NEW FACES FOR OLD IN EASTERN EUROPE

The old communist rulers even looked

different from their replacements. Timothy Garton Ash

on the new leaders typified by Vaclav Havel

ORWELL once wrote that at 50 everyone has the face he deserves. I thought of this remark the other day when comparing the features of two men in their early fifties: the wooden, large-toothed face of Egon Krenz, briefly leader of East Germany's once ruling communist party, and the vivid, laughter-lined face of Vaclav Havel, the playwright-President of Czechoslova- kia, who pays an official visit to Britain next week.

Professional politicians of Left and Right in contemporary Western democracies do not generally look very different from each other, because their life experience is usually not so different. To be 'in or out of office' means to be sitting in one office rather than another, not in jail rather than in a palace. In Prague, Warsaw or Budapest, the difference between the old and the new ruling elites is instantly visible — even when the new leaders have re- placed their opposition jeans and sweaters with unfamiliar suits and ties.

Most politicians — most public figures — are less impressive close up than seen from afar. But even measured against low expectations the last generation of com- munist leaders in Eastern Europe was particularly unimpressive. The first genera- tion of post-war communist leaders, though often ignorant and ruthless, could at least boast some real experience of adversity, of struggle, and often of long imprisonment. Most could legitimately claim to have had, at least in their early days, the courage of their convictions. By contrast, the second generation — and there were only two! — was very largely comprised of careerists and opportunists, fat-faced men delivering endless speeches about heroism and justice and equality while thinking only of lunch.

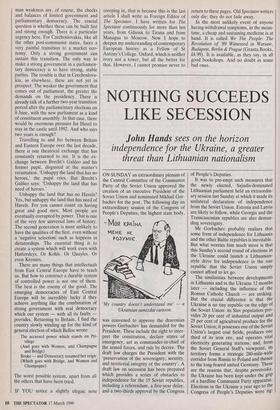

In terms of physiognomy, Roy Hatters- ley is the comparison that comes to mind. (This is not for a moment to suggest that Mr Hattersley is anything but a statesman of profound conviction, integrity and cour- age — witness his dauntless stand in defence of Salman Rushdie). The Hunga- rian Karoly Grosz had slightly more brain than the others, and slightly less Appar- atchik's Jowl, but he certainly did not deserve half the praise initially lavished upon him by, amongst others, the British Government. The Czechoslovak Commun- ist Party's Milos Jakes was a bad joke. In Prague these days you see crowds standing in front of televisions in shop windows and howling with laughter. They are watching a video-recording of Jakes speaking off the cuff to a closed Party meeting, explaining why he had to lock up Vaclav Havel. His Czech is abysmal.

And then there was Egon Krenz, to whom I spoke last month in East Berlin. He received me cordially in the villa to which he had moved from the guarded compound at Wandlitz, where he previous- ly lived with the country's other top lead- ers. In real life, his white teeth are every bit as distractingly large as in the photo- graphs. The villa is light and comfortable, with good modern furniture. On one wall there is a large oil painting, with an effusive dedication from the artist to Herr Krenz on his 50th birthday, in 1987. Curiously enough the picture is entitled `against fear'.

Herr Krenz now had time to spare: we spoke for nearly two hours. He told me he was worried that no one would give him a job. After 30 years, he said, he probably could not return to his original profession of . . . teacher. However, he was writing the memoirs of his brief time at the top. `It's a welcome distraction,' he confided. He was also publishing advance titbits in the Bild-Zeitung, So just a few weeks after being deposed as communist party leader, he had sold himself to a right-wing West German tabloid which stands for every- thing that he had supposedly worked and fought against for 40 years.

`Granny, what large teeth you have!' said one placard in the popular demonstra- tions that brought him down. But close up he was no wolf: rather a sheep in wolf's clothing. The illegitimate son of a Pomera- nian peasant woman, he grew up knowing poverty. What did socialism mean to him then? 'A better life,' he instantly replied, though quickly going on to explain that he meant a better life for everyone. When I asked him about his subsequent career, he produced an extraordinarily wooden re- citation of his successive offices and titles, talking like a Robert Maxwell biography. The one really human moment came when he described his mother's pride at his earliest successes. Otherwise, what was most interesting was just how uninteresting he was. Now, as in his childhood, having enough to eat plainly figured very high on his mental list of priorities — hence, no doubt, the Bild-Zeitung, and the West German book publisher. His spoken Ger- man was little better than Jakes's spoken Czech. His teeth were the only large thing about him. Little man, what now?

