Mighty man?

Anthony Storr

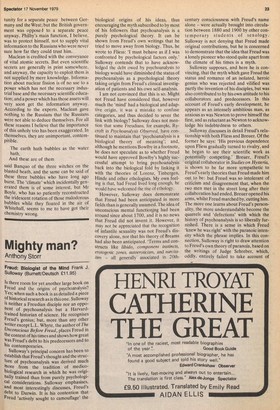

Freud: Biologist of the Mind Frank J. Subway (Bumett/Deutsch £11.95) Is there room for yet another large book on Freud and the origins of psychoanalysis? 'Yes; when such a book is as detailed a piece Of historical research as is this one. Subway is neither a Freudian disciple nor an opponent of psychoanalysis but a Harvardtrained historian of science. He recognises Freud's genius; but, more than any other Writer except L.L. Whyte, the author of The Unconscious. Before Freud, places Freud in the context of his times and shows how great was Freud's debt to his predecessors and to his contemporaries. Subway's principal concern has been to establish that Freud's thought and the structure of psychoanalysis was derived much more from the tradition of medicobiological research in which he was originally trained than from purely psychological considerations. Sulloway emphasises, and most interestingly discusses, Freud's debt to Darwin. It is his contention that Freud 'actively sought to camouflage' the biological origins of his ideas, thus encouraging the myth subscribed to by most of his followers that psychoanalysis is a purely psychological theory. It can be shown from Freud's own writings that he tried to move away from biology. Thus, he wrote to Fliess: must behave as if I was confronted by psychological factors only.' Sulloway contends that to have acknowledged the debt owed by psychoanalysis to biology would have diminished the status of psychoanalysis as a psychological theory taking origin from Freud's clinical investigation of patients and his own self-analysis.

I am not convinced that this is so. Might not Freud have considered that, however much the 'mind' had a biological and adaptive origin, it was a mistake to confuse categories, and thus decided to sever the link with biology? Sulloway does not mention that some Freudians, for example, Rycroft in Psychoanalysis Observed, have continued to maintain that 'psychoanalysis is a biological theory of meaning'; and, although he mentions Bowlby in a footnote, he does not speculate as to whether Freud would have approved Bowlby's highly successful attempt to bring psychoanalysis back into the biological fold by linking it with the theories of Lorenz, Tinbergen, Hinde and other ethologists. My own feeling is that, had Freud lived long enough, he would have welcomed the rise of ethology.

However, Sulloway does demonstrate that Freud had been anticipated in more fields than is generally assumed. The idea of unconscious mental functioning had been around since about 1700, and it is no news that Freud did not invent it. However, it may not be appreciated that the recognition of infantile sexuality was not Freud's discovery alone, nor that his theory of Mreams had also been anticipated. 'Terms and constructs like libido, component instincts, erotogenic zones, autoerotic ism, and narcissism — all generally associated in 20th century consciousness with Freud's name alone — were actually brought into circulation between 1880 and 1900 by other contemporary students of sexology. Sulloway is not denying that Freud made original contributions, but he is concerned to demonstrate that the idea that Freud was a lonely pioneer who stood quite apart from the climate of his times is a myth.

Sulloway supposes, and here he is convincing, that the myth which gave Freud the status and romance of an isolated, heroic genius who was rejected and vilified was partly the invention of his disciples, but was also contributed to by his own attitude to his collaborators and predecessors. In this account of Freud's early development, he appears as an intensely ambitious man, as anxious as was Newton to prove himself the first, and as reluctant as Newton to acknowledge his indebtedness to others.

Sulloway discusses in detail Freud's relationship with both Fliess and Breuer. Of the former he says: 'His previous dependence upon Fliess gradually turned to rivalry, and he began to see their scientific work as potentially competing.' Breuer, Freud's original collaborator in Studies on Hysteria, is shown to be far more sympathetic to Freud's early theories than Freud made him out to be: but Freud was so intolerant of criticism and disagreement that, when the two men met in the street long after their collaboration had ended, Breuer opened his arms, whilst Freud marched by, cutting him. The more one learns about Freud's personality, the more understandable become the quarrels and 'defections' with which the history of psychoanalysis is so liberally furnished. There is a sense in which Freud 'knew he was right' with the paranoic intensity which the phrase implies. In this connection, Sulloway is right to draw attention to Freud's own theory of paranoia, based on the writings of Judge Schreber, which, oddly, entirely failed to take account of Schreber's actual childhood and the tyrannical character of his pedagogue father. As Breuer wrote: 'Freud is a man given to absolute and exclusive formulations; this is a psychical need which, in my opinion, leads to excessive generalisation.'

All original thinkers tend to fall in love with their own ideas, and Freud was no exception. He also had a sense of destiny, and imagined that his house would bear a plaque recording his discovery of the meaning of dreams, and that a statue to him might be erected bearing the Sophoclean inscription to Oedipus: 'Who divined the famed riddle and was a man most mighty.' Great creators often have more than a touch of arrogance; but what Sulloway brings out is the need of disciples for archetypal heroes. Freud's self-analysis is habitually referred to as heroic, as if no-one else had ever explored their own depths. His early work is almost always recorded as having met with rejection. For example, The Interpretation of Dreams is generally reported as having been ignored. Sulloway shows that, although it is true that the book sold very few copies, 'it was widely and favourably reviewed in popular and scientific periodicals'.

The more one gets to know other human beings intimately, the more does one realise that we all have feet of clay, and that the need for heroes bespeaks a delayed adolescence on the part of the worshipper. No doubt Freud connived to some extent with the wishes of his followers in aspiring to a Promethean stature to which he was not wholly entitled. But he did in fact alter Western man's way of regarding himself and became what Auden called 'a whole climate of opinion'. Very few men achieve as much as that.

Previous page

Previous page