Exhibitions 2

Views of war

Gavin Stamp

War can inspire, or generate, great art. The Imperial War Museum surely houses one of the finest and most repre- sentative collections of 20th-century Brit- ish art in the country. This was because during the Great War the authorities had the imagination to commission many of the best contemporary painters to cover the conflict and carnage, and the desolation of the Western Front seems to have pro- foundly affected them. Similarly, the ghastly task of burying the dead brought out the best in the architects commissioned by the Imperial War Graves Commission. In the second world war, although the moral cause was clearer than in the first, the resulting art on the whole seems to me to be of a lesser intensity and quality, although the populist nature of the conflict resulted in many fine works in the realist tradition.

Clearly the Falklands War cannot be compared with either world war. As the conflict was to be measured in weeks rather than years, it is remarkable that it generated any art at all. The only artist who was officially commissioned — at very short notice — to accompany the Task Force to the other side of the globe was Linda Kitson. Other painters merely illus- trated aspects of the war after the event, or expressed a political comment about the whole nature of the expedition.

Although it would seem unlikely, both because of the nature of the conflict and because of the artistic climate of the 1980s, that the Falklands War could generate art of the intensity and poignancy of the Great War, I must say at once that I cannot comment on the artistic merit of Linda Kitson's drawings and other art works now on display at the Manchester City Art Gallery. With that concern for the general public and that respect for culture so long associated with the British trade union movement, the National Union of Public Employees chose the occasion of the open- ing of the Falklands Factor exhibition to go on strike and barricade Charles Barry's two noble buildings, so preventing me and many others from entering. The dispute, I may say, was not with Mrs Thatcher, nor was it a protest against her wicked im- perialist exercise in neo-militarism; it was with Manchester City Council (Labour) and concerned such matters as grading and the iniquity of museum security staff occa- sionally being asked to help the curators in the moving of heavy objects.

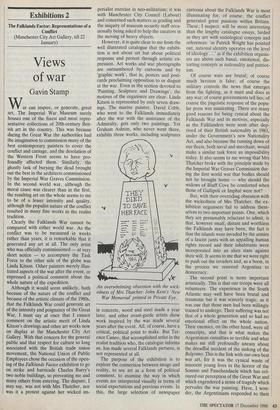

However, it is quite clear to me from the well illustrated catalogue that the exhibi- tion is not about art but about political response and protest through artistic ex- pression. Art works and war photographs are outnumbered by cartoons and by 'graphic work', that is, posters and post- cards proclaiming opposition to or disgust at the war. Even in the section devoted to 'Painting, Sculpture and Drawings', the motives of the organisers are clear. Linda Kitson is represented by only seven draw- ings. The marine painter, David Cobb, who went to the Falklands immediately after the war with the assistance of the Admiralty, gets only two paintings. Yet Graham Ashton, who never went there, exhibits three works, including sculptures An overwhelming obsession with the wick- edness of Mrs Thatcher: John Kent's 'New War Memorial' printed in Private Eye.

in concrete, wood and steel made a year later, and other avant-garde artists show work inspired by the war made several years after the event. All, of course, have a critical, political point to make. But Ter- ence Cuneo, that accomplished artist in the realist tradition who, the catalogue informs us, has made several Falklands pictures, is not represented at all.

The purpose of the exhibition is to explore the connection between image and reality, to see art as a form of political comment, to examine the way in which events are interpreted visually in terms of social expectations and previous events. In this, the large selection of newspaper cartoons about the Falklands War is most illuminating for, of course, the conflict generated great passions within Britain. These, I suspect, will be more interesting than the lengthy catalogue essays, larded as they are with sociological concepts and references: 'as Patrick Wright has pointed out, national identity operates on the level of ideology ...' as if the exhibition organis- ers are above such banal, emotional, dis- torting concepts as nationality and patriot- ism.

Of course wars are brutal; of course much heroism is false; of course the military controls the news that emerges from the fighting, as it must and does in any war; of course governments tell lies; of course the jingoistic response of the popu- lar press was nauseating. There are many good reasons for being cynical about the Falklands War and its motives, especially as the Falklanders were soon after dep- rived of their British nationality in 1983, under the Government's new Nationality Act, and also because the running down of our fleets, both naval and merchant, would make a similar task force an impossibility today. It also seems to me wrong that Mrs Thatcher broke with the principle made by the Imperial War Graves Commission dur- ing the first world war that bodies should not be brought home — why should the widows of Bluff Cove be comforted when those of Gallipoli or Imphal were not?

But, with their overriding obsession with the wickedness of Mrs Thatcher, the ex- hibition organisers fail to address them- selves to two important points. One, which they are presumably reluctant to admit, is that, however small, distant and worthless the Falklands may have been, the fact is that the islands were invaded by the armies of a fascist junta with an appalling human rights record and their inhabitants were incorporated into an alien state against their will. It seems to me that we were right to push out the invaders and, as a boon, in the process we restored Argentina to democracy.

The second point is more important artistically. This is that our troops were all volunteers. The experience in the South Atlantic may well have been brutal and traumatic but it was scarcely tragic, as it was one that those men had been willingly trained to undergo. Their suffering was not that of a whole generation and so had no emotional effect on the whole nation. Their enemies, on the other hand, were all conscripts, and that is what makes the Argentinian casualties so terrible and what makes me still profoundly uneasy about the dreadful incident of the sinking of the Belgrano. This is the link with our own best war art, for it was the cynical waste of innocent young lives in the horror of the Somme and Passchendaele which has col- oured our perception of the Great War and which engendered a sense of tragedy which pervades the war painting. Have, I won- der, the Argentinians responded to their disaster in Las Malvinas with any art which expresses the cynical waste of lives, the suffering, the awfulness and the stupidity of war? I do not know. All we have in this exhibition is one anti-Thatcher magazine cover from an 'Argentinian satirical maga- zine'. This seems to me a lost opportunity.

Previous page

Previous page