"INNES ' S WORKING OF THE NEW SYSTEM

IN THE WEST INDIES.

THE name of INNES is well known in connexion with the Western Indies ; and a namesake, probably a partner of the house, " having often experienced inconvenience from never having been in those colonies," betook himself thither in September last, to observe the workings of the Emancipation Act. Previous to departing, he waited on the Colonial Secretary, to ascertain whether there were any points on which Government desired in- formation; and was furnished by Mr. SPRING RICE with certain beads of inquiry, and with letters of introduction to the Colonial Governors. Thus armed, our traveller performed his intended tour of observation; investigating the different arrangements made for the remuneration of "over hours" between masters and apprentices, the respective management of estates by proprietor or agent, and the different costs and profits of both modes, as well as the various methods of cultivation pursued on different plantations, and their effects: he has also inquired into the general character, behaviour, and condition of the Negroes ; and addressed the re- sult of the whole, in the form of a letter, to Lord GLENELG.

It will be understood, of course, that Mr. INNES'S report is not a book of travels; and that it advances no claims to distinction in a literary point of view. It is, however, what it professes to be— the work of a plain man of business, who is able to collect facts with industry and arrange them with clearness, but who is better qualified to pronounce an opinion as to the immediate practical working of single cases, than to deduce conclusions frou the whole of the circumstances which passed under his notice. Hence, many readers will be apt to derive more of hope from his facts than he himself, and to think that the plan of ap- prenticeship may turn out better than our author deems likely. Three important points, at all events, are clearly established,— first, that the Emancipation Act does not neceskrily contain the elements of failure; second, that Negroes will work well in a state of freedom, especially if very simple means be taken to prepare them for it ; third, that the distres:.es of the Wcst Indians mostly arise from their own misconduct, aggravated by certain local causes quite independent of slaves and slavery. Upon the first point, it is merely necessary to observe, that out of eleven* colonies visited by Mr. Isms, one (Antigua) had freed the slaves; in four inure the Apprenticeship Act was working well, in three doubtfully, and in four badly,—this term being limited to dogged and sullen labour, an evil which was heightened if not caused by want of management on the part of the masters. It should also be observed, that the apprehensions of the planter on the expiration of the Act were entirely confined to a deficiency of workmen on sugar plantations. For the cul- tivation of coffee, ginger, cotton, and other productions, they :onceived there would be no difficulty in finding labourers, ior even for work to be done about the sugar-houses. But it seems that field labour is held degrading, by having been made a punishment for ill-behaviour; and hence the aversion of the Negroes to cane cultivation,—a prejudice difficult to contend against, but certainly not insurmountable.

The probability of continuous labour from a free Negro depends upon a variety of circumstances. Where the productive land, as at Barbadoes and Antigua, is for the most part appropriated, Negroes have no choice between work and hunger ; but Mr. Isms is inclined to think that education, by creating artificial wants and giving rise to a sense of social duty, is equally efficaci- ous with the more vulgar necessity. It should, however, be borne in mind, that labour, in Colonial language, has a peculiar signifi- cation. A man may raise provisions and carry them to market, he may catch and cure fish, or he may work as a mechanic; but in the mouth of a planter, nothing save raising sugar is to be called labour. That, at first starting, a rush into the more esteemed employments may take place, is probable ; but this is an evil that will soon cure itself, although some inconvenience may be suffered in the transition,—unless it should be found ad- visable to discontinue the cultivation of sugar for more profitable commodities.

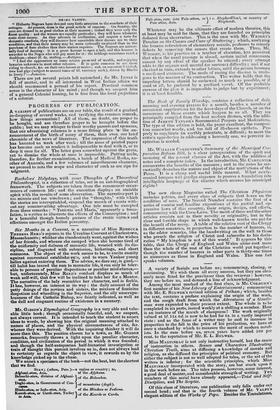

* Their names are contained in the following table, classified according to the manner in which the Act was working.

