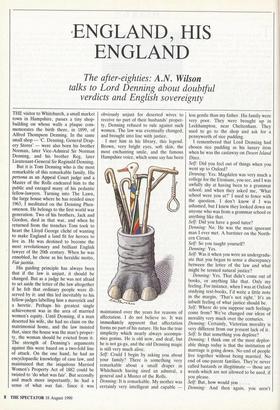

ENGLAND, HIS ENGLAND

The after-eighties: A.N. Wilson

talks to Lord Denning about doubtful verdicts and English sovereignty

THE visitor to Whitchurch, a small market town in Hampshire, passes a tiny shop- building on whose walls a plaque com- memorates the birth there, in 1899, of Alfred Thompson Denning. In the same small shop — 'C. Denning, General Drap- ery Stores' — were also born his brother Norman, later Vice-Admiral Sir Norman Denning, and his brother Reg, later Lieutenant-General Sir Reginald Denning.

But it is Tom Denning who is the most remarkable of this remarkable family. His persona as an Appeal Court judge and a Master of the Rolls endeared him to the public and enraged many of his pedantic fellow-lawyers. Turning into The Lawn, the large house where he has resided since 1963, I meditated on the Denning Phen- omenon. He belongs to the first world war generation. Two of his brothers, Jack and Gordon, died in that war, and when he returned from the trenches Tom took to heart the Lloyd George cliché of wanting to make England a land fit for heroes to live in. He was destined to become the most revolutionary and brilliant English lawyer of the 20th century. When he was ennobled, he chose as his heraldic motto, Fiat justitia.

His guiding principle has always been that if the law is unjust, it should be changed. But as a judge he was not afraid to set aside the letter of the law altogether if he felt that ordinary people were ill- served by it: and this led inevitably to his fellow-judges labelling him a maverick and a heretic. Perhaps his greatest single achievement was in the area of married women's equity. Until Denning, if a man deserted his wife, she had no claim on the matrimonial home, and the law insisted that, since the house was the man's proper- ty, the woman should be evicted from it. The strength of Denning's arguments against this were based on a two-fold line of attack. On the one hand, he had an encyclopaedic knowledge of case law, and maintained that the iniquitous Married Women's Property Act of 1882 could be twisted to 'do what was fair'. But secondly and much more importantly, he had a sense of what was fair. Since it was obviously unjust for deserted wives to receive no part of their husbands' proper- ty, Denning refused to rule against such women. The law was eventually changed, and brought into line with justice.

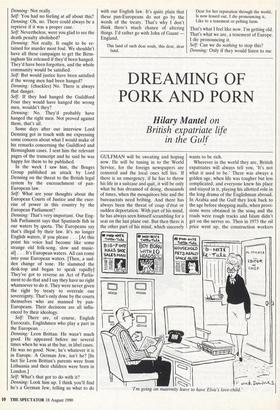

I met him in his library, this legend. Brown, very bright eyes, soft skin, the most enchanting smile, and the famous Hampshire voice, which some say has been maintained over the years for reasons of affectation. I do not believe so. It was immediately apparent that affectation forms no part of his nature. He has the true simplicity which nearly always accompa- nies genius. He is old now, and deaf, but he is not ga-ga, and the old Denning magic is still very much alive.

Self: Could I begin by asking you about your family? There is something very remarkable about a small draper in Whitchurch having sired an admiral, a general and a Master of the Rolls.

Denning: It is remarkable. My mother was certainly very intelligent and capable — less gentle than my father. His family were very poor. They were brought up in Leckhampton, near Cheltenham. They used to go to the shop and ask for a pennyworth of rice pudding.

I remembered that Lord Denning had chosen rice pudding as his luxury item when he was the castaway on Desert Island Discs.

Self: Did you feel out of things when you went up to Oxford?

Denning: Yes. Magdalen was very much a college for the Etonians, you see, and I was awfully shy at having been to a grammar school; and when they asked me, 'What school were you at?' I used to fence with the question. I don't know if I was ashamed, but I knew they looked down on anyone who was from a grammar school or anything like that.

Self: Did you have a good tutor?

Denning: No. He was the most ignorant man I ever met. A barrister on the North- ern Circuit.

Self: So you taught yourself?

Denning: Yes.

Self: Was it when you were an undergradu- ate that you began to sense a discrepancy between the letter of the law and what might be termed natural justice?

