ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Alberto Giacometti (Scottish National Gallery of Art, Edinburgh, till 22 Sept, then at the Royal Academy, London, from 9 Oct till 1 Jan)

Giacometti's vision of reality

Martin Gayford

In 1945 the artist Alberto Giacometti had a disconcerting experience in a cinema in Montparnasse. Instead of reality, sud- denly on the screen he saw merely monochrome patterns. The figures, `becoming black and white blobs, that's to say they were losing all meaning, and instead of looking at the screen I kept looking at my neighbours, who were becoming something altogether unknown'. Around him, at this time, he started to see not so many ordinary mid-century Parisians, but 'heads in the void ... some- thing alive and dead simultaneously'. 'I cried out in terror as if I had just crossed a threshold, as if I were entering a world never before seen'. Everywhere was an 'unbelievable sort of silence', 'the world was light, light'.

Most of us, I suppose, if challenged, would probably say that the world around us looks a little like a moving colour photo- graph. But perhaps we just don't look hard enough, or long enough. Giacometti's vision of the world as a place fathomlessly weird and mysterious — as in fact perhaps it truly is — recharged his vocation as an artist. 'At that moment I suddenly felt the need to paint, to make sculpture, because photography had never given me a funda- mental vision of reality.'

For Giacometti the effort to transmit what he really saw — which had begun long before the vision in the cinema entailed a life of awesome arduousness. He worked all day and every day, sometimes all through the night too, with utter con- tempt for comfort and health. From the mid Thirties until his death in 1966, he inhabited the same tiny, spartan Parisian studio — without hot water or lavatory (except for part of the war, which he spent in equally confined quarters in a cheap hotel in Geneva). As he lay dying, he remarked that he must be going mad as he had lost the impulse to work.

What he did through those endless hours, working sometimes from memory and sometimes from life, was enormously repetitive. He painted, drew and sculpted, for example, his brother Diego countless thousands of times. The point being that to get just one head right, any head, or even part of a head like a nose, the way he really saw it, would be a triumph. But that was exactly what he knew was impossible, which in turn was what made it obsessively inter- esting.

The result of this intense struggle, or a substantial chunk of it, is on view in the large exhibition currently at the Scottish National Gallery of Art. In aggregate the effect is not so much repetitive, however, as of a slow, uneven increase in intensity. Giacometti, who set himself a task of such difficulty, naturally possessed the gift of easy virtuosity. His easy, youthful assimila- tion of a series of styles from post-Impres- sionism to Cubism was interrupted by a compulsion to show things the way he real- ly saw them. As a teenager he had found himself, when drawing some pears, forced to make them tiny — that is the size they were in his visual field, not the size he knew them to be (hold up two fingers in front of your eyes, and measure some of the things you can see, and you will under- stand what Giacometti meant).

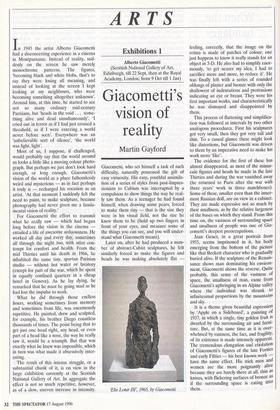

Later on, after he had produced a num- ber of abstract-Cubist sculptures, he felt similarly forced to make the figures and heads he was making absolutely flat — Elie Lotar 111; 1965, by Giacometti feeling, correctly, that the image on the retina is made of patches of colour; one just happens to know it really stands for an object in 3-D. He also had to simplify enor- mously, `to get nearer my idea, I had to sacrifice more and more, to reduce it'. He was finally left with a series of rounded oblongs of plaster and bronze with only the shallowest of indentations and protrusions indicating an eye or breast. They were his first important works, and characteristically he was dismayed and disappointed by them.

This process of flattening and simplifica- tion was followed at intervals by two other analogous procedures. First his sculptures got very small, then they got very tall and thin. To a casual glance these might look like distortions, but Giacometti was driven to them by an imperative need to make his work more 'like'.

The evidence for the first of these has almost disappeared, as most of the minus- cule figures and heads he made in the late Thirties and during the war vanished away (he returned to Paris after the war with three years' work in three matchboxes). Some of these, smaller even than the inner- most Russian doll, are on view in a cabinet. They are made expressive not so much by their smallness, as by the relative largeness of the bases on which they stand. From this time on, the vastness of surrounding space and smallness of people was one of Gia- cometti's deepest preoccupations.

Jean Genet, in a great portrait from 1955, seems imprisoned in it, his body emerging from the bottom of the picture like that Beckett character who is gradually buried alive. If the sculpture of the Renais- sance shows man dominating his environ- ment, Giacometti shows the reverse. Quite probably, this sense of the vastness of space, the smallness of man, came from Giacometti's upbringing in an Alpine valley where the individual was shrunk to infinitesimal proportions by the mountains and sky.

It is a theme given beautiful expression by 'Apple on a Sideboard', a painting of 1937, in which a single, tiny golden fruit is dwarfed by the surrounding air and furni- ture. But, at the same time as it is over- whelmed by vastness, the fact, and fragility, of its existence is made intensely apparent. The tremendous elongation and etiolation of Giacometti's figures of the late Forties and early Fifties — his best known work have the same effect. His stick men and women are the more poignantly alive because they are barely there at all, thin as knives, with flickering surfaces of bronze as if the surrounding space is eating into them. The women, always standing, motionless, arms at sides, are remote like goddesses or idols. And there one comes to a part of Giacometti's art that has less to do with perception than obsession. Like Cezanne — an artist with a similar dogged quest to transmit his sensations of reality into art inside Giacometti was a seething mass of psycho-sexual tension and violence. Domi- nated by a powerful mother, plagued by Impotence, fascinated by prostitution, his feelings towards women were a complex mixture of aggression, frustration and ado- ration.

These were given most direct expression during his Surrealist period, a sort of artis- tic holiday from the slog of depicting appearances. As a Surrealist, Giacometti found creation blissfully easy rather than agonisingly difficult. Ideas simply came to him, he claimed, fully finished, and he exe- cuted them — creating neat models of desire unsatisfied and anger expressed. Some, the 'Disagreeable Objects' for exam- ple, look like executive toys of insidiously nasty intent. The 'Woman with her Throat Cut' looks like a crushed scorpion. A simi- lar psychological background lies behind bizarre works such as the chariot — an inaccessible goddess parading in triumph en a huge pair of wheels. But then, of course, the peculiarity of the outer world is Partly a reflection of the turmoil of the inner — another reason why the camera cannot tell the profounder truths.

Previous page

Previous page