If I had ,100,000, I would buy this picture of Margaret Thatcher

S()crates was never wider of the mark than when he said that the unexamined life is not worth living. He brushes aside some of the best lives ever led — if, that is, by 'best' we mean productive and by 'unexamined' we mean unexamined by the individual himself. This reflection occurred to me as I explored an exhibition (closing this Saturday, 17 May) at the Blue Gallery in London. Thatcher: An Exhibition of New Contemporary Art is a small collection of specially commissioned works of art and design inspired by Margaret Thatcher.

'Good Heavens,' she would say. 'What nonsense is this?' She wouldn't see the point. She hardly ever writes or talks of her feelings, her doubts, her joys or sadnesses. She does not find herself half as interesting as we do.

It is a characteristic of many tremendously valuable people that their whole lives have been gripped by a sense of external purpose. Such men and women are unselfconscious, having neither the time nor inclination to look inward. Let others be their biographers; they would see autobiography of the introspective kind as a mark of weakness.

I find such individuals very strange and wholly admirable. To feel impatient with the inward and anxious to get on with the job strikes me as one of the components of human greatness. I once asked someone close to the Baroness Thatcher whether the former prime minister was ever hurt by the satirical portraits in words and pictures that she had inspired.

My respondent placed both palms into the position of a horse's blinkers: 'Tunnelvision,' she replied. 'Her reading-matter was what came in her red boxes. It wasn't that she refused to read the more personal stuff, and it wouldn't have upset her; it was that she really wasn't interested.'

And it was true. As a junior in her office as leader of the opposition, I was often required to offer drafts for messages, forewords and appeals to which she was giving her name. Few of my drafts survived her blue pencil because I almost never found her voice. Only once did my work draw her praise. Her message to an organisation supporting voluntary associations, drafted by me, suggested that we enjoy human association best when we associate not for the sake of company but in order to achieve together a purpose outside ourselves. 'Quite right,' she said to me, and signed it.

I thought of the remark as I wandered around the Blue Gallery inspecting the exhibits. In a number of the works it appeared that Lady Thatcher's own remorseless looking-outwardness had acted as a block not only to self-examination but to the artists' window into her. too. A sculpture by Kenny Hunt, '3ft Thatcher', in coal dust and resin, a midget Baroness standing on a big 44-gallon oil drum, was wittily conceived but strangely dead in execution. Her face looked blank. Perhaps that was the artist's intention — I doubt he was a fan — but the result is more municipal than satirical, and no more unkind than the dreadful marble statue, complete with handbag (and not included in this exhibition), off which somebody mercifully knocked the head recently. That work had been meant as a monument to her where Kenny Hunt's was meant as a jibe. Both missed their mark and ended up dead-eyed and heavy.

As someone who is on the whole admiring of Margaret Thatcher, I was not in the least bothered that many of the artists were plainly antagonistic towards her. A bit of venom can bring a work to life, and were I Lady Thatcher I would prefer to be remembered in my guise as a Spitting Image puppet than as that lifeless lump of white marble. headless or otherwise. In this exhibition what disappointed me would have disappointed friend and foe alike: the failure, while depicting the external Thatcher, to get a handle on what lay within.

Indeed the exhibition is well worth visiting for that observation alone. Here is a pivotal figure in 20th-century Western history, now so universally acknowledged as important that our personal opinions of her take second place to our respect for an overwhelming historical fact, and who begins to inspire exhibitions, books and three-part television documentaries before she has even departed the stage; upon whose inner self and interior life it is proving remarkably difficult for either history or art to get any kind of a grip. Nothing we seem able to see about her as a private individual sheds much light on her public greatness. Snapshots are attempted from every angle, but the pictures keep coming out dull. Perhaps there is nothing more to be said.

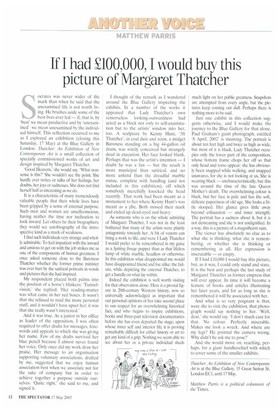

Just one exhibit in this collection suggests otherwise, and I would make the journey to the Blue Gallery for that alone. Paul Graham's giant photograph, entitled '8 April, 2002' is stunning. The portrait is about ten feet high and twice as high as wide, but most of it is black. Lady Thatcher occupies only the lower part of the composition, whose bottom frame chops her off so that only head and torso appear: she has obviously been snapped while walking, and snapped unawares, for she is not looking at us. She is wearing black — uncharacteristically, but this was around the time of the late Queen Mother's death. The overwhelming colour is black, but her face is pale and has the soft, delicate paperiness of old age. She looks a little stooped. Her glance gives little away beyond exhaustion — and inner strength. The portrait has a sadness about it, but it is not demeaning and she is not undignified. In a way, this is a picture of a magnificent ruin.

The viewer has absolutely no clue as to what she is thinking, what she is remembering, or whether she is thinking or remembering at all. Her expression is inscrutable — or empty.

If I had £10,000 I would buy this picture, but, as it was, I could only stand and stare. It is the best and perhaps the last study of Margaret Thatcher as former empress that will ever appear. In time it will become a feature of books and articles illustrating her later years, and for as long as she is remembered it will be associated with her.

And what is so very poignant is that, were she to visit the exhibition, that photograph would say nothing to her. 'Well, dear.' she would say. 'I don't much care for that. No colour. Perfectly miserable. Makes me look a wreck. And where are my legs? He pointed the camera wrong. Why didn't he ask me to pose?'

And she would move on, reaching, perhaps, for a giant handkerchief with which to cover some of the smaller exhibits.

Thatcher: An Exhibition of New Contemporary Art is at the Blue Gallery, 15 Great Sutton St, London EC1, until 17 May.

Matthew Parris is a political columnist of the Times.

Previous page

Previous page