BRENDAN

By BRIAN BEHAN

Ah death where is thy sting a Iing a ling. —The Hostage, by Brendan Behan.

WHAT do I think of Brendan Behan?' The lorry driver looked worried for a minute. 'Oh, [know, the big fat Irishman that was always getting drunk on telly. Well, he's a lad, isn't he?'

Was this all there was to brother Brendan? Was he just the poor man's drunken Beatle? The crown prince of the never-ending booze- UP? The press wrote big headlines that said nothing. The biggest thing about their stories was their complete lack of knowledge about Brendan. Why did he kill himself, a man who loved life? Loved to swim, play Rugby football and, above all, read. Hidden behind a waterfall Of beer was a man who could no longer live in a world where all the things he had fought for came to nothing. A disappointed man. Yes, dis- appointed in the failure of the republican movement. Disappointed in the collapse of the left-wing world that looked upon Stalin as our father and Russia as our Mecca.

For my brother was first and foremost a rebel. He really fought for the things he believed in. And that made him different. He came out of a house that never took poverty or coPpression for granted. My mother rocked him to the air of Connolly's rebel song: Come workers sing a rebel song, A song of love and hate, Of love unto the lowly And of hatred to the great.

The great who trod our fathers down, Who steal our children's bread, Whose greedy hands are e'er outstretched To rob the living and the dead.

My mother sang not just of hatred, but of the blessed day to come when the darkest hour would herald the brightest dawn.

Our kitchen; seven of us; my mother scrub- bing and singing. Proudly she lifts her head and belts out the end of her song.

, And labour shall rise from her knees, boys,

And claim the broad earth as her own.

My brother was a rebel with a Thousand causes. When the Italians invaded Abyssinia, our Brendan sang, 'Will you come to Abyssinia Will you come, bring your own =munition and a gun.' When, in my ignorance, I sneered at homosexuals, he turned on me like ti tiger and told me to keep my dirty ignorant thoughts to myself. Although he was only fourteen when the Spanish Civil War broke out, he moved heaven and earth to get out there.

From the very start our Brendan was the favourite son. Good-looking, with a head of dark brown eurls, he easily captivated my Granny, who worshipped the ground he walked °n. He was to lack for nothing in a street Where money was counted in halfpennies and Pennies. Bengy, we called him, and from the start felt a little in awe of this disturbing creature who could cut you up with his tongue Or his fists, as he chose. Yet running through nature's abundant cup was a thin line of Poison. For years he suffered with his nerves which caused him to stutter: He overcame this eventually, but even years later when he became exeited back it came. Underneath his ebullience he was a quivering mass of too much feeling.

Feelings deep, raw and violent that were liable to explode at the slightest provocation. Then like a mad stallion he couldn't bear to be bridled by anyone.

He first wrote for the Republican paper An Phoblact. How proud I was of his work in print. Yet I remember, I fought him that night because he taunted me about my silences.

Brendan was as Dublin' as the hills and loved every stone of it. On my father's side the Behans stretch back ten generations of Dublin bowsies. My granny Behan was a tenement landlady, fat, black and powerful as atly man. Thanks to the survival of the fittest, the breed was short, stocky and hardy. Brendan could have lived to be ninety if he had chosen to. From my father came 'his love of people, from my mother his idealism. Good, un- complicated Da. who always has a ready excuse for anyone's transgressions and in whose stubby little hands are the work of a lifetime. Fierce, wolf-like mother, who could rouse a brigade of the dead to fight for freedom. 'Out of these two came Brendan. Brendan, who challenged everything to the death and then burst out laughing as he was finished doing it. Brendan, who in his youth could keep you entertained for hours acting and mimicking and making up outrageous stories about anyone he despised. One time there was a mother in the road who was driving everyone mad boasting about how she'd sent her darling boy to Lourdes to walk in the holy procession. According to Brendan she'd sent him equipped with a pair of wooden hands, which he wore piously clasped in front, while he picked pockets with his real ones.

One of our uncles was the owner of an old Dublin music hall, The Queen's. He would often send us free passes and it was great for us boys sitting in the stalls amongst all the posh customers watching plays like The Colleen Bawn and Arrah na Pog. It's small wonder that Brendan took so well to plays and play- writing.

