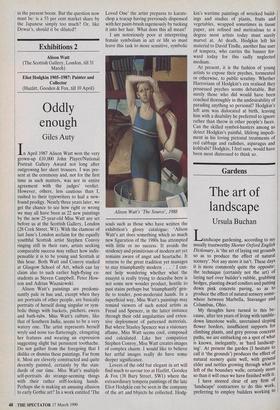

Gardens

The art of landscape

Ursula Buchan

Landscape gardening, according to my usually trustworthy Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, is 'the art of laying out grounds so as to produce the effect of natural scenery'. Not any more it isn't. These days it is more commonly quite the opposite: the technique (certainly not the art) of laying turf over builder's rubble, grubbing hedges, planting dwarf conifers and putting down pink concrete paving, so as to produce the effect of natural scenery some- where between Marbella, Stavanger and Columbus, Ohio.

My thoughts have turned to this be- cause, after ten years of living with tumble- down limestone walls, unretained sloping flower borders, insufficient supports for climbing plants, and grey porous concrete paths, we are embarking on a spot of what is known, inelegantly, as 'hard landscap- ing'. At present the garden (I hesitate to call it 'the grounds') produces the effect of natural scenery quite well, with ground elder and nettles growing through what is left of the boundary walls; certainly more so than it will once we have finished with it. I have steered clear of any firm of `landscape' contractors to do this work, preferring to employ builders working to plans instead. At least that way we should avoid ending up with a 'patio' and 'Bar-B- O' area, particularly one paved with col- oured monoblocks and surrounded by peek-a-boo concrete walling.

Why it has taken us so long to get round to this is, not surprisingly, because work of this bitty kind is inordinately expensive. However, our hesitation has been as much Psychological as financial. As I know from working on other people's gardens, there can be a disconcerting gap between ex- pectation and realisation. There seem also too many possibilities — as any architect knows, designing other people's houses is a great deal easier than planning your own.

We have not, of course, been idle in the last ten years. Timid we may be about `hard' landscape, but we are positively adventurous with the 'soft'. The borders may be wrongly sited but they burst with plants, the trees bear fruit, and the legion bulbs flourish. My husband, the Bodger, who is to DIY what Little and Large are to Comedy, has even laid a few ragged feet of a low drystone wall intended to retain a sloping border. But that was seven years ago. Since then, although mustard keen to finish it, he has not had one spare day to call his own — poor lamb. The 'wall' has now almost disappeared behind a green curtain of crevice plants crammed into what gaps there are.

In all honesty I must admit, however, that there is one corner of the garden which, because we have always been on the point of extending the house, has suffered a decade of planning blight. Consisting of an old path, on top of which someone once dumped a few inches of soil, and a broken- down low wall, this no-man's-land is duti- fully weeded but otherwise mainly left alone. Occasionally I bed it out with some of the less successful of the seed cata- logues' novelties' which I feel in honour bound to grow each year. Despite never having the mental energy to cultivate it properly when, at any moment, the buil- ders might move in, I have nevertheless found it a source of constant, if vague, shame all these years. Now someone else will be rolling up their sleeves and sorting it out. I have discovered from talking to others that many keen gardeners have little pieces of their garden which defeat them. That is both comforting and dispiriting. I am hoping that all the irritations and aesthetic shortcomings of this garden will shortly disappear. The Bodger, in a fit of generosity (the result of working when he should have been building garden walls), has finally set the whole business in train. I should be overjoyed but there is one lingering anxiety: once done, any remain- ing imperfections will no longer constitute a respectable excuse to visitors. My pride could take a battering. 'I should love to open my garden for the Church but it is not quite ready yet' will sound very hollow once the rumble of bulldozers has died away.

Previous page

Previous page