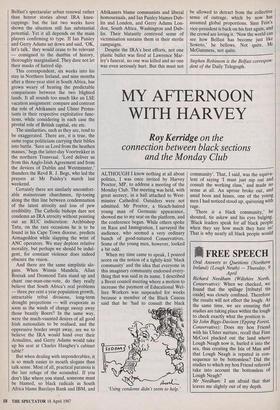

MY AFTERNOON WITH HARVEY

Roy Kerridge on the

connection between black sections and the Monday Club

ALTHOUGH I know nothing at all about politics, I was once invited by Harvey Proctor, MP, to address a meeting of the Monday Club. The meeting was held, with great secrecy, in a hall attached to West- minster Cathedral. Outsiders were not admitted. Mr Proctor, a bleach-haired young man of Germanic appearance, showed me to my seat on the platform, and the conference began. While others spoke on Race and Immigration, I surveyed the audience, who seemed a very ordinary bunch of good-natured Conservatives. Some of the young men, however, looked a bit odd.

When my time came to speak, I poured scorn on the notion of a tightly-knit 'black community' and the idea that everyone in this imaginary community endorsed every- thing that was said in its name. I described a Brent council meeting where a motion to increase the payment of Educational Wel- fare Workers was suspended for weeks because a member of the Black Caucus said that he 'had to consult the black `Using condoms didn't seem to help.' community'. That, I said, was the equiva- lent of saying 'I must just nip out and consult the working class,' and made no sense at all. An uproar broke out, and amid boos and hisses, one of the young men I had noticed stood up, quivering with rage.

`There is a black community,' he shouted, tie askew and his eyes bulging. `Black leaders speak for all black people when they say how much they hate us! That is why nearly all black people would be delighted to leave England, if only we paid their fare.'

Harvey Proctor smoothed things over with a few timely words. During the coffee break, I wandered outside and found a Catholic girl, a visitor to the cathedral, bending over an unhappy mentally hand- icapped young man, who was sitting on a wall and crying. 'No, everything is not all right,' the girl responded to my query. 'This man has been discharged from a hospital here in London and doesn't know how to get back to his house in Leeds.'

Goodness knows how long the young man had been searching for Leeds. He seemed very cold and hungry, a victim of the policy of 'returning the patient to the community'. Just more proof, if further Proof was needed, that people do not live in communities at all, but in families and in houses. I managed to smuggle the two of them into the Monday Club, and over a coffee, the girl tried to help the man to remember his address in Leeds.

I left them to it, for the meeting had recommenced. Still rejoicing in the claims of the so-called black community, the misguided Harvey Proctor was now outlin- ing his schemes for voluntary repatriation. 'And we must make sure', he cried dramatically, 'that when they're out, they stay out!'

'That's it!' a fruity voice shouted from the audience, as clapping and cheering filled the hall.

Afterwards I slipped into the cathedral, where a service was going on. What a relief to hear a different point of view. 'Love thy neighbour as thyself,' the priest proc- laimed.

Now, it appears, the black sections of the Labour Party are emulating the Mon- day Club and barring unsympathetic out- siders from their meetings. A few years ago, university activists suddenly grew tired of seeing themselves as 'the working class' and began to diversify. Some de- clared themselves 'gays', others were 'women' and still others became 'blacks'. Within this Sectioneering of Socialism, further schisms arose. Some groups eschewed the Labour Party, others joined it but still insisted on a separate niche. Sectioneers now seem to be undecided whether they are fighting capitalism or their own Labour Party. One must be defeated before the other falls, the sec- tioneers feel, but they aren't sure which to attack first. Compared to the once- formidable but secretive communist sec- tion of the Labour Party, the. new sec- tioneers are a model of integrity.

Universities and trade unions have been the twin pillars of English socialism, if something that cannot be satisfactorily defined can have a pillar. I believe that the flight from classifying mankind into capi- talists and workers can be blamed on the uncouth and boorish manners of so many trade unionists. University socialists grew to dislike the working class, seeing them as a community of Sun readers who oppres- sed heroic 'blacks, women and gays'.

West Indians have a far better reason to dislike trade unionists than a mere change in fashion. Organised labour is never so organised as when it is keeping immigrants and their children out of work. How many coloured people work in the mines, the docks or at the printing presses? The only miracle is that some join the Labour Party, let alone the black sections.

Neil Kinnock, a Welshman, shares a tradition of wild and wonderful pulpit oratory with most West Indians. Kinnock's taste in music may give us a clue to his personality. He claims to enjoy the rock and roll songs he grew up with in the Fifties, with their choruses of 'Be bop a lula' and 'A wop bop a loo boo'. Obviously he is a Teddy Boy. It is a characteristic of aging Teds to feel very self-conscious about going bald. Tap a Ted on his bald spot and he will whirl round and 'nut' you in the face with his forehead. Such behaviour is not unike the private life of Neil Kinnock. Ted Heath was bad enough, but a real Ted might be worse.

Do we want a Ted for a prime minister? If so, we must vote Labour, whether from black sections or otherwise.

Previous page

Previous page