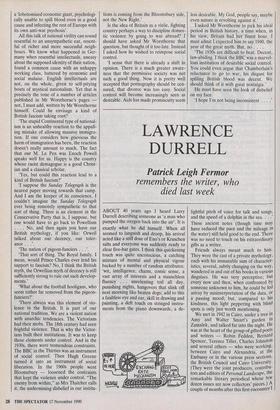

HIS FINEST HOUR

Ian Buruma talks to

Peregrine Worsthorne about Britishness

THERE is much about Peregrine Wors- thorne that reminds me of the Kelloggs Cornflakes packet, the one with the Spit- fires and Hurricanes on the back. Look at almost any Worsthorne editorial in the Sunday Telegraph, especially recent ones about the crisis in the Gulf, and you will find the ringing phrases of that Finest Hour: . . shoulder to shoulder with the Americans . . . sorts out the men from the boys . . . baptism by fire . . . . We were the kind of people who would stop at nothing to give the Axis power a good hiding,' and so on.

All stirring stuff, of course, but I some- times wonder — and I'm not the only one — if the myth of 1940 isn't holding Britain back in a world which has moved on from Spitfires and Hurricanes.

Mr Worsthorne, legs in elegant striped worsted planted firmly on the table in front of him, shakes his head wearily: 'That is what most educated commentators affirm. But the Gulf crisis shows that the "myth", as you call it, is something Europe should be thankful for, rather than consider as an eccentricity. Because we were not def- eated, we have a continuous tradition which Europe doesn't have. We ought to cherish it. For it is the lack of that myth which stops France, Germany and the rest of them from doing the necessary.'

Doing the necessary, standing up to be counted, the 'readiness to go to war to punish evil doing', are what Mr Wors- thorne most admires in what he calls the national character (another phrase redo- lent of bygone days).

`A nation defines itself to some extent by the willingness of its people to die for the nation. The German willingness to do this is as low as can be. Indeed, Germany can be said to be a busted flush. So in that respect Britain is a far more formidable nation than Germany. I think the greatest danger now is a supine Europe, where nationalism is so attenuated that nobody can envisage the trauma of sacrifice. I have always thought that if the Russians really assess their chances of getting away with an act of aggression against European coun- tries, only the British would be mad enough to push the button.'

`What about the French?'

`They might not. They'll always believe that they can outwit their opponents, that they're cleverer than anybody else. They'll make a deal. No, when things can't get sorted out, Britain is the only nation prepared to fight.'

It is difficult to imagine Mr Worsthorne as a gung-ho militarist. His long, white hair, studiedly dishevelled, his striped shirts, his beautifully cut suits, his culti- vated, and ever so slightly affected upper class speech, all leave the impression of a gentlemanly aesthete, a litterateur, more at home with fine claret and rare books than tanks and guns, a man altogether too fastidious for the deathly stink of war.

Indeed, there is something mannered about Mr Worsthorne, the consummate English gentleman, something that re- minded me of other Englishmen, all of whom were frightfully English, yet not quite English: a judge in Hong Kong, for example, who wore bowler hats at the height of the tropical summer, and cruised around Brunei with a crested flag on his borrowed Rolls Royce. The judge turned out to be a complete fraud, the son of a

Jewish tailor from Russia, who had made up his double-barrelled name, and wrote a fictitious account of his wartime heroism in his entry in Who's Who.

Mr Worsthorne is not a fraud, but his Belgian ancestry is often mentioned, a little snidely, by people who call his rather theatrical Englishness into question. I put this to him, politely. The striped worsted legs unfolded and the generous Wors- thorne mouth took on an expression of gentlemanly amusement.

`Oh, I don't think the fact that my grandfather was a Belgian has much to do with my outlook. My father was born here.

He was brought up absolutely as an En- glishman — went to Eton, joined the Irish Guards. He changed the family name, when he ran for Parliament. He didn't think Koch de Gooreynd terribly suitable

for an MP. My grandfather put in a bid to buy the Times, you know. I often think it would have been fun to own the Times.'

I thought of my own relatives, who arrived here a little over a century ago, not

long before Mr Worsthorne's grandfather.