Denning: Yes. That didn't come out of books, or anything like that. Only my feeling. For instance, when I was at Oxford studying text-books, I'd write a little note in the margin, 'That's not right.' It's an inbuilt feeling of what justice should be. Self: Where do you suppose such feelings come from? We've changed our ideas of morality very much over the centuries. Denning: Certainly, Victorian morality is very different from our present lack of it. Self: Is that something you deptore? Denning: I think one of the most deplor- able things today is that the institution of marriage is going down. No end of people live together without being married. No end of one-parent families. They're never called bastards or illegitimate — those are words which are not allowed to be used, if you please.

Self: But, how would you. . . .

Denning: And then again, you aren't

allowed to talk about buggers. You must talk about homosexuality. In other words, all the words in the language which we used to condemn immorality of any de- scription have been taken out. No bas- tards, no buggers.

Self: Do you regret the change in laws relating to homosexuality? •

Denning: Oh, I don't mind 'em not being in prison, but I hate it being put on a par with other things. And lesbianism. . . . Oh no! I'm still against it.

Self: I remember that in your Dimbleby lecture, you quoted Juvenal — Quis custo- diet ipsos custodes? . . .

Denning: Yes. Who's going to guard the guardians? Who's going to guard the judges?

Self: Are you in favour of judges being called to account?

Denning: (Long pause. Laugh). That's a very nice question. They must be indepen- dent of the executive. Then, who is to call them to account? I would stress their independence.

Self: And what about a case such as that of the Guildford Four, where these men who did not commit the crimes. .

Denning: Ah!

Self: . . . are locked up for 15 years. Denning: Pause a moment. It's not true. It's not been proved against them with the strictness which English law requires. Self: Lord Denning, it has been established beyond question that the Guildford Four were not guilty of crimes for which they were imprisoned for many years.

Denning: That troubles me a lot, because I knew very well Sir Norman Skelhorn, the Director of Public Prosecutions at the time, a first-rate man. He's dead. He's unable to explain what happened, and it was his responsibility.

Self: What about Lord Donaldson? Do you think he was wrong not to appear before the May inquiry [into the conduct of the Guildford case, in which Donaldson was the original judge]?

Denning: Did they invite him to?

Self: So I understand.

Denning: I had wondered why his name was not on the list of witnesses. I think he was probably wrong to do that. Oh, yes. John Donaldson ought to have gone before the inquiry. In a way, by not doing so, the criticism is left unanswered.

Self: Exactly. And your great fear, isn't it, is that public confidence in the judiciary and the entire legal system is breaking down?

Denning: That's why I dislike television. I think they have a series called Rough Justice. Finding out cases of injustices, as they call them, thinking they're doing a lot of good.

Self: But if fresh evidence comes to light because of their investigations . . . Denning: Fresh evidence is admissible and is brought before the Court of Appeal, you see.

Self: Surely strong public confidence in the judiciary would depend on having very good judges, which we seldom seem to do. Denning: That's right. And on their being called to account when they go wrong. We haven't any system of calling them to account except by way of appeal.

Self: And is it advisable to allow anybody to serve on a jury?

Denning: That's one of the other draw- backs of recent times. In my young days, juries were all middle-aged, middle-class, middle-minded, to use Devlin's phrase. The present system of random juries may lead to random justice. Look how bad it is for these fraud cases, the Guinness trial, all that sort of thing. The jury aren't bright people, they aren't versed in accounts. Self: Are you saying that the jury system is in fact inimical to justice?

Denning: No. I've still got a firm belief in trial by jury, but I'd have them selected differently. I'd have a panel of suitable jurors. I'd let names be nominated if you please by trade unions and the like, by big employers, by the banks. In other words, I'd have a list of respectable, responsible citizens. I wouldn't have every Tom, Dick, or Harry as they do now.

Self: But do you still believe in trial by jury?

Denning: Oh, yes. Trial by jury is one of the rights of Englishmen.

Self: You mention the trade unions. You have on occasion been accused of bias against the unions.

Denning: That's quite wrong. You've got to remember the Dock Strike in 1972. Lord Donaldson, who was the President of the Industrial Court, was sending the dockers to prison and an appeal came before me. We released those dockers, and it even- tually led to the reform of the law and the Industrial Relations Act of 1971. I remem- ber one day Geoffrey Howe, who piloted that Act through the Commons, coming up to me privately and saying I'd ruined the country for the rest of the century. Because our decision torpedoed his Act.

Self: Was Geoffrey Howe a very compe- tent barrister?

Denning: I didn't think so. Had him before me quite often. He's really at heart a politician. Same as Hailsham, getting his advancement up the legal channel.

Self: Is Hailsham a great lawyer?

