THE BEACH EMBRACE

John Ralston Saul on the problems of unclothed greetings

St Tropez IT HAS become increasingly common over the last decade to see women on beaches wearing a single postage stamp, which used to be limited to the professional stage under the name of the `G-string'. Some- times they wear nothing at all. As for men, most of them conceal their parts within what is called a bikini, which consists of one half the material needed to make a narrow tie, narrow ties being in fashion this year. Some do not hide at all. All of this, on the basis of what I see, is to be applauded in the name of gravity (Newton's law of) if nothing else. The average human, when fully dressed, is able to disguise a good part of his or her physical imperfections, but once the pro- tective layers are peeled off the flaws appear. The effect of an old-fashioned bathing suit, which covered much of the body with one layer of constricting mate- rial, was to, emphasise these flaws; elastic and stretch nylon have a cruel way of drawing attention to protruding stomachs, cellulite, flabby backsides and sagging or uneven brests. What this means is that the more perfect the body, the better it looks covered up.

Today's flowering of visible flesh on the beach has created the sort of unexpected myth that belongs in the category of the big joke. Nudity, it would seem, is the result of increased blindness and not of a relaxation in the details of daily prudery., Put another way, no matter what is standing before you on the sand, you must act as if the world is as it has always been.

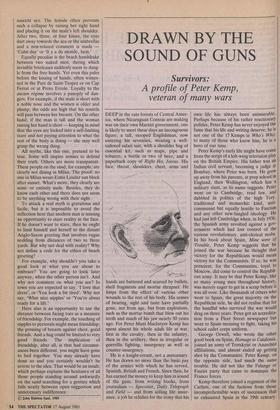

A perfect example of this is the social embrace. All across the beaches of Europe in the months of July and August, from Marbella with its rich Moors reconquering Spain, through the cheap-holiday-makers of the various Costas to out beyond St Tropez where the golden sands of Tahiti and Pampelonne are covered by the flaccid glitz of Parisians who can't swim but lie in neat, tight rows, and on past the sweating, dusty suburbanites at St Maxime and the swollen-bellied property developers at Cannes and Nice to the neat little social packages of Italians eating and smoking and talking on the sand north and south of Porto Ercole, and further south the large- breasted, black-haired, black-suited Morn- mas on the other side of Rome . . . on and on through the Greek islands covered by ephemeral Vikings with their sturdier, interesting women or by assorted flocks of homosexuals or lesbians, each dominating their rocks. . . everywhere, everywhere you will find people greeting each other with the standard social embraces, as if they were arriving at a Paris dinner or an opera in Milan: two kisses for the middle classes and above; three for the lower- middle; four for the working class. All of this, however, is complicated by the risk of direct skin contact.

A greeting, which in town usually in- volves a hug and some show of affection, is suddenly transformed into a spectacle of tortured acrobatics. Last week, on a sec- luded beach, I saw men and women approach each other with a smile of friendship. Their eyes met; in fact, their eyes locked as if they were trying to stare each other down. To allow the gaze to wander would have been lewd. The bodies halted at a distance one from the other that varied anywhere between 50 centimetres and one metre. Both sets of feet were spread to the side in search of greater balance. Backsides were arched to the rear to avoid any contact of pubic hair. If both embraces were integrally nude, this arch risked throwing out the spine. The shoul- ders were then squared and stretched back to avoid loose and uncontrollable breasts from touching mail pectorals, firm or slack. Finally, the necks were bent forward into a hunchbacked position and each body curved towards the other from the point of the unmoving toes until a pair of lips touched a cheek.

At such an angle, the chances of actually falling over are high and when this hap- pens, the result is a tangle of naked, horizontal bodies writhing with a confusion which can be mistaken for the groping of nascent sex. The female often prevents such a collapse by raising her right hand and placing it on the male's left shoulder. After two, three, or four kisses, the eyes dart away towards the sea or the umbrellas and a non-related comment is made 'Calm day' or '11 y a du monde, hein.'

Equally peculiar is the beach handshake between two naked men, during which invisible briefcases suddenly seem to dang- le from the free hands. Yet even this pales before the kissing of hands, often witnes- sed in the Parc de Saint-Tropez or on Cap

Ferrat or at Prato Ercole. Loyalty to the ancien regime involves a panoply of dan-

gers. For example, if the male is short with a noble nose and the women is older and plump, the odds are high that his nostrils will pass between her breasts. On the other hand, if the man is tall and the woman raising her hand is short — keeping in mind that the eyes are locked into a self-limiting stare and not paying attention to what the rest of the body is doing — she may well grasp the wrong thing.

All myths, like this one, pretend to be true. Some will inspire armies to defend their truth. Others are more transparent.

These people on the sand, for example, are clearly not dining in Milan. The proof: no one in Milan wears Estee Lauder sun block after sunset. What's more, they clearly are semi- or entirely nude. Besides, they do know each other and there does not seem to be anything wrong with their sight.

To attack a real myth is gratuitous and facile, but it is impossible to avoid the reflection here that modern man is missing an opportunity to stare reality in the face. If he doesn't want to stare, then he ought to limit himself and herself to the distant Anglo-Saxon greeting that involves vague nodding from distances of two to three yards. But why not deal with reality? Why not define a code for the ethics of beach greeting?

For example, why shouldn't you take a good look at what you are about to embrace? You are going to look later anyway, when the other person isn't. And why not comment on what you see? In town you are expected to say, 'I love that dress', or 'You look a bit tired'. Why not say, 'What nice nipples' or 'You're about ready for a lift.'

Here also is an opportunity to use the distance between facing toes as a measure of friendship. For example, the touching of nipples to pectorals might mean friendship; the pressing of breasts against chest, good friends. And a hug could be limited to very good friends. The implication of friendship, after all, is that had circumst- ances been different, you might have gone to bed together. You may already have done so and you certainly wouldn't be averse to the idea. That would be an insult; which perhaps explains the hesitancy of all those people standing around awkwardly on the sand searching for a gesture which falls neatly between open suggestion and unnecessary indifference.

© John Ralston Saul, 1985

Previous page

Previous page