To my grandfather England represented an island of tolerance and civilisation, or, as Arthur Koestler once put it, a Davos for exhausted Europeans. This idea of Eng- land, as a stable place of refuge from a turbulent Continent, is not unrelated to the myth of 1940, of England standing alone against the forces of barbarism. I asked Mr Worsthorne whether he still saw the world this way. `Yes, I think I do feel that Britain is an oasis of stability. Our institutions are much more deeply rooted than those on the Continent. Politically, France is still a highly disreputable country. Germany, if you like, has been an occupied country for 40 years. It hasn't been tested. Now it is going to be unified, this could be a very ugly period for Germany.' The more I heard Mr Worsthorne talk, the more I began to hear echoes of an even earlier time than 1940. The idea of Britain as uniquely virile, going her own way, while her neighbours, disreputable and too effete to fight, sink into cowardly passivity. This sounds like a German nationalist talking in the early decades of this century, except that the national roles appear to have been reversed: Britain's national character is manly and fighting fit, while Germany is described in a recent column as a `lobotomised economic giant, psychologi- cally unable to spill blood even in a good cause and infecting the rest of Europe with its own anti-war psychosis'.

All this talk of national virility can sound resentful to an unsympathetic ear, resent- ful of richer and more successful neigh- bours. We know what happened in Ger- many when resentful intellectuals, uneasy about the supposed identity of their nation, found a common cause with an unhappy working class, battered by economic and social malaise. English intellectuals are not, on the whole, given to self-pitying bouts of mystical nationalism. Yet that is precisely the tone of a number of articles published in Mr Worsthorne's pages not, I must add, written by Mr Worsthorne himself. Could he envisage a kind of British fascism taking root?

`The stupid Continental type of national- ism is an unhealthy reaction to the appall- ing mistake of allowing massive immigra- tion. If one considers how grievious the harm of immigration has been, the reaction doesn't really amount to much. The fact that our M. Le Pen was Enoch Powell speaks well for us. Happy is the country whose racist demagogue is a good Christ- ian and a classical scholar.

`Yes, but could this reaction lead to a kind of British fascism?'

`I suppose the Sunday Telegraph is the nearest paper moving towards that camp. And I am the keeper of its conscience. I couldn't imagine the Sunday Telegraph ever being remotely sympathetic to that sort of thing. There is an element in the Conservative Party that is, I suppose, but one would have to go back to Powellism . . . No, and then again you have our British mythology, if you like: Orwell talked about our decency, our toler- ance .

`The nation of pigeon-fanciers . .

`That sort of thing. The Royal family. I mean, would Prince Charles ever lend his support to fascism? No, I think the British myth, the Orwellian myth of decency is still sufficiently strong to rule out such develop- ments.'

`What about the football hooligans, who seem rather far removed from the pigeon- fanciers?'

`There always was this element of vio- lence in the British. It is part of our national tradition. We are a violent nation with anarchic tendencies. The Victorians had their mobs. The 18th century had seen frightful violence. That is why the Victor- ians built their institutions. It was to keep these elements under control. And in the 1930s, there were tremendous constraints. The BBC in the Thirties was an instrument of social control. Then Hugh Greene turned it into an instrument of social liberation. In the 1960s people went Bloomsbury — loosened the contraints that kept the violence under control. "The enemy from within," as Mrs Thatcher calls it, the undermining disbelief in our institu-

tions is coming from the Bloomsbury side, not the New Right.'

Is the idea of Britain as a virile, fighting country perhaps a way to discipline domes- tic violence by going to war abroad? I should have asked Mr Worsthorne that question, but thought of it too late. Instead I asked how he wished to reimpose social control.

`I sense that there is already a shift in opinion. There is a much greater aware- ness that the permissive society was not such a good thing. Now it is pretty well accepted that pornography should be cen- sured, that divorce was too easy. Social control will become increasingly seen as desirable. Aids has made promiscuity seem less desirable. My God, people say, maybe even nature is revolting against it.'

I asked Mr Worsthorne to pick his ideal period in British history, a time when, in his view, Britain had her finest hour. I must admit I expected him to say 1940, the year of the great myth. But, no . .

`The 1930s are difficult to beat. Decent, law-abiding. I think the BBC was a marvel- lous institution of desirable social control. You could even argue that Chamberlain's reluctance to go to war, his disgust for spilling British blood was decent. We should think of it with great nostalgia.'

He must have seen the look of disbelief on my face.

I hope I'm not being inconsistent . . .

Previous page

Previous page