But like everyone else he had to work for his living, and my mother's call changed from

'Brendan, you'll be late for school' to 'Brendan, get up for your work, your father's just going out.' He followed Da as an apprentice to the painting trade. Not just a brush hand, but sign- writing and decorating. He joined the union, but only attended one or two meetings. A labour republican, he saw more in direct action than long-winded resolutions. And all the while we were splitting asunder as a family. My brother Seamus was off to fight Hitler while Rory joined the free staters and supported de Valera's neutrality. I was a Marxist and looked down my nose at republican adventurers.

One night Brendan came home to tell us that he had denounced the capitalists in his union branch for `driving along the Stillorgan Road in their brothel wagons killing the children of the poor.' Unimpressed I poured cold water on his efforts and he went away hurt and disrvayed. Yet the family feeling has never completely dried up. It still warms my heart to remember the long letters Brendan wrOte me from Borstal when I was in Artane, telling me to keep my heart up and remember it couldn't last for ever.

In the intervals when we were all at home together I never saw him but he was writing. Sitting up in bed, typewriter on his knees, he never thought of food or drink till he was finished what he was doing. Then he would come down to a great bowl of soup. Worn and unshaven, he looked a proper Bill Sikes.

In the main we were afraid of him. It wasn't just that he could be cruel and biting, he had an unpleasant habit of putting his finger right on the truth. So that when you, had a conversation with him it was like walking in a minefield, a - single lie could unleash a desperate bang.

At length he burned his paint brushes and determined to live as best he could amongst the left-bank Parisians and the arty set in Dublin. He had never had much reverence for toil. One tinie he was made foreman over, some painters doing out a hospital. My mother sent me to pick up his money for fear it might vanish in some pub. When I got to the job I proudly asked where my brother, the foreman, might be. `Ah,' said the painter, taking a swig at a bottle of Guinness, 'You mean Brendan man, he's one of' the best. Jasus, if we only had him on every job. He's out there now singing with the cleaners.' And there he was sitting on some laundry baskets between two charwomen, drunk as a monkey's uncle. He was great for organising a job of work. As the painter said, 'It's seven hours for drink and one 'for work and if that interferes with the drink vire!! get rid of it.'

I woke one morning to see the special police tearing our house apart., Brendan had shot a policeman and they told my father, 'Let him give himself up. Stephen, or he's a dead man.' My father, who had fought in the IRA with some of the specials, pleaded with them not to plug our Brendan. Two days later Brendan was sentenced to fourteen years.

By now our house had become notorious as the local Kremlin. When Brendan came out of gaol after doing about three years he found that my mother's life was being made miserable by the neighbours who were having •a persecu- tion-by-gossip campaign, calling her a Com- munist cow and other such pleasantries. He soon put a stop to that by going round the streets knocking on doors and informing all and sundry that he intended having an early Guy Fawkes night and burning down the house of anyone heard maligning his mother. Then off we went. again into the night with my, mother begging him, 'Brendan love, take cue

of yourself.' My mother was convinced by now that he was mad. Not mad in the loony sense, but mad with spirit and too much feeling that knew no bounds. Mad in the sense of too deep perceptions, of second sight almost. Mad in the sense that one minute he could be prickly and truculent and impossible to communicate with, and the next cuddly and lovable as a teddy bear.

He had a real feeling for old people. Once on a visit home I went to see my aunt Maggy Trimble. `Ah, Brian,' she said, 'your Brendan, God love him, was here yesterday in a great big car, and he nearly tore the house down knocking. "Brendan," I says, "what's wrong?" "Nothing," he shouted, "Get your coat, you and me mother are coming out for the day." "Oh Brendan," I said, "I'm too shabby, look at the cut of me, I can't ride in that big car." He only 'roared like the town bull. "To hell with poverty, we'll kill a chicken." And out he dragged me, Brian. And away the three of us went up the mountains drinking and eating to our hearts' content. Ah, God love him for thinking of an old woman.'

My mother has always had to be ready for anything. Another time he whipped her out of our kitchen, pinny and all, and the next thing she knew she was on the plane to England and a weekend at the Savoy. One night we were knocked up in the early hours to find three beautiful women bearing an unconscious Brendan into the kitchen. They laid him on the floor with all reverence while my mother ran crying round her poor cock sparrow, roundly abusing the three young women.

