Arts

The sound of music

Giles Gordon

42nd Street (Theatre Royal, Drury Lane) Bashville (Open Air Theatre, Regent's Park)

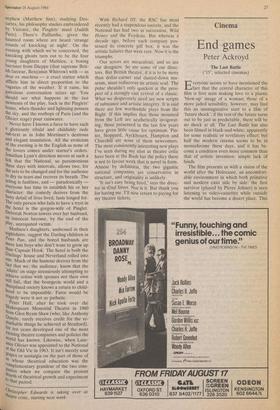

David Merrick's 42nd Street is a show which should unsettle anyone who believes that 'the musical' is an essential part of theatre. Mr Merrick is an impre- sario, not a writer or composer, and 42nd Street, in 1980, was his 84th Broadway production. It's staged expensively and vulgarly at Drury Lane with designs, by Robin Wagner, of astonishing ugliness. The story is the one, yet again, about the little girl from Provincialtown, USA (Peg- gy Sawyer, presumably a descendant of Tom) whose 'dream is to tread the boards but is so ,petrified that she stands outside the stage door of the 42nd Street Theater, New York City and misses the auditions. In spite of this, naturally, she saves the show on opening night and becomes a big star. Yuck.

If you play the record of the Broadway production as many times as I have, the music (Harry Warren) and lyrics (Al Dubin) become anodyne, even half- rememberable. The story and dialogue remain grotesque. James Laurenson plays Julian Marsh, the show's obsessed and brutish director, and he seems mildly uninterested in the proceedings. He also appears to be conspiring with the audience that it should laugh at the corn and kitsch of the lines rather than with them. But Mr Laurenson is an intelligent actor. Georgia Brown sings darkly as the displaced star, Dorothy Brock; and Margaret Courtenay brings presence and character to the show's co-author, Maggie Jones. Clare Leach, who may well become a star, dances and sings nicely as Peggy. There's loads of tap dancing and a splendidly drilled chorus of pretty gals. Lucia Victor has redirected A Little Hotel on the Side (National: Olivier)

'All right, I'm mad about you too.'

Gower Champion's Broadway production. Marsh refers to 'the tinsel and glitter of musical comedy', and the audience purrs. But this hard, cynical concoction, derived from the 1933 movie, is less about theatre and showbiz than success. The set for one of the best-known numbers, 'We're in the Money', features the Manhattan skyline constructed of dollars.

A more agreeable time may be spent, subject to weather, at Bashville, 'the new Bernard Shaw musical', adapted by David William and Benny Green from Shaw's play which, in turn, derived from his novel Cashel Byron's Profession. That profession is the noble art, and Peter Woodward, with gleaming torso, plays the well-born pugilist with wit and good humour. Felicity-Jane Goodson is Lydia Carew (almost a Lan- guish), the heiress who first encounters him, on her estate in Wiltshire, doing press-ups: 'Who are you? I take you for a god — a sylvan god.' Clearly they are destined to get together. Equally clearly, he must relinquish his brute occupation, and his pedigree be discovered. ('Worse to come, my mother is an actress.') Police- men throw down leafy screens, the foot- man Bashville (Richard Rees), who als° loves Lydia, proves a superior boxer to Byron, a Zulu completes a Shakespeare quotation, songs suggest G & S, and Benny Green contrives to insert a large number of the titles of Shaw's plays into his cod- Shakespeare lyrics. The band in the band box is jolly, Tim Goodchild's sets and costumes are a delicious adornment to the tree-lined stage, and David William directs with complete command. The second most important aspect of a Feydeau farce is how the bedrooms in pct II work. For A Little Hotel on the Sale (translated by John Mortimer from L'Hotel du Libre Echange by Georges Feydeau and, let us not forget, Maurice. Desvallieres) Saul Radomsky has provided a gorgeously seedy establishment in col- ours and textures redolent of Vuillard and Kathleen Hale's lithographs for Orland° Goes Abroad. There is the inevitable assortment of doors, stairs, corridors, rooms and beds: Michael Bryant presides unctuously and buoyantly as hotel mana- ger. To the Free Trade Hotel comes the would-be adulterous bourgeoisie. There 5 Pinglet, a building contractor (Graeole Garden, dead ringer for Alec McCowen.a! Kipling, which adds to the hilarity), With Marcelle (Dinah Stabb, robed in puce, an exotic sourbet), wife of Paillardin (J°1'4 Savident), next-door neighbours of .t",,' Pinglets. There's Maxime, Paillardin nephew (Matthew Sim), studying Des- cartes, his philosophy studies embroidered by Victoire, the Pinglets' maid (Judith Paris). There's Paillardin, given the haunted room where are heard 'strange sounds of knocking at night'. On the evening with which we're concerned, the knocking ghosts turn out to be the four Young daughters of Mathieu, a boring barrister from Dieppe (that supreme Brit- ish farceur, Benjamin Whitrow) with — as dens ex machina — a cruel stutter which afflicts him in direct proportion to the vagaries of the weather. If it rains, his garrulous conversation seizes up. You should see what happens in the last moments of the play, back in the Pinglets' house, when thunder and lightning possess the sky, and the rooftops of Paris (and the Olivier stage) pour rainwater.

