Cinema

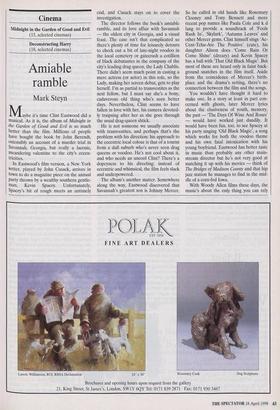

Amiable ramble

Mark Steyn

aybe it's time Clint Eastwood did a musical. As it is, the album of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil is so much better than the film. Millions of people have bought the book by John Berendt, ostensibly an account of a murder trial in Savannah, Georgia, but really a laconic, meandering valentine to the city's eccen- tricities.

In Eastwood's film version, a New York writer, played by John Cusack, arrives in town to do a magazine piece on the annual Party thrown by a wealthy southern gentle- man, Kevin Spacey. Unfortunately, Spacey's bit of rough meets an untimely end, and Cusack stays on to cover the investigation.

The director follows the book's amiable ramble, and its love affair with Savannah — the oldest city in Georgia, and a visual feast. The case isn't that complicated so there's plenty of time for leisurely detours to check out a bit of late-night voodoo in the local cemetery or gatecrash a cotillion of black debutantes in the company of the city's leading drag queen, the Lady Chablis. There didn't seem much point in casting a mere actress (or actor) in this role, so the Lady, making her screen debut, gets to play herself. I'm as partial to transvestites as the next fellow, but I must say she's a bony, cadaverous old thing who's seen better days. Nevertheless, Clint seems to have fallen in love with her, his camera devoted- ly traipsing after her as she goes through the usual drag-queen shtick.

He is not someone we usually associate with transvestites, and perhaps that's the problem with his direction: his approach to the eccentric local colour is that of a tourist from a dull suburb who's never seen drag queens or voodoo. He's not cool about it, and who needs an uncool Clint? There's a dopeyness to his directing: instead of eccentric and whimsical, the film feels slack and underpowered.

The album's another matter. Somewhere along the way, Eastwood discovered that Savannah's greatest son is Johnny Mercer. So he called in old hands like Rosemary Clooney and Tony Bennett and more tecent pop names like Paula Cole and k d lang to provide a soundtrack of 'Fools Rush In', 'Skylark', 'Autumn Leaves' and other Mercer gems. Clint himself sings 'Ac- Cent-Tchu-Ate The Positive' (cute), his daughter Alison does 'Come Rain Or Come Shine' (dreary) and Kevin Spacey has a ball with 'That Old Black Magic'. But most of these are heard only in faint back- ground snatches in the film itself. Aside from the coincidence of Mercer's birth- place and the drama's setting, there's no connection between the film and the songs.

You wouldn't have thought it hard to make one. In a story at least in part con- cerned with ghosts, later Mercer lyrics about the elusiveness of youth, memory, the past — 'The Days Of Wine And Roses' — would have worked just dandily. It would have been fun, too, to see Spacey at his party singing 'Old Black Magic', a song which works for both the voodoo theme and his own fatal intoxication with his young boyfriend. Eastwood has better taste in music than probably any other main- stream director but he's not very good at matching it up with his movies — think of The Bridges of Madison County and that hip jazz station he manages to find in the mid- dle of a corn-fed Iowa.

With Woody Allen films these days, the music's about the only thing you can rely on. A few years back, the New York Times ran a fawning profile of Allen and Mia Far- row at home in which the author, Eric Lax, explained that, even though they main- tained apartments on separate sides of Cen- tral Park, Woody was much closer and far more involved with Mia's kids than most live-in dads. This proved to be true: a few months later Mia came across the porno- graphic pictures Woody had taken of her daughter. For the next few films, Woody staggered on in his familiar role as the Lov- able Schnook. Not until now has he realised how ludicrously untenable this persona is and determined upon a mid-life career change. So, in Deconstructing Harry, Allen recasts himself as Harry Block, a foul- mouthed, sex-crazed, emotionally-barren shit who abuses and cheats on his women and then recycles their relationships in his cheesy writing. Before Harry, flatly an on- screen profanity had crossed Allen's lips. Suddenly, it's all 'fuck' and `blowjob'.

On the surface, Allen seems to be offer- ing a kind of scabrous, ruthlessly exposed honesty. But in practice the Dirty Old Man act is just a new cover for getting his increasingly woozy, feeble body into bed with young chicks. He starts the film by getting oral sex from America's television sweetheart, Julia Louis-Dreyfus (from Sein- feld), before moving on to Demi Moore and Elisabeth Shue: in other words, busi- ness as usual. It's like The Blowjob of Dori- an Gray: the gals are getting younger and younger, the gags are older and lamer than ever. If only for the sake of his comedy, next time round he should try bedding a woman of his own age (or at least within a quarter-century).

Previous page

Previous page