One can interpret the banality of Egon Krenz in diverse ways. One can say that this is a good illustration of the mechanism of negative selection (yes-men to the top) which was characteristic for communist systems, and contributed to their downfall. (But in that case, how do you account for the personality of Gorbachev?) Or one can say that this shows the strength of a totalitarian system, which can continue to function effectively even with such poor quality cogs. But of the banality itself there is no doubt.

So the first thing to note is that the new rulers of East Central Europe are quite simply of a much higher intellectual, moral and human quality than their predecessors.

This is true of the Catholic intellectual Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Prime Minister of the (no longer People's) Republic of Po- land, whom we saw on an official visit to Britain last month. It is true of Lech Walesa, whom we may see having tea with the Queen sooner rather than later, as President Walesa. It will almost certainly also be true of the next President of the (no longer People's) Republic of Hungary. (The likely candidates at present include a philosopher and another playwright.) Yet if Krenz might serve as an epitome of the old, Havel must be the prime exemplar of the new.

He is, for a start, an intellectual of real distinction. Of his plays, it is probably the earlier ones, The Garden Party and The Memorandum that will actually last longest. But what will, I think, last even longer is his essayistic work, which has ripened slowly over the years. He is, in fact, the outstanding literary-philosophical analyst of the Central European experi- ence under communism, and his work would have endured even had he never become a prominent opposition figure, let alone a President. Yet of course he did, and the second reason that he is an exemplar has to do with his whole biogra- phy, an almost perfect contrast to that of Krenz. (They are almost exactly the same age, Havel born in October 1936, Krenz in March 1937).

`Struggle' may be too heavy a word for someone with so much laughter in his life, although years of prison and police harass- ment would normally qualify for that de- scription. Initially, the struggle was forced upon him, for as a millionaire's son he was barred from higher education. In his twen- ties and early thirties, he was most in- volved in the theatre, although within the literary world his defence of the independ- ence of writers several times brought him into conflict with the authorities. But from 1968, and at the latest from the time of his open letter to President Gustav Husak in 1975, politics — or what he called anti- politics — inexorably take the upper hand, even though he himself constantly insists that what he wants to do, above all, is just write plays. Finally, there is the fairy-tale quality of his personal transition from prison, early in 1989, to Prague Castle at the end of 1989. Czechoslovakia's revolution, styled by Havel the `velvet' or `gentle' revolution, is — so far — the best example of peaceful transition from com- munism anywhere, and he is its unques- tioned symbol. Up at the castle, they are still clearing out Husak's furniture from the presidential offices. There are square brown armchairs of superhuman size, silently eloquent of endless non-conversations between tota- litarian rulers. Fortunately there are still some rooms with the fittings from the pre-war First Republic: Masaryk's furni- ture. Husak's ghastly pictures have mostly been removed from the walls, to be re- placed by large nudes and a prayer rug from the Dalai Lama. Havel, unlike Krenz, has no spare time at all. But dashing down the long back corridors to a press conference, he paused for a moment to show me a room with a huge ancient metal door. This was the starvation cham- ber, traditional in Central European cas- tles. He said: 'We shall use it for talks.'

The old presidential staff go on working down below. But on his upper floor, Havel has installed a Kolegium or counsel of advisers. A writer, a translator, a theatre director, a samizdat editor, and so on. Professional politicians have made a mess of things, he says, so let amateurs have a go. (Even his secretary is an amateur — an actress, of course.) Moreover, as he ex- plained in his speech to the US Congress, he feels that the time has come for intellec- tuals to take more direct political responsi- bility. They cannot, he says contentiously, `endlessly evade their responsibility for the world and conceal their dislike of politics behind an alleged need to be independent.'

Just as the Czechoslovak revolution was, in many respects, a Havel play, so now presidential policy-making is conceived theatrically: the first dramatic gesture of flying to Berlin — with the opened Wall as prop — and then to Munich; the symbolic `Central European' homage to Warsaw and Budapest; the grand, glittering trip to the United States, for nearly a week, with half the government, then the short work- ing visit to Moscow, taking the defence and interior ministers; and now Paris and Lon- don. In between, he speaks to Czechs, Slovaks and (as we now have to say) Moravians.

As soon as he got back from Washing- ton, he gave a report to 'the people of Prague' from the balcony on the old town square. It was an extraordinary, joking, colloquial little chat — like a favourite uncle recounting his adventures in Amer- ica — and he ended it by raising his hand and saying `ahor, that is, roughly, `cheerio!' Two days later he was back on the same balcony, delivering a quite diffe- rent sort of speech: a brilliantly turned, witty, yet deeply serious and profound reflection on the February 1948 communist coup and its legacy. Altogether, the speeches at home and abroad are superb. His first major speech as President, the New Year's Address which we reprinted in these pages (`The art of the impossible', 27 January), is one of the great documents of his historical moment, and this speeches here will surely be interesting.

