ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Face to face

Elizabeth Mortimer

Is it a painting or a person? Responses to portraits have always been ambiguous, ranging from the cherished substitute for an absent lover to the despised bread and butter of artists who yearn for the higher planes of creativity. In the hands of a great artist a portrait becomes a masterpiece, in those of your great-aunt it may eventually be an amusing period piece. There are all sorts in this exhibition at the National Por- trait Gallery, which have in common only that they have been bought with the help of the National Art Collections Fund by dif- ferent galleries around the country. The paintings, and a few busts, are numbered in roughly chronological order but hung any- how, very close together, so the effect is rather like meeting a lively assortment of people at a party. It is a complicated con- frontation: it seems as if you are looking at someone, but of course you are looking at someone who is posing for a third party, through whose eyes you also have to look. There is the question of how the sitter wishes to present himself, and how far the artist is prepared to co-operate, or whether he sees more, either for better or for worse; also of unconscious self-revelation on either part. Some artists, like Van Dyck, can ennoble their sitters. 'He took his Time to draw a Face when it had its best looks on,' said De Piles, and perhaps his cultivat- ed and charming conversation brought out the best qualities of those who sat to him.

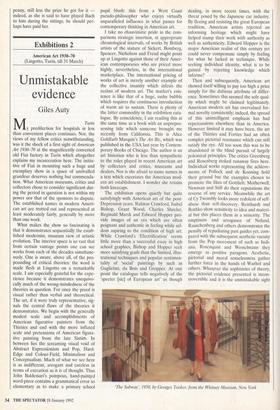

In the self-portrait the artist has full con- trol over the image he wishes to project or does he? We see Gwen John, defiant but tense with a bow at her neck and her hand on her hip. Nearby hangs her old teacher Henry Tonks, the terror of the Slade, in a small composition that is a com- pressed tour de force, but the face is wary, and very much in the shadow. Self-analysis feeds anxiety. Francis Hayman by contrast is confidently pre-Freudian: he sits before his easel, palette in one hand, knife in the other, wearing an artistic dressing-gown and velvet hat, in a gracefully turned pose looking just as an artist should, and demon- strates his powers in the elegant composi- tion, pretty colours and clever play of light and shade. This is a perfect piece of self- advertisement.

The traditional form of praise for a por- trait is that it only lacks speech to come alive. What might these people say? one wonders. Quite a few of them want us to know that they are very grand, very rich, very well educated, are making a good match or have an heir, but of course they have far too much taste to put this into words, so they resort to props — some good pictures on the wall behind them, a book in the hand, a rare tulip in an urn, .a 'Self-portrait, 1909, by Henry Tonks

rolling park or a fine mansion. The back- grounds depend partly on the intellectual climate of the time, for instance a Rousseau-inspired view of nature in the 18th century, partly on easily recognised status symbols, such as the classical pillar or balustrade and the swag of rich drapery hitched up with a heavy tassel, and partly on the painter's personal interests. Hence Reynolds paints Mrs Thomas Riddell walk- ing in reflective mood along a woodland path, while away in the distance is a watery landscape closely reminiscent of Rubens's 'Landscape by Moonlight', which Reynolds both admired and owned. Other portraits, less allusive, are designed to record the sit- ters' interests, whether globe-trotting in the cause of science, like Sir Joseph Banks (again by Reynolds, who is much in evi-

dence here), or collecting antique sculpture like Charles Towneley (Zoffany), or geolo- gy, like Dr James Hutton in the brilliant early portrait by Raeburn, where he sits, the original egghead, as composed and quiet as the fossils on the table beside him.

This sort of thing comes close to genre painting, as do the many enchanting small conversation pieces so much admired in the mid-18th century. It is clear from the works of Zoffany or Devis that conversa- tion does not necessarily involve communi- cation. Not one of the animated glances of the seven members of the Bradshaw Family meets another, while if the lady in 'The Duet' does not look round she will drop the music her partner holds out for her to take. Portraits have always been used to record appearances and provide a memori- al that cheats the grave, explicitly so in the painting of 'Sir Thomas Aston at the Deathbed of his Wife' (1635). Here, with many sad emblems, the lady lies dead on her pillows, but appears again as she was in life in the bottom right-hand corner, dressed in mourning for herself and the child who cost her her life. Latin inscrip- tions attest to the learning of artist and sit- ter, and as the centuries progressed great efforts were made to raise the status of portraiture from a lower gefire to a grand one, and the painter of heads from crafts- man to artist. This happened sooner in Britain than on the Continent, and the struggle was supposedly won when Reynolds combined classical, 'timeless' poses with elaborate life-sized composi- tions. Shown here among others of differ- ent centuries, needless to say they appear quintessentially of their age.

In fact it has always been possible for a portrait to be a great painting, and there are a few in this exhibition, among them Gainsborough's 'Morning Walk'. As well as revealing a subtle understanding of charac- ter and an assured technique, the artist sus- tains our interest over the entire surface of the canvas, suffusing all parts of the image with an indefinable poetic atmosphere. As the husband transfers his weight to his left leg, his wife remains half a pace behind and so they move in perfect counterpoise, pro- gressing obliquely towards the viewer, gaz- ing away to the right as if alone and unaware of being watched. Turn half round from this ethereal and exquisite picture and you get a jarring shock. Hanging before you is the appalling Madame Sug- gia, a cellist who apparently does not know how to press the strings, though her profile is striking. She was painted by Augustus John in a cheaply sensational vein and a red dress whose folds are so clumsily and crudely done that he did not deserve a penny, still less the prize he got for it indeed, as she is said to have played Bach to him during the sittings, he should per- haps have paid her.

Previous page

Previous page