ARTS

Exhibitions

Their own men

Giles Auty

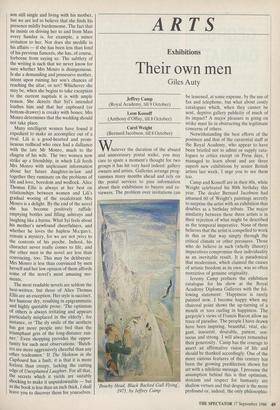

Jeffrey Camp (Royal Academy, till 9 October) Leon Kossoff (Anthony d'Offay, till 8 October) Carel Weight (Bernard Jacobson, till 8 October)

Whatever the duration of the absurd and unnecessary postal strike, you may care to spare a moment's thought for two groups it has hit very hard indeed: gallery owners and artists. Galleries arrange prog- rammes many months ahead and rely on the postal services to pass information about their exhibitions to buyers and re- viewers. The problem over invitations can

'Beachy Head, Black Backed Gull Flying', 1973, by Jeffrey Camp be lessened, at some expense, by the use of fax and telephone, but what about costly catalogues which, when they cannot be sent, deprive gallery publicity of much of its impact? A major pleasure in going on strike must lie in obstructing the legitimate concerns of others.

Notwithstanding the best efforts of the postmen and that of the curatorial staff at the Royal Academy, who appear to have been briefed not to admit or supply cata- logues to critics except on Press days, I managed to learn about and see three superb new exhibitions by senior British artists last week. I urge you to see them too.

Camp and Kossoff are in their 60s, while Weight celebrated his 80th birthday this year. The dealer Bernard Jacobson had amassed 60 of Weight's paintings secretly to surprise the artist with an exhibition that doubles as a birthday tribute. The major similarity between these three artists is in their rejection of what might be described as the temporal imperative. None of them believes that the artist is compelled to work in this or that way simply through the critical climate or other pressures. Those who do believe in such (wholly illusory) imperatives compromise their individuality as an inevitable result. It is paradoxical that modernism, which claimed the causes of artistic freedom as its own, was so often restrictive of genuine originality.

Jeremy Camp prefaces the exhibition catalogue for his show at the Royal Academy Diploma Galleries with the fol- lowing statement: 'Happiness is rarely painted now. I become happy when my charcoal point shows the up-turning of a mouth or toes curling in happiness. The gargoyle's views of Francis Bacon allow no trace of paradise. The people I have drawn have been inspiring, beautiful, vital, ele- gant, innocent, desirable, patient, sen- suous and strong. I will always remember their generosity.' Camp has the courage to assert an affirmative vision of life and should be thanked accordingly. One of the more curious features of this century has been the growing predilection shown for art with a nihilistic message. I presume the assumption behind this is that optimism, stoicism and respect for humanity are shallow virtues and that despair is the more profound or, indeed, the only philosophic-

al conclusion possible. This is a curious doctrine typical, in history, only of deca- dent and mentally lax societies.

Jeffrey Camp is a lyrical artist who has invented complex poetical structures of his own. It is odd how the strange shapes of his paintings, their unusual borders, curvings of space and perspective, symbolic juxta- positions, foreshortenings and stylistic dis- tortions all come to seem, in time, part of an obvious and convincing language. This is because all of Camp's innovations are conceived as vehicles for expression and not as ends in themselves. His paintings, like those of Kossoff and Weight, are true to their own logic; the vision is consistent. The show contains impressive early works and a good representation from his Beachy Head series. Later, slim bodies make a strange, sensual counterpoint to backdrops of London and Venice. Here are dreams and poems wherein the crusty palpability of the city contrasts with the lissom wetness of the figures. One imagines that to clasp one of these might be rather like dancing with a sea-lion.

Camp and Kossoff could hardly use paint more differently. Very thick paint, such as Kossoff uses, has come to be regarded, in recent years, as the hallmark of anguished authenticity. Kossoff and Auerbach are respected proponents of the genre but now a new generation is stepping up the impasto also, often for no good reason. Generally Kossoff's painting looks laboured and ponderous, a grim struggle for a realisation to which others respond more readily than I. The artist is recognis- ably an ex-pupil of Bomberg but has supplanted the latter's painterly finesse with a heavy-handed vehemence. Kossoff does not lack admirers, notably critics such as Peter Fuller. While liking the undoubted honesty and humanity of his intentions, I find it hard to feel personal rapport. The nature of Kossoffs vision seems to me to be closed and exclusive. His landscapes and portraits may be seen at Anthony d'Offay (9 & 23 Dering Street, W1).

Carel Weight is another artist with a very personal vision, but one which is more expansive and accessible. Throughout his career, Weight has liked ordinary people to own and enjoy his works. For years he kept the prices of his paintings low just for this reason. Who is to say, in a materialistic society, that this did not also affect notions of their aesthetic worth? Today the same paintings are being bought, for rather more, by the Saatchis from Bernard Jacob- son (2A Cork Street, W1). Now is a good time to remember that many of the paint- ings have been with us for years, to evaluate how we chose. It is worth recall- ing also that Terence Mullaly, former art critic of the Telegraph, was an early and consistent champion of Weight at a time when avant-garde art and criticism still enjoyed total ascendancy and formalist artists such as Michael Tyzack and Michael Kidner were carrying off major prizes at

the John Moores Annual. To champion Weight in those days took courage. Today it has become 'correct' at last to see in Weight's art what was apparent all along: that he creates genuine poetry from his renderings of the suburban and common- place and that he is a far more knowing and accomplished artist than many held up, over the years, for international acclaim.

As a postscript I feel obliged, by cir- cumstances, to mention a fourth superb show by a senior British artist. I have seen the splendid watercolours in John Napper's show at Albemarle Gallery (18 Albemarle Street, W1) already, since I wrote the introduction, weeks ago, for the exhibition catalogue. Thanks to the intransigence of the postmen, patrons will not have re- ceived this foretaste of the fare on view. Do not let this stop you from attending yet another feast of excellent painting.

Previous page

Previous page