Never have I known a farce to have such a gloriously ribald and childishly rude sub-text as in John Mortimer's dextrous and elegant translation. All the eroticism of the evening is in the English as none of the lovers comes under starter's orders. Jonathan Lynn's direction moves at such a lick that the National, so parsimonious these days with intervals, allows two, for the sets to be changed and for the audience to dry its tears and recover its breath. The acting is faultless, and — paradoxically everyone has time to establish his or her character: the comedy derives from the fussy detail of lives lived, lusts longed for. The only person who fails to have a tryst in _the hotel is the gorgon-wife of Pinglet. Deborah Norton towers over her husband, an innocent become, by the end of the Play, unrequited victim. Mathieu's daughters, undressed in their nightshirts, suggest the Darling children in Peter Pan, and the bored husbands are more lost boys who don't want to grow up than Captain Hook. The hotel is both the Darlings' house and Neverland rolled into nne. Much of the humour derives from the fact that we, the audience, know that the adults' on stage strenuously attempting to achieve coitus with spouses not their own Will fail, that the bourgeois world and a disciplined society knows a return to child- flood to be impossible. Farce would be tragedy were it not so pathetic. Peter Hall, after he took over the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in 1960 from Glen Byam Shaw (who, like Anthony Quayle, rarely receives credit for the re- markable things he achieved at Stratford), for ten years developed one of the most exciting theatre companies and policies the world has known. Likewise, when Laur- ance Olivier was appointed to the National at the Old Vic in 1963. It isn't merely sour grapes or nostalgia on the part of those of us whose theatrical education was the ecloplementary grandeur of the two com- panies when we compare the present earth of theatrical growth and experiment t0 that period.

With Richard III, the RSC has most recently had a stupendous success, and the National has had two in succession, Wild Honey and the Feydeau. But whereas a decade ago, before each company pos- sessed its concrete pill box, it was the artistic failures that were rare. Now it is the triumphs.

Our actors are miraculous, and so are our designers. So are some of our direc- tors. But British theatre, if it is to be more than dollar-earner and dusted-down mu- seum, must rediscover its artistic soul. The pulse shouldn't only quicken at the pros- pect of a strongly cast revival of a classic. What we desperately need are new scripts of substance and artistic integrity. It is said there are few worthwhile plays from the Right. If this implies that those mounted from the Left are aesthetically invigorat- ing, those presented in the last few years have given little cause for optimism. Pin- ter, Stoppard, Ayckbourn, Hampton and Churchill are none of them newcomers. The most consistently interesting new plays I've seen during my stint as theatre critic have been at the Bush but the policy there is not to favour work that is novel in form. Almost by definition, the two gigantic national companies are conservative in structure, and originality is unlikely.

`It isn't easy being fired,' says the direc- tor in 42nd Street. Nor iS it. But thank you for having me. I'll now return to paying for my theatre tickets.

Previous page

Previous page