Exhibitions 2

A surfeit of rapture

Roger Kimball

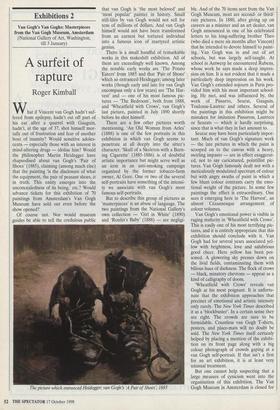

What if Vincent van Gogh hadn't suf- fered from epilepsy, hadn't cut off part of his ear after a quarrel with Gauguin, hadn't, at the age of 37, shot himself mor- tally, out of frustration and fear of another bout of insanity? Would sensitive adoles- cents — especially those with an interest in mind-altering drugs — idolise him? Would the Ohilosopher Martin Heidegger have rhapsodised about van Gogh's 'Pair of Shoes' (1885), claiming (among much else) that the painting 'is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. This entity emerges into the unconcealedness of its being,' etc.? Would advance tickets for this exhibition of 70 paintings from Amsterdam's Van Gogh Museum have sold out even before the show opened?

Of course not. Nor would museum guides be able to tell the credulous public that van Gogh is 'the most beloved' and `most popular' painter in history. Small still-lifes by van Gogh would not sell for tens of millions of dollars. And van Gogh himself would not have been transformed from an earnest but tortured individual into a famous icon of martyred artistic genius.

There is a small handful of remarkable works in this makeshift exhibition. All of them are exceedingly well known. Among the notable early works are 'The Potato Eaters' from 1885 and that 'Pair of Shoes' which so entranced Heidegger; among later works (though early and late for van Gogh encompass only a few years) are 'The Har- vest' and — one of his most famous pic- tures — 'The Bedroom', both from 1888, and Wheatfield with Crows', van Gogh's last picture, painted in July 1890 shortly before he shot himself.

There are a few other pictures worth mentioning. 'An Old Woman from Arles' (1888) is one of the few portraits in this exhibition in which van Gogh seems to penetrate at all deeply into the sitter's character. 'Skull of a Skeleton with a Burn- ing Cigarette' (1885-1886) is of doubtful artistic importance but might serve well as an icon in an anti-smoking campaign organised by the former tobacco-farm owner, Al Gore. One or two of the several self-portraits have something of the intensi- ty we associate with van Gogh's most famous self-portraits.

But to describe this group of pictures as `masterpieces' is an abuse of language. The two paintings from the National Gallery's own collection — 'Girl in White' (1890) and `Roulin's Baby' (1888) — are negligi- The picture which entranced Heidegger: van Gogh's 'A Pair of Shoes, 1885 ble. And of the 70 items sent from the Van Gogh Museum, most are second- or third- rate pictures. In 1880, after giving up on careers as a minister and an art dealer, van Gogh announced in one of his celebrated letters to his long-suffering brother Theo (who died a mere six months after Vincent) that he intended to devote himself to paint- ing. Van Gogh was in and out of art schools, but was largely self-taught. At school in Antwerp he encountered Rubens, whose work he says made a deep impres- sion on him. It is not evident that it made a particularly deep impression on his work. Van Gogh's extended sojourn in Paris pro- vided him with his most important school- ing. He met, and was influenced by, the work of Pissarro, Seurat, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec and others. Several of the paintings in this exhibition might be mistaken for imitation Pissarros, Lautrecs or Seurats — which is hardly surprising, since that is what they in fact amount to.

Seurat may have been particularly impor- tant. Much of van Gogh's signature work — the late pictures in which the paint is scooped on to the canvas with a heavy, swirling impasto — are in effect exaggerat- ed, not to say caricatured, pointillist pic- tures. Van Gogh famously dealt not with a meticulously modulated spectrum of colour but with angry swaths of paint in which a few blunt colour contrasts carry the emo- tional weight of the picture. In some few paintings the effect is extraordinary. One sees it emerging here in 'The Harvest', an almost azannesque arrangement of colour volumes.

Van Gogh's emotional power is visible in raging maturity in Wheatfield with Crows'. This is easily one of his most terrifying pic- tures, and it is entirely appropriate that this exhibition should conclude with it. Van Gogh had for several years associated yel- low with brightness, love and salubrious good cheer. Here yellow has been poi- soned. A glowering sky presses down on the livid fields, contaminating them with bilious hues of darkness. The flock of crows — black, minatory chevrons — appear as a kind of calligraphy of doom.

Wheatfield with Crows' reveals van Gogh at his most poignant. It is unfortu- nate that the exhibition approaches that precinct of emotional and artistic intensity only rarely. The New York Times described it as a 'blockbuster'. In a certain sense they are right. The crowds are sure to be formidable. Countless van Gogh T-shirts, posters, and place-mats will no doubt be sold. The New York Times itself certainly helped by placing a mention of the exhibi- tion on its front page along with a big colour photograph of crowds gaping at a van Gogh self-portrait. If that isn't a first for an art exhibition, it is at least very unusual treatment.

But one cannot help suspecting that a large measure of cynicism went into the organisation of this exhibition. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is closed for renovation from September 1998 to the spring of 1999. Ergo, a lacklustre portion of its collection, spiced up with a few memo- rable pictures, is sent to the United States to collect some rent. (The exhibition opens at the Los Angeles County Museum on 17 January.) Maybe this doesn't matter. Maybe the public doesn't care whether the van Goghs that they are presented with as 'master- pieces' are mostly journeyman pictures. Maybe the only thing that really matters is being in a room with pictures certifiably painted by the man who was so grotesquely unappreciated by the philistines during his lifetime, but who is now bravely champi- oned by every Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice who all own framed posters of his `Sunflowers' and 'Starry Night'. Many of us, however, will feel the nausea that van Gogh's nephew, Vincent Willem van Gogh, expressed when he recalled that, when it came to his uncle's art, 'at home it was rap- ture, rapture all the time'.

Previous page

Previous page