Exhibitions

Richard Hamilton (Tate Gallery, till 6 September) Philip Braham (Raab Gallery, till 8 August)

Sixties sage

Giles Auty

Richard Hamilton, a founding father of Pop Art and friend of the Beatles, is 70 now, yet lives not in a yellow submarine but in a fine house with grounds in beautiful countryside. One feels the profession of artist has been kind to him. Currently he is also enjoying his third retrospective at the Tate Gallery, an honour accorded to few if any other artists. Photographs in the cata- logue for ,the exhibition show him in the company of such renowned cultural gurus of our time as Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol and Paul McCartney. The catalogue describes him confidently as a 'key figure in 20th-century British art'.

He has also exerted considerable influence on art education in Britain, the legacy of which continues to haunt us. That he is an extremely popular figure with the modern museum hierarchy in Britain cannot be in doubt, even without the eulogistic excesses of Richard Morphet, keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate, whose heights of enthusiasm revealed in the main catalogue essay may well leave others gasping besides himself. All this might be fine, of course, if it were aimed simply to celebrate some- thing hard to quantify, such as Andy Warhol's intelligence or Joseph Beuys's charisma. But the current trumpetings at the Tate surround a physical body of work which critics and public can see for them- selves. This is when such puffery may be judged more harshly. The late Peter Fuller, one of a very small number of critics to have written any sense about art during the past 20 years, reserved much of his store of venom for the art of Richard Hamilton. Peter could be cantankerous, yet perhaps the greater part of his ire could be explained by the extremes of veneration in which Hamilton's work is held by those in our museum service. Indeed, this last aspect may seem as mystifying to visitors as it might be to me were I not able to call upon a complete explanation of the matter provided in 1971 by the leading American critic Hilton Kramer:

but Realism was precisely what curators

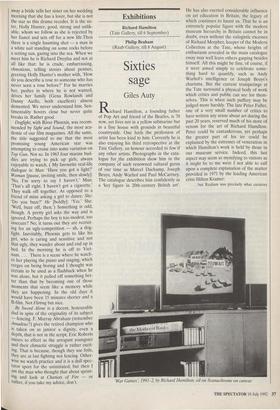

War Games', 1991-2, by Richard Hamilton, oil on Scanachrome on canvas

could not bring themselves to countenance. Realism had always stood ... for counter- revolution. Realism is what they gave up an interest in when they took their professional vows ... They might gingerly accept this or that manifestation at the fringe of the dread phenomenon — especially if, in either form or content, it was sufficiently attached to kitsch, and thus assimilable, even if distantly, to a taste formed on the conventions of Pop Art.

While doing everything in their consider- able power to frustrate a counter- revolution and any return to more authen- tic artistic values, museum curators of a modernist persuasion were also searching desperately for an art which they could claim as a valid continuation of the great tradition — but with a modernist twist. Indeed, it is argued by them now that Hamilton 'has reshaped for his own age the established categories of Western art — portraiture, landscape, still life, the interior and above all the kind of figure painting that used to be known as "history" or "high art".' To address a subject is one thing, to do so with artistic conviction and success another. Hamilton's work is based for the most part on photography and techniques more familiar to the advertising industry and commercial illustration; largely as a result, it is often thin, weak and unconvinc- ing. Indeed it is this very visual feebleness which supplies the necessary modernist 'twist'. I do not regard it as Hamilton's fault that some of his flaccid Pop produc- tions have been praised immoderately by others as 'icons of our age'; he may well be as embarrassed as I am. But he alone is responsible for the jejune nature of the vision these embody. Hamilton's social arguments seem to me locked permanently at a level of sixth-form political discourse. By coincidence great hordes of secondary school children were milling about at his show at the time of my visit. I can imagine Hamilton is a great hero to them, since the 100-odd works by him on view show a won- derful variety of ways in which the real problems of being an artist can be evaded almost entirely. Why should children both- er to master traditional techniques when these can be substituted by technical sleight-of-hand? Sadly, the extraordinary status accorded to Hamilton by modern museums is probably looked on by the young as proof that all artistic tradition is worthless now and irrelevant.

I first saw Philip Braham's work five years ago in an exhibition called The Vigor- ous Imagination. His new show at Raab (9 Cork Street, W1) deals with much the same ancestral concerns: sites of Scottish battles and burials, deluges and disasters. There is real ambition and feeling in the work, as befits an artist in his early thirties. Howev- er, technique and knowledge are in shorter supply. But can we blame Braham here when these were and are so seldom taught properly, even in Scotland, due to the efforts of modernists everywhere to radi- calise art education? As a result, Braham

paints his violently romantic subject matter as best he can, with the kind of unfocused breadth associated more generally with stage painters. This week's two shows exemplify excellently what modernist med- dling has brought to our culture.

Previous page

Previous page