His friends ranged from a Dublin composer who haunted our kitchen just to hear my mother talk, to gunmen just out of gaol who drank morosely and long while they talked of various nicks and mushes. When it came to ideas Brendan was always a stirring stick. He never accepted Communism, it was too cut and dried for his liking, and the idea of party disci- pline was anathema to him. But like many writers who came out of toil and travail he supported the Russian revolution, believing it would eventually bring world freedom. Like us all he longed for the day when we would establish a new world free from hunger and poverty. In his case it was more a longing for the big rock candy mountains, a kind of tired man's heaven. He longed to go to Russia, but never made it. During the cold war the CP couldn't get enough tame clods to visit Russia and 'report back.' Brendan came to me and asked if I would use my influence to see that he got on to one of these cultural dele- gations. But the CP would never have risked send- ing him. They couldn't be sure what he would say when he came back, and a Brendan let loose in Red Square would have hastened Stalin's heart attack by a few years. Brendan ranted and raved about the idiots they were sending, while real men were left behind. He was right, all we wanted were a few castrated scribblers who would see only what we wanted them to see. Brendan had no politics, he made them up as he went along. He used to say the first Communists were some monks in Prague who agreed to hold everything in common long before Marx appeared on the scene.

As be became famous he was sought after by the rich and powerful, but he was a very chancy bedfellow. Once at Dublin airport he told re- porters that he had to go to America to earn money to support some ignoramus in the govern- ment who couldn't tell a pig from a rabbit.

When I visited Dublin from England f never sought him out. I'd seen him over here sur-

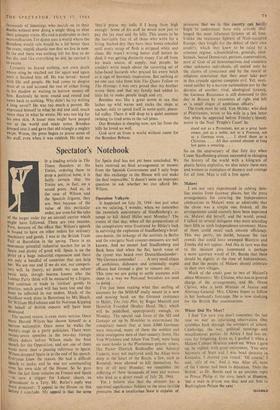

Brendan Behan's mother mid father

rounded by what appeared to me to be syco- phants and toadies, and I didn't want to seem to be one 'of them. Also I always had a sneaking fear that he'd think I wanted to sponge on him. Anyway it would bave cost a fortune to hold your own with him when it came to buying drinks. I wonder now if he didn't lose a Jot of genuine friends through this. Anyway he came twice to see me. Once bounding up the stairs in Dublin shouting, 'Why must you live like a f— monk? Why can't you come out and have a drink, like anyone else?' I started to get mad, but behind his bluster he looked so unsure and anxious that I couldn't keep it up. Another time he descended on us like a tornado in a Dublin street, and dragging me into the steamship office insisted on booking first-class fares for us all back to London.

During the strike at Shell Mex House, he paraded round to see all the pickets, congratulat- ing them on the fight and handing out money to all and sundry. Then he marched in the gate and soundly abused the scabs working inside. After, we went for a drink at the Hero of Waterloo and he told me, 'I'm proud of what you are doing,' and he meant it. A blow struck, anywhere, against any oppression or injustice, had his full support. Still, he felt a bit out of it with the rest of the strike committee. Large, strong and very manly, they were completely different from the people he had become used to drinking with. These were men you didn't fool around with. For a while he tried pressing them to drink with him, but they politely refused. He stood silent and worried he was losing contact with the very people he admired. Suddenly he smiled. A street musician came into the pub with his flute. Brendan stuffed the old man's hat with coins and notes. Then taking up the flute he dipped it in a pint of cider and slowly began playing and dancing. Out into the street he went and began begging from the passing crowds. To the old man's delight he filled the hat several times over. This was Brendan; trying to reach out through a clown's mask into the hearts of humanity.

All the while his world was crumbling. The republican movement had failed. Ten years of hunger strikes and gaols and firing squads had smashed the movement that had set out to make old Ireland free. When all the world was young we thought unstinted sacrifice and fiery faith were sure to win out. But though stone walls Could not a spirit break the released republican prisoners from Dartmoor and Wakefield came

The drawings on these pages, with that on the cover, were made by Liam C. Martin in Dublin a few weeks before Brendan Behan died in March at the age of forty-one.

