The dwellings of the wilderness

James Knox

THE AMERICAN COUNTRY HOUSE 1870-1940 by Clive Aslet

Yale, f22.50, pp. 300

THE ARCHITECT AND THE AMERICAN HOUSE 1890-1940 by Mark Alan Hewitt

Yale, £35, pp. 310

It is easy to imagine Clive Aslet's sur- prise if as deputy editor of Country Life he was suddenly transported to an American country house in the 1920s. He would certainly have felt at home with its eleva- tion, which more likely than not would have been borrowed from a number of English sources. But what would he have made of the playhouse, a vast indoor complex of swimming pool, bowling alley, tennis court and riding school, which mere- ly echoed a similar range of outdoor facilities? His knowledge of architecture and ironical turn of phrase which in Eng- land would have made him such a perfect guest in the country, would, in America, be of no use whatsoever.

For the grandest American country houses were designed as leisure palaces, which left their occupants little time or inclination for any wearying sense of duty to the village, let alone to establishing their country seats as centres of political or literary influence. If you were lucky, Edith Wharton might visit, or if you were un- lucky, her partner in interior decoration, Ogden Codman, who would try and sell you expensive antique clutter to lend 'age' to every available surface.

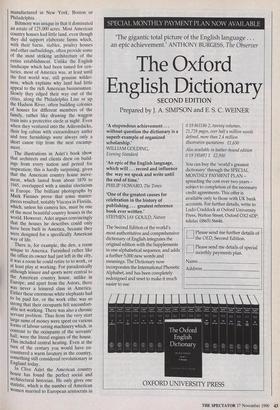

The country house building boom only took off after the Civil War, its leaders being the new millionaires of the 1870s and 1880s. They were responsible for spectacu- lar piles such as Biltmore, designed by William Morris Hunt for George Washing- ton Vanderbilt. The façade was inspired by most of the chateaux of the Loire, but there was nothing 16th-century about the ground plan which reveals all the ruthless logic of the Beaux Arts tradition with immense spaces leading into one another largely without doors; in fact it can be argued that this arrangement was the precursor of that bane of post-war domes- tic architecture, the open-plan room. The furniture was either antique, collected on buying sprees in Europe, or antique, The South Facade, Vizcaya, Florida manufactured in New York, Boston or Philadelphia.

Biltmore was unique in that it dominated an estate of 125,000 acres. Most American country houses had little land, even though they did support elaborate farms which, with their barns, stables, poultry houses and other outbuildings, often provide some of the most striking architecture of the entire establishment. Unlike the English landscape which had been tamed for cen- turies, most of America was, at least until the first world war, still genuine wilder- ness, which explains why land had little appeal to the rich American businessman. Slowly they edged their way out of the cities, along the Philadelphia Line or up the Hudson River, often building colonies of houses for different members of the family, rather like drawing the waggon train into a protective circle at night. Even when they ventured into the Adirondacks, their log cabins with extraordinary antler and tree furnishings were always only a short canoe trip from the next encamp- ment.

The illustrations in Aslet's book show that architects and clients drew on build- ings from every nation and period for inspiration; this is hardly surprising, given that the American country house move- ment, which lasted from about 1870 to 1945, overlapped with a similar electicism in Europe. The brilliant photographs by Mark Fiennes prove that some master- pieces resulted, notably Vizcaya in Florida, which, unless his camera lies, must be one of the most beautiful country houses in the world. However, Aslet argues convincingly that the houses he describes could only have been built in America, because they were designed for a specifically American way of life.

There is, for example, the den, a room unique to America. Furnished rather like the office its owner had just left in the city, it was a room he could retire to to work, or at least play at working. For paradoxically although leisure and sports were central to the American country house, unlike in Europe, and apart from the Astors, there was never a leisured class in America. Either these enormous white elephants had to be paid for, or the work ethic was so strong that their occupants felt uncomfort- able not working. There was also a chronic servant problem. Thus from the very start large sums of money were spent on various forms of labour-saving machinery which, in contrast to the occupants of the servants' hall, were the literal engines of the house. This included central heating. Even at the turn of the century you would have en- countered a warm lavatory in the country, something still considered revolutionary in England today. In Clive Aslet the American country house has found the perfect social and architectural historian. He only gives one statistic, which is the number of American Women married to European aristocrats in 1915 (he does so to explain the influence of certain architectural styles). By contrast, Mark Alan Hewitt in a rival publication bombards us with statistics and wastes much of his book's generous format, not granted to Aslet, with dull ground plans. He is, however, interesting on what has happened to these houses since the war, when despite the enormous prosperity of America in the 1950s and 1960s many of them have been either demolished and their site and gardens sold for building or they have been turned into institutions. Because these houses were such recent creations, their owners, unlike in England, probably lacked the stomach to fight for their preservation. It is obviously time to mount an exhibition at the Metropolitan entitled 'The Destruction of the American Country House' to point out to Americans that they are in the process of losing an important part of their architectural herit- age.

Previous page

Previous page