WELL. DOUBTFULLY. BADLY.

Antigua (declared free) Dominica Nevis Barbadoes St. Vincent's British Guiana Grenada Trinidad Jamaica St. Kitt's St. Lucia

It should, however, be remarked upon the Doubtful list, that Dominica had been ravaged by a hurricane, which had alike destroyed the property and the spirits of the planter. As regards the third column—at Nevis, the Act was working worse than anywhere, partly because there was neither police nor means of inflicting punishment, partly from the inexperience of the managers; in British Guiana, the apprentices were employed, but mostly doggedly ; in Jamaica—a singular circumstance—the Negroes were found better off in cir- cumstances than in any other colony, but more disrespectful to the Whites, whilst there was more ill-blood between the two classes than elsewhere,— arising, Mr. INNEs conceives, from the absence of resident proprietors, and the immoral state of the White population. As regards the distress of the West Indians, Mr. INNES'S state ments prove, what has often been asserted in our columns, that absenteeism is one great cause of the planters' embarrassments. The agent, however conscientious, has not the power to act promptly according to circumstances ; nor is he willing to run the risk of deviating from routine practice. Hence, at the best, an inert anti mechanical mode of management takes place. In many cases, however, the agents are incompetent; and, in Jamaica especially, their cupidity induces them to take the management of more properties than they can properly attend to; whilst not un- frequently the agent has private interests directly opposed to those of the proprietor. A resident planter's family also produces a considerable moral effect upon the Coloured population; whereas the example of the bachelor Whites employed on the estates is any thing but Md.) ing. These matters are beyond legislative power ; some mischievous causes exist which laws can remedy. The currency, throughout all the Colonies, is variable, and the cause of much inconvenience and loss. Mr. INNES suggests that the English standard should be established throughout. In foreign colonies, the state of the law and the persons chosen to the judicial office create much evil. Thus, in the fine island of Trinidad, no prudent capitalists can attempt to settle, because the Colonial Acts and the Orders in Council, which have been added to the old Spanish law, have pro- duceJ such a hodgepodge, that no care can render a title secure. In several other islands, there are legal abuses arising from the mixture of English and foreign jurisprudence; and though one lawyer is appointed as judge, he is joined with two colonial civilians, who very possibly are interested in the causes brought before them.

We have spoken generally. A few details from the pamphlet may produce a more exact impression. The name of the colony to which each extract refers is added, that the reader may have the whole case before him.

EFFECTS OF IMPROVED MANAGEMENT.

a From all I have heard during my tour, I am convinced that the produce of sugar estates might be increased, and the expenses diminished, by the introduc- timi of the modern improvements in Eneish agriculture. In support of this opinion, I may quote the experience of a gentleman in the island, who in a few Vears has rendered most important services to the colony. Although not brought up to farming, he had attended to the cultivation of a piece of land near his residence in Yorkshire. Being a man of research, he sought informa- tion from agricultural publications and practical farmers, and soon acquired considerable knowledge. Finding his estate in this island managed at great ex- pense in proyortion to its crops, he determined to visit it, and endeavour to discover the cause and apply a remedy. After residing a short time on his plantation, he took the management into his own hands. Ruin was univer- sally predicted. Instead of the verification of this prediction, he is now ad- niitied to be one of the most enlightened as well as successful planters in the island. Ile has greatly reduced expenses (in some departments more than one- half), and he has almost doubled the crops."—St. Vincent.

A BSENTEISM RESIDENCE. A BSENTEISM RESIDENCE.