This article forms part of With Breast Expanded, by Brian Behan, to be published by MacGibbon and Kee in September.

back to stare at empty grates or hurry to ihe pub to relive old battles. Time had passed them bY. The clear lines of the struggle for freedom in Russia, in Spain and in Ireland were breaking up. Russian guns at Budapest were blowing the workers' paradise to hell and a grey dust \cis falling on all the things we had held dear.

Brendan loved humanity; he believed heart and soul in its causes. He believed in the goodness of people. But the causes crumbled and his very success drove away his true friends and left him prey to the flatterers and spongers. Fame and suc- cess became his twin headstones. The more he got, the less he had. The more he drank, the less he understood what had happened to his world. He became harder and harder to put up with One night when we were celebrating the opening of The Hostage he suddenly turned on me and called me a traitorous bastard for leaving the Communist Party: the party he would never join himself. Even so, I know he tried hard. to get a grip on things. The last time we met, that is not surrounded by hordes of other people, he invited me out for a drink, but drank nothing himself. He had a beautiful tenor voice and knew all the operas, and he just sat singing to his mother and Celia, or listening to our talk. At closing time he stood outside looking so sad and pathetic that it made me cry to look at him. He took my hand and asked me what was wrong. I couldn't speak. In any case the truth was there in his own eyes. He was done for and there was nothing he or or anyone could do about it.

Bengy, our most favoured brother, smiled on by nature and people, was dying. He had all the wild wilfulness of my mother, but with no chain to bind him. Spoilt from birth by an over- abundance of talk and flattery, he denied himself nothing. People destroy people. To make a god of someone is to destroy them as surely as driving a knife into their back. Our Brendan would brook no arguments as to what he did or where and when he did it.

Self-indulgence without caring what it does to those around you can be either selfishness or generosity, depending on where you are in the firing line. I remember once at The Quare Fellow a man came up to Brendan with his hand out saying, 'I knew you years ago.' Our Brendan loudly told him to 1— off out of it.' At the time I felt ill; but then, maybe he was right, at least he lived his life without compromise in the way that • he wanted to go. Perhaps the world is smaller for mingier people like ourselves. Brendan was above all an individualist in the extreme. A man pos- sessed by demons that demanded absolute un- questioning obedience to his desires and whims. But then disillusion and boredom set in. Struggle will never kill you, boredom will. If there's noth- ing left to strive for, then you collapse like a watery jelly. Standing opposite Brendan are the

thousands of lemmings who march on to their deaths without ever doing a single thing to alter their unhappy states. His end is preferable to their mummification. I'm damn sure a World where the Brendans would rule would be a lot better than the crazy, stupid, chaotic one that we live in now. In the end there was nothing left for him to do but die, and like everything he did, he carried it to excess.

Certainly he feared nothing, not even death Whose sting he reached out for again and again Until it finished him off. He was bored : bored With life and people. He had come to despise most of us and accused the rest of either living in his shadow or waiting to borrow money off him. Restlessly he went round and round and came back to nothing. Why didn't he try writing a long novel? He was too much a person. He expressed himself in what he did and said, much More than in what he wrote. He was too big for his own skin. A lesser man might have peeped out at the world and made notes. Brendan Jumped into it and gave that old triangle a mighty swipe. Worse, the press began to praise some of Ills stuff, even when it was rubbish. He told me

'they'd praise my balls if I hung them high enough.' Some of his stuff he wrote now just to pay the tax man and the bills. This seems to be the inevitable fate of all those who write for a living. Sucked dry, they have their bones reboiled until every scrap of flesh is stripped white and clean. He wasn't writing better stuff before he died, it was getting distinctly ropey. Cut off from his main source of supply, real people, he couldn't write much about the cavorting set of false-faced bastards who praised his every belch as a sign of heavenly inspiration. But nothing or no one can take from him The Quare Fellow or The Hostage. I was very proud that my brother wrote them and that my family had added its little bit to make people laugh and cry.

Brendan was like a great storm at sea that lashes up wild waves and rocks the ships at anchor, only to spend itself in some quiet, peace- ful valley. There it will drop to a quiet murmur twining its tired arms in the tall pines.

Our Brendan is sleeping now, not far from the hills he loved so well.

God save us from a world without room for the Brendan Behans.

Previous page

Previous page