ALL PART OF THE GAME

John Simpson defends the BBC against

a muttering campaign from the fringes of the Conservative Party

I CLIMBED out of the car, my legs cramped after being driven at 110 mph down the Al from Huntingdon. We had been determined to get to Smith Square ahead of John Major. It was 4.46 in the morning; during our journey the general election of 1992 had been won and lost. Conservative Central Office was ablaze with light, and the air was full of balloons and flags. Crowds swayed backwards and forwards, camera lights picking out small groups of happy people in the darkness. There was chanting from a group of tough- looking characters near the massed televi-

sion cameras: 'Privatise the BBC!'

It seemed a popular opinion that night. The Sunday Express journalist Bruce Anderson, often mistaken for a Conserva- tive Central Office press officer, was heard to describe the way in which the BBC would now be dismembered — as though he were a 17th-century judge sentencing a regicide. Kenneth Baker expressed his anger at the BBC's election coverage and threatened revenge. In the hallway of Cen- tral Office a hundred cameramen and photographers jostled and sweated, wait- ing for John Major's arrival. I could still

hear the chant drifting in through the open doors: 'Privatise the BBC!' Doesn't sound too good,' said one of my colleagues, like an explorer listening to the noise of drum- ming in the jungle.

There was no shortage, certainly, of peo- ple in the upper reaches of the Conserva- tive Party who felt angry with the BBC. There were new complaints about its elec- tion coverage and old ones about the Today programme, and there was the little matter of my daring to call John Major's first public meeting 'tame'. There was annoyance, too, that during the run-up to the election the 9 O'Clock News should have led with three minutes of a Neil Kin- nock speech before dealing with a John Major one; as though the Tories were Ger- man holiday-makers who had put their towel on the first place in the news bul- letins every day. Perhaps the complaint referred to the Tuesday night before polling day, when the Conservatives man- aged to let their final, climactic rally over- run and Mr Major failed to finish his speech until 9.06. As if they were a Victori- an duke at a railway station, the critics seemed to think that the BBC should have held the news until they were ready to board it.

If you are the governing party of the country and face the possibility of losing an election, little things like these mean a lot. The BBC had powerful enemies at the top of the party: of those in Mr Major's previ- ous Cabinet who would probably like to see the BBC dismantled, one, Mr Kenneth Baker, is now out of the action. But two other remaining senior Cabinet ministers share the former Home Secretary's view. Yet as I stood in the hallway of Central Office in the early hours of last Friday morning I could not believe that serious politicians would use trivial complaints as an excuse for breaking the world's best- known broadcasting service on the wheel and distributing its reeking quarters around the country.

We have, after all, been here before. Mrs Thatcher gave the impression of being a greater enemy of the BBC than anyone; yet she had a clear understanding of the way the British public felt about it. At the G7 summit in Venice she stupefied the foreign journalists who attended her final news conference by launching into a long attack on the BBC. Afterwards, as we walked together to the television interview room, I started to defend it. She stopped and laid her hand on my arm, smiling (she was warmer and less imperial in those days), and the security men behind us can- noned into one another in surprise. 'My dear, you are sensitive,' she said soothing- ly; and then, in a lower voice which I had to strain to hear, 'Don't you see it's all part of the game?'

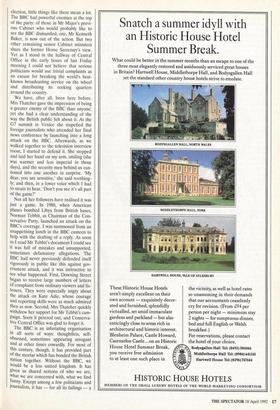

Not all her followers have realised it was just a game. In 1986, when American planes bombed Libya from British bases, Norman Tebbit, as Chairman of the Con- servative Party, launched an attack on the BBC's coverage. I was summoned from an unappetising lunch in the BBC canteen to help with the drafting of a reply. As soon as I read Mr Tebbit's document I could see it was full of mistakes and unsupported, sometimes defamatory allegations. The BBC had never previously defended itself vigorously in public like this against gov- ernment attack, and it was instructive to see what happened. First, Downing Street began to receive large numbers of letters of complaint from ordinary viewers and lis- teners. They were especially angry about the attack on Kate Adie, whose courage and reporting skills were as much admired then as now. Second, Mrs Thatcher quickly withdrew her support for Mr Tebbit's cam- paign. Soon it petered out, and Conserva- tive Central Office was glad to forget it.

The BBC is an infuriating organisation in all sorts of ways: thoughtless, self- obsessed, sometimes appearing arrogant and at other times cowardly. For most of this century, though, it has provided part of the mortar which has bonded the British nation together. Without the BBC, we would be a less united kingdom. It has given us shared notions of who we are, what we are concerned with, what we find funny. Except among a few politicians and journalists, it has — for all its failings — a real hold on the nation's affections. I do not believe public opinion would support a government if it tried to do the kind of wanton damage to the BBC that Mrs Thatcher did to independent television in Britain, ostensibly in the interests of creat- ing a more American climate in the indus- try. In America itself, the commercial broadcasting system has done nothing to raise educational standards, and as the US television networks show progressively less interest in the world outside, so the influ- ence on government policy of educated, informed opinion declines.

In Germany and France, the tone of the public service broadcasters changes when the government changes, since the jobs at the top go to people with whom the incoming government is comfortable. We do not do things this way in Britain, and the British people wouldn't like it if we did.

As for the outside world, the BBC is Britain. During the revolutions in Eastern Europe in 1988, I had only to say one worked for it to be allowed into the inner- most sanctum of the revolutionaries, to be applauded in the streets, or to be lifted, on one embarrassing occasion, over the heads of the rejoicing crowds. In Tiananmen Square the BBC was the single best-known foreigner broadcaster and we were swamped by well-wishers. During the coup in Moscow, communists and democrats alike let us do anything we wanted. Now British influence, British culture and British standards of reporting are reaching large areas of the globe through BBC World Service Television, just as they have long done by World Service radio. Within three months of its inception, the BBC's television service to Asia was said to be reaching a larger audience than the Amer- ican CNN had gained in a decade. To try to explain to such enthusiasts abroad that the ruling party in Britain has its knife into the BBC and has threatened to break it up is to invite looks of sheer incomprehen- sion.

Perhaps it will never happen. Mr Major is not a stirrer-up. He is unlikely, there- fore, to do to the BBC what Mrs Thatcher was too canny to attempt. When at the weekend Mr Major announced the cre- ation of a Department of the National Heritage, gave it responsibility for broad- casting, and put the relaxed and cultivated David Mellor in charge of it, it seemed conclusive. No doubt there will be plenty of rows before the renewal of the BBC Charter in 1996. But I believe we now have a government which appreciates that broadcasting is indeed a part of the nation- al heritage, and not something to be tin- kered with for party advantage. The advice of the revolutionary guards outside Cen- tral Office not only should be disregarded, it probably will be disregarded.

John Simpson is the BBC's Foreign Editor and a Contributing Editor of The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page