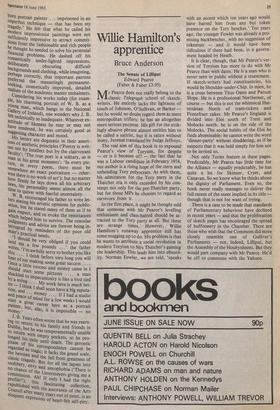

Yeats the elder

Patrick Skene Catling

Letters to his Son W. B. Yeats and Others, 1869-1922 J. B. Yeats (Seeker and Warburg £7.95)

When J. B. Yeats the Elder was in London in 1872, still learning to paint at the age of 33, while his family stayed with well-to-do in-laws in Ireland, he wrote to his wife about the 'nervous sen- sitiveness' and physical delicacy of their seven-year-old son and urged her: 'Tell Willie not to forget me.' Willie never did. He b. ecame his father's sturdiest supporter'. During the long years in which the painter never quite grasped success and the poet immense mmense in literary stature, the father became increasingly dependent and the son increasingly fatherly.

Their letters to each other are a record of

paternal deference and filial kindness. It Is difficult enough to follow a famous father; h. ow much more difficult it must be, one imagines, to be followed by a son more and more famous than oneself. J. B. Yeats s family pride and his own occasional self- abnegation were a bitter-sweet mixture; W. B. Yeats's constant dutifulness and pride of self were commendable and yet probably caused his ageing, improvident father to squirm with chagrin. J. B. spent most of the last 14 years of his life (he lived until he was 82) in a sylo- pathetic French boarding-house on the lower West Side of Manhattan. His landladies, aptly named Petitpas, were of him and evidently allowed him to rriak't. small, tip-toe forays into debt; the wine the house was cheap (the economised by not paying a liquor licence), and his fellow boarders were an ap- preciative audience at the dinner table. Ke was also a frequent guest at other tables an°, had a widening reputation as a cultivatena talked for his supper. and amusing conversationalist. He ofte Petapas.

In a letter to him in 1909, the year after J. B. had arrived in America,

'I met an American woman in London. who said to me: "Your father, we think, is the best talker in New York." ' G. K. Chester ton, on a visit to New York, met J. Brand_ wrote a letter to the New York Sun, Pts, ing him as `perhaps the best talker I evel knew.' J. B. occasionally enjoyed the _ap_

W. B. wrote°.

plause of larger audiences when he gave le; tures. They were sometimes arranged by affectionately supportive American friends' who also exerted themselves to try him to make a living as a writer of articles for magazines and as a painter of portraits. If only he had been complimented. as often

for painting as for talking about it . • • _ J. B. wrote that he believed he was a

born portrait painter ... imprisