I spent a number of days at Le Pouldu this spring, staying in one of the hotels once popular with artists of Gau- guin's circle. The area has a haunting beauty still.and a sense of remoteness from big city life which attracted artists more than a century ago. In Britain, St Ives and Newlyn in West Cornwall occupy analo- gous positions, but typically our towns are largely ruined by now, while the French are preserved.

Nor do interesting points of comparison extend only to the topographies of these 'Young Breton Girl Adjusting her Hat', 1893-4, etching by Armand Seguin remote Celtic strongholds. Synthetism, in which Gauguin was prime mover, was perhaps the first truly modern movement in that it shifted emphasis forever from the Splendours of the outer world to the supposed wonders of the inner. As the catalogue explains: 'It must not be forgot- ten that the aesthetic questions these artists found most intriguing were primarily ab- stract. Their concerns were line, colour, rhythm and harmony, and their subjects were chosen for the ability to best allow the exploration of these non-objective ideas.' One strand in the gradual intellectualisa- tion of art, together with growing disin- terest in the seen, dates from this precise period, almost exactly a century ago. Synthetism involved a flattening of space, via the influence of Japanese prints — and an emphasis on the rhythmic use of line and colour. Why artists needed to travel to Brittany to produce an art of the mind is a question raised even more strongly nearly 70 years later by the choice of St Ives as the epicentre for post-war British abstraction. Again, the more theoretical the art, the greater the degree of bickering and rivalry. Emile Bernard's historic rift with Gauguin was to be echoed umpteen times over during the heyday of St Ives abstraction.

Gauguin and the School of Pont-Aven is a celebration less of a beautiful area than of the convoluted artistic theories of a small group who once lived there; like so much in the lifespan of modernism the interest of the art here is often merely historical rather than visual. Print-making was not necessarily an ideal vehicle for the Principles of synthetism. Indeed, Gauguin himself was not especially accomplished in the medium — at this stage at least — and many of his disciples were to show rene- gade tendencies, even sampling such for- bidden fruits as recessive space, atmos- phere and light, as in Seguin's `L'Entree de la Riviere'. Robert Bevan and Roderic O'Conor produced telling images in their own freely adapted versions of synthetist practice. Both were first-class artists but I cannot agree with the merits the exhibition catalogue proposes for such as Henri De- lavalide or Maxime Maufra. Their prints may be very rare but scarcity is not a yard- stick of anything. Looking through the exhibition cata- logue, I find myself intrigued by the entry for Roderic O'Conor's 'Le Soir'. The authoritative catalogue note tells us why a mass in the left-hand distance is an in- vented hill, whereas I would read it instant- ly as a credible cloud. If I am wrong this would not be a unique confusion. Some time ago I approached the Cisa pass in Italy for the first time at dusk, with only 40 miles of a long drive to Lerici to complete. Ahead of me I admired what I took to be a steepling cloud mass, licked by the last glimmers of a dying sun. Hours later I had Passed at last over the top of the 'cloud', in dense fog. The flickerings of light I had seen were the headlights of vast lorries.

Previous page

Previous page