So like our own dear Home life

Cressida Connolly

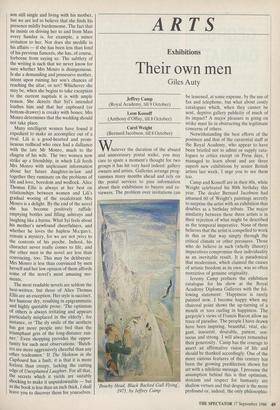

THE SKELETON IN THE CUPBOARD by Alice Thomas Ellis

Duckworth, £9.95, pp.233

Iknow people who buy The Spectator for the Home life column alone. Its weekly appearance certainly helps to make the yawning gaps between the publication of Alice Thomas Ellis' novels more bearable, although I am worried by its relentless pathos. Perhaps it is simply too like life. But surely one of that big family should notice when she is down in the dumps and offer some gesture of comfort, or at least mend her washing machine? Mrs Monro, heroine of The Skeleton in the Cupboard, is similarly surrounded by the thoughtless and the unobservant. Home life addicts will recognise her preoccupation with mor- tality and the close rapport which she enjoys with her daily, as well as the understatement and bleak wit which have become the author's trademarks.

Admirers will also recognise the plot and characters which are the same as those in her last novel, The Clothes in the Wardrobe. This time the story is told from the point of view of the mother, Mrs Monro. Put out to grass in leafy Croydon, she reflects upon a long and largely unsatisfactory life: 'I fell into the habit of sadness and gave up the practice of hope. It made existence easier. Widowed after a late and loveless mar- riage, she is preparing herself for the wedding of her only son, Syl, whose prolonged bachelorhood has become an embarrassment. Mrs Monro is not coy about the implications of having so old a son still single and living with his mother, but we are led to believe that she finds his presence mildly burdensome. The fact that he insists on driving her to and from Mass every Sunday is, for example, a minor irritation to her. Nor does she meddle in his affairs — if she has been less than fond of his previous fiancees, she has, of course, forborne from saying so. The subtlety of the writing is such that we never know for sure whether Mrs Monro is disingenuous. Is she a demanding and possessive mother, intent upon ruining her son's chances of reaching the altar, or not? Whichever she may be, when she begins to take exception to the current nuptials it is with ample reason. She detects that Syl's intended loathes him and that her cupboard (or bottom-drawer) is creaky with bones; Mrs Monro determines that the wedding should not take place.

Many intelligent women have found it expedient to make an accomplice out of a rival. Lili is a good-hearted and prom- iscuous redhead who once had a dalliance with the late Mr Monro, much to the chagrin of his wife. The two women now strike up a friendship, in which Lili feeds Mrs Monro with unpleasant information about her future daughter-in-law and together they ruminate on the problems of life and love, boredom and wedlock. Alice Thomas Ellis is always at her best on relationships between women and Lili's gradual wooing of the recalcitrant Mrs Monro is a delight. By the end of the novel she has become positively raffish: emptying bottles and filling ashtrays and laughing like a hyena. What Syl feels about his mother's newfound cheerfulness, and whether he loves the hapless Margaret, remain a mystery, for we are not privy to the contents of his psyche. Indeed, his character never really comes to life, and the other men in the novel are less than convincing, too. This may be deliberate: Mrs Monro is less than convinced by men herself and her low opinion of them affords some of the novel's most amusing mo- ments.

The most readable novels are seldom the best-written, but those of Alice Thomas Ellis are an exception. Her style is succinct, her humour dry, resulting in epigrammatic and highly quotable prose: 'The optimism of others is always irritating and appears particularly misplaced in the elderly', for instance, or 'The sly smile of the aesthete has got more people into bed than the triumphant grin of the long-distance run- ner.' Even shopping provides the oppor- tunity for such neat observations: 'Butch- ers are more aggressively cheerful than any other tradesmen.' If The Skeleton in the Cupboard has a fault, it is that it is more forlorn than creepy, lacking the cutting edge of Unexplained Laughter. For all that, the secrets which it yields are suitably shocking to make it unputdownable — but as the book is less than an inch thick, I shall leave you to discover them for yourselves.

Previous page

Previous page