Yet I must confess that I came away from Prague less happy than I had ex- pected to be. One can easily share the Czechs' delight and pride in their new President. But there is something slightly worrying in the sheep-like devotion of all the upturned faces, the almost messianic expectations, and the virtual cult of perso- nality in the media. It is a new and infinitely better personality, and far, far cleaner language, but is it healthy that everyone should just be repeating the same things? `If we have any more love and truth,' said a sharp young acquaintance of mine, 'I shall have to emigrate.' Yes, said a poet, 'newspeak has been replaced by lovespeak.' And when, on my last evening, I listened to a television report of Havel's meeting with the tennis star, Ivan Lend!, it sounded like nothing so much as an account of a meeting between some com- munist party leader and a hero of socialist sport. Which is precisely the kind of thing which that television reporter had probably been producing for the last 20 or 40 years.

Of course there is not much that the new people at the top can do about this. Indeed, part of the problem is that there are so few of them. Almost everyone of any calibre is already in some senior official post, but they do not reach down the hierarchy. As a result, far more has changed at the top than at the bottom. In this sense, the Czechoslovak revolution has been a victim of its own success. Moreover, there is an obvious danger in such heady adulation.

The strongest poison ever known Came from Caesar's laurel crown

I must say that I saw virtually no signs of a loss of contact with reality, let alone corruption by power. (The Foreign Minis- ter received me in unbuttoned denim shirt, cooking his own omelette as we talked.) But these are early days.

The only lasting guarantees against hu- man weakness are, of course, the checks and balances of limited government and parliamentary democracy. The crucial question is whether these can be built fast and strong enough. There is a particular urgency here. For Czechoslovakia, like all the other post-communist states, faces a very painful transition to a market eco- nomy. Only a strong government can sustain this transition. The only way to make a strong government in a parliamen- tary democracy is to have strong, stable parties. The trouble is that in Czechoslova- kia, as elsewhere, these are not yet in prospect. The weaker the government that comes out of parliament, the greater the demands on the presidency. There is already talk of a further two-year transition period after the parliamentary elections on 8 June, with the new parliament as a kind of constituent assembly. In that case, there would be enormous pressure for Havel to stay in the castle until 1992. And who says two years is enough?

Travelling to and fro between Britain and Eastern Europe over the last decade, there is one theatrical exchange that has constantly returned to me. It is the ex- change between Brecht's Galileo and his former pupil, disgusted at the master's recantation. 'Unhappy the land that has no heroes,' the pupil cries. But Brecht's Galileo says: 'Unhappy the land that has need of heroes.'

Unhappy the land that has no Havels? Yes, but unhappy the land that has need of Havels. For you cannot count on having great and good men. Most people are eventually corrupted by power. That is one of the very few universal laws of history. The second generation is most unlikely to have the qualities of the first, even without a 'negative selection' such as happens in dictatorships. The essential thing is to create a system which will work even with Hattersleys. Or Kohls. Or Quayles. Or even Krenzes.

There are many things that intellectuals from East Central Europe have to teach us. But how to construct a durable system of controlled power is not one of them. The best is the enemy of the good. The emerging democracies of East Central Europe will be incredibly lucky if they achieve anything like the combination of strong government with real democracy which our system — with all its faults provides. Returning to Britain, I find the country slowly winding up for the kind of general election of which Belloc wrote:

The accursed power which stands on Pri- vilege

(And goes with Women, and Champagne and Bridge) Broke — and Democracy resumed her reign: (Which goes with Bridge, and Women and Champagne) The worst possible system, apart from all the others that have been tried.

IF YOU notice a slightly elegaic note

creeping in, that is because this is the last article I shall write as Foreign Editor of The Spectator. I have written for The Spectator continuously for more than ten years, from Gdansk to Tirana and from Managua to Moscow. Now I hope to deepen my understanding of contemporary European history as a Fellow of St Antony's College, Oxford, which is neither ivory nor a tower, but all the better for that. However, I cannot promise never to return to these pages. Old Spectator writers only die; they do not fade away.

In the most unlikely event of anyone having withdrawal symptoms, in the mean- time, a cheap and sustaining medicine is at hand. It is called We The People: The Revolution of '89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin & Prague (Granta Books, £4.99). It is available, as they say, in all good bookshops. And no doubt in some bad ones.

Previous page

Previous page