Exhibitions

Dynasty: The Royal House of Stewart (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

French lesson

Giles Auty

Edinburgh again and a 20-degree drop in temperature not entirely unwelcome to those who had found themselves `scun- nered' by London's recent record heat. How one welcomes the chance to wander again among the `knabs and kittoks' who assemble in equal numbers for the city's annual festivities. It is always a pleasure to be in Edinburgh but this year the city's art galleries have done us especially proud.

The National Gallery of Scotland's Ozanne and Poussin: The Classical Vision of Landscape would justify on its own a journey of greater duration than that to the east coast capital. Indeed, the 19th-century and 17th-century French masters remind us, not before time, of the rejuvenating and uplifting effect of landscape. In our own time, landscape painting has become once again one of the least considered art forms. Trendy critics of recent years have labelled the genre landescapism' and pul- led their share of cheap laughs principally from those who could not identify any five types of tree, cereal crop or butterfly correctly. The exhibition is the brainchild of Professor Richard Verdi from Birming- ham and has been brought to fruition through the generosity of General Acci- dent Assurance Corporation and a team of tireless souls led by Michael Clarke, who is employed otherwise by the National Gal- leries of Scotland. The exhibition takes place in the rather strange space set down-

stairs from the grandiose galleries of purple plush that make the National Gallery of Scotland today one of the most agreeable in the world to visit. By comparison, the special exhibition area at the rear of the building comes close to justifying the local description `nippie. But nothing can de- tract from the varied glories of this show.

The thesis advanced examines the con- trasting personal struggles of the founder of French classicism and the master of post-Impressionism to create superior orders from perceived nature. Poussin spent much of his working life in Italy and was influenced clearly by the late Renaiss- ance masters and the great Venetians. Poussin painted slowly and in solitude without using studio assistants. His land- scapes possess a remarkable unity and intensity in consequence. They are based on the accurate observations he made of the natural world, yet these elements are balanced and idealised through harmo- nious compositions. Cezanne, too, sought order in nature, and one of the great pleasures of this exhibition is to compare the contrasting ways in which the two masters worked from the basic inspiration of landscape. Cezanne remarked once that he sought to 're-do Poussin over again according to nature'. He felt an undoubted affinity of spirit to his predecessor yet physically discovered his own great land- scape compositions rather than creating them in the studio, as Poussin did, albeit from observed elements. One will wait a long time to see a more visually arresting show than this. There are 69 works in all, some of them familiar and priceless mas- terpieces, others seldom seen and less renowned works. The logistics of request- ing loans and assembling an exhibition on

this scale are daunting. Here we should be grateful also to the lenders. Juxtapositions occur in this show which emphasise the range of both artists. In Poussin's case the two great 'Phocion' landscapes from the Walker Art Gallery and the collection of the Earl of Plymouth make an especially fascinating pairing. I was not convinced that some of the late Cezannes were as troubled or turbulent as the catalogue suggests, but this is a minor cavil about a great and memorable exhibition.

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, which goes from strength to strength in terms of presentation and enterprise, has chronicled the affairs of Scotland's and England's charismatic past rulers, the Ste- wart dynasty, in a finely executed perma- nent display of paintings and more mun- dane artefacts. Three smaller theme ex- hibitions complemented the opening of this. Helen Smailes's excellent research into the life and art of John Zephaniah Bell (1794-1883) has yet to be published. Bell was the earliest reviver of fresco painting in Britain during the 19th century and was an accomplished painter in oils also. His painting of the ninth Earl of Airlie, with Lady Clementina Ogilvy, is the most memorable of the 12 works on view and would be an adornment to a Scottish national collection. At the Royal Scottish 'Academy, Scottish paintings have been hung in historical groupings culminating, though hardly climaxing perhaps, in the present day. The pleasures of familiar portraits by Ramsay and Raeburn and of landscapes by McTaggart were spiced for me by such unfamiliar minor masterpieces as Stanley Cursiter's 'Twilight', an object lesson in the evocation of the atmosphere and colour of encroaching night.

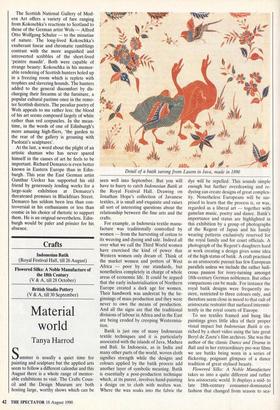

'L'Estaque, View of the Gulf of Marseilles', by Paul Ozanne The Scottish National Gallery of Mod- ern Art offers a variety of fare ranging from Kokoschka's reactions to Scotland to those of the German artist Wols — Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze — to the minutiae of nature. The long-lived Kokoschka's exuberant linear and chromatic ramblings contrast with the more anguished and introverted scribbles of the short-lived 'peintre maudit'. Both were capable of strange beauty: Kokoschka in his memor- able rendering of Scottish hunters holed up in a freezing room which is replete with trophies and slavering hounds. The hunters added to the general discomfort by dis- charging their firearms at the furniture, a popular cultural pastime once in the remo- ter Scottish districts. The peculiar poetry of Wols appeals to me rather less: the blood of his art seems composed largely of white rather than red corpuscles. In the mean- time, in the words of one of Edinburgh's more amusing high-fliers, 'the garden to the rear of the gallery is groaning with Paolozzi's sculptures'.

At the last, a word about the plight of an artistic shaman who has never spared himself in the causes of art he feels to be Important. Richard Demarco is even better known in Eastern Europe than in Edin- burgh. This year the East German artist Gunthur Uecker has supported his old friend by generously lending works for a large-scale exhibition at Demarco's threatened premises in Blackfriars Street. Demarco has seldom been less than con- troversial in his enthusiasms or less than cosmic in his choice of rhetoric to support them. He is an original nevertheless. Edin- burgh would be paler and prissier for his absence.

Previous page

Previous page