" There is a fine estate here which I believe will not pay its expenses this year from the crop, and it is the general opinion that next year's crop would to tla proprietor In unproductive; yet the gentleman who has charge of it has just taken it on lease, at a rent of 1000/. sterling per annum for the first three years, and 1200/. a year thereafter; considering, no doubt, that when freed from the restricted authority of an agent, and invested with the power of a principal, he will be able to bring back and retain the labourers who have left the estate. It is supposed that he will realize largely by the lease ; and the pro- prietor has at the same time a certain income, good security being given for the rent. Other estates have been let recently, on terms supposed to be bene- ficial alike to landlord and tenant."—Antiqua. "I am acquainted with an instance of an overseer having recently offered a liberal rent, with good security, for an estate which has been unproductive to the proprietor for several years past; and I have heard of many negotiations now in progress."—Jamaica. "The two leading evils of this island are, absenteeism and what may be termed a monopoly of attorneyships ' • these place the Negroes at a distance from those to whom they ought to be able to look as their best friends. There are whole parishes with scarcely a resident proprietor of magnitude; and in an ex- amination into the working of the apprenticeship which took place before a Committee of the House of Assembly in November last, it will be seen, by the Parliamentary papers, that one gentleman was examined who had forty- eight estates' with a population of about 10,000, under his charge. Another witness had charge of twenty. nine estates (besides one of his own), with from 7000 to 8000 apprentices. When the size and population of estates are considered, it will be obvious that only a nominal superintendence can be exer- cised by such attornies' even when the isroperties are contiguous; but that when they are scattered, as is frequently the case, no one not gifted with ubi- quity can even go through the form of attending to many of the important du- ties of an attorney. There are instances of estates upwards of a hundred miles distant from each other being under the same attorney : and a hundred miles here, considering the climate, roads, and modes of conveyance, are equal to two hundred miles in England."—Jamaica.

PROSPECTS FOR COFFEE-PLANTERS.

" As far as I can learn, it is the prevailing opinion of planters, that free Negroes will work on cotton and coffee-plantations; and therefore I deem it superfluous to direct attention to thern."—British Guiana. " The abstraction of labour will, in all probability, be almost exclusively from the sugar estates. The coffee-planters are so little apprehensive of being injured by the termination of the apprenticeship, that I have witnessed instances of increasing cultivation, andahave heard of the contemplated establishment of new plantations as well as of speculations for raising ginger, pimento, and to- bacco, by free labour. When all are free, it is not be expected that the growers of such atticles will have difficulty in procuring labourers."—Jamaica.

NEGRO PREPARATIONS.

"It is clear the Negroes do not generally contemplate the abandonment of their present dwellings ; for it has been observed in almost every quarter, that when a Negro has to repair or build a cottage, he is doing so more substantially and with greater care than formerly, under the persuasion that at the end of the apprenticeship it will become his own. I have heard of many instances of ap- prentices who, wishing to buy their freedom, and in some cases having even gone the length of paying for it, withdrew from tbe etract on learning that freedom would be accompanied by the forfeiture a their dwellings and pro- vision-grounds."—Jamaica.

11113Z0 VANITY.

" Hitherto Negroes have devoted very little attention to the comforts of their cottages. At present, dress is the great article of expense. On Sunday, the men are drooled in as good clothes as their masters ; indeed they wear only the finest quality : and the women are equally particular; they will have whatever costs most money. As they advance in civilization, and acquire a taste for domestic comforts, they will discover how unsuitable their dresses are to their condition, and that their money may be more rationally employed than in the purchase of finer clothes than their station requires. The Negroes are univer- sally fond of dancing : it is a great honour to open a ball, and this honour is awarded to the Negro who will pay most for it : the biddiogs sometimes leach a doubloon—about 3/. 4s. sterling.—.Antiyuo. " I find the apprentices on some estates poresed of wealth, and enjoying luxuries unknown in most other colonies. It is quite common to see them riding to church, Sze. on their own horses or mules ; and, on one estate I visited, two had gigs (subject to annual taxes of 6/. currency each), driven by Blacks in livery l"—Jamaicci.

There are yet several points left untouched ; for Mr. INNES is full of matter, and to all interested in West Indian affairs we should recommend a perusal of his report. Practical common sense is the character of his mind ; and though we suspect him of a general Colonial leaning, he is free from the local prejudices of a colonist.

Previous page

Previous page