Denning: Oh, no. I've always known him at heart to be a politician.

Self: Do you like him?

Denning: Oh, yes, oh yes. I don't think he quite likes me. I'm not quite sure why that is. I can feel an undercurrent of envy, jealousy, whatever you like to call it. I decided it would be best to move away from such personal matters.

Self: Isn't it a terrible indictment of the legal system that barristers charge such high fees that people can't any longer afford to defend their interests in law? Denning: Yes. I've had a case recently, two people against the two archbishops . . . . Self: You issued a writ against the Archbishop of Canterbury because of his decision to ordain divorced men to the priesthood?

Denning: There's this very nice couple and she's a member of the General Synod of the Church of England. They hadn't got any money. They were against this mea- sure. I took the view, and I think they were right, it couldn't be passed except by a two-thirds majority. It was passed by less. The Archbishop ruled it was all right. Well, I drafted the writ for this couple, and a statement of claim.

Self: What was the fate of that writ? Denning: It went before the judge, Mr Justice Hoffman. He's quite a good judge but he was completely wrong about it. He torpedoed their case in half an hour and I've told them to appeal, and they are appealing. The threat against them, and this is what annoys me, is the threat of costs. They have said they won't charge the archbishops any costs if they win the case. The archbishops reply, 'Oh, ho! If we win, we're going to charge you all our costs and employ the most expensive counsel.' Using the threat of costs. I see it every day, the threat of costs being used by the big man against the little man.

Self: Do you think that was a very Christ- ian act on the part of the Archbishop? Denning: Certainly not.

Self: On the other hand, is it Christian to be a judge? 'Judge not that ye be not judged'?

Denning: I'm often asked that with regard to the death penalty. I'm about the only judge left who ever passed the death sentence.

Self: Who did you pass it on?

Denning: Oh, several people.

Self: It must have felt terrible when the black cap was put on your head.

Denning: Not really.

Self: You had no feeling at all about this? Denning: Oh, no. There could always be a reprieve if it was a proper case.

Self: Nevertheless, were you glad to see the death penalty abolished?

Denning: Not really. It ought to be re- tained for murder most foul. We shouldn't have all these campaigns to get the Birm- ingham Six released if they'd been hanged. They'd have been forgotten, and the whole community would be satisfied.

Self: But would justice have been satisfied if the wrong men had been hanged? Denning: (chuckles) No. There is always that danger.

Self: If they had hanged the Guildford Four they would have hanged the wrong men, wouldn't they?

Denning: No. They'd probably have hanged the right men. Not proved against them, that's all.

Some days after our interview Lord Denning got in touch with me expressing some concern about what I would make of his remarks concerning the Guildford and Birmingham cases. I sent him the relevant pages of the transcript and he said he was happy for them to be published.

In the week I saw him, the Bruges Group published an attack by Lord Denning on the threat to the British legal system by the encroachment of pan- European law.

Self: What are your thoughts about the European Courts of Justice and the exer- cise of power in this country by the European Parliament?

Denning: That's very important. Our Eng- lish Parliament says that Spaniards fish in our waters by quota. The Europeans say that's illegal by their law. It's no longer English waters, if you please . . . [At this point his voice had become like some strange old folk-song, slow and music- al] . . . It's European waters. All can come into your European waters. [Then, a sud- den change of tone. He slammed the desk-top and began to speak rapidly] They've got to reverse an Act of Parlia- ment to do that and I say they have no right whatsoever to do it. They were never given the right by treaty to overrule our sovereignty. That's only done by the courts themselves who are manned by pan- Europeans. Their decisions are all influ- enced by their ideology.

Self: There are, of course, English Eurocrats, Englishmen who play a part in the European Denning: Leon Brittan. He wasn't much good. He appeared before me several times when he was at the bar, in libel cases. He was no good. Now, he's whatever it is in Europe. A German Jew, isn't he? [In fact Sir Leon Brittan's parents were from Lithuania and their children were born in London.] Self: What's that got to do with it? Denning: Look him up. I think you'll find he's a German Jew, telling us what to do with our English law. It's quite plain that these pan-Europeans do not go by the words of the treaty. That's why I don't think there's much chance of altering things. I'd rather go with John of Gaunt — England,

This land of such dear souls, this dear, dear land, Dear for her reputation through the world, Is now leased out, I die pronouncing it, Like to a tenement or pelting farm.

That's what I feel like now. I'm getting old. That's what we are, a tenement of Europe. I die pronouncing it.

Self: Can we do nothing to stop this? Denning: Only if they would listen to me.

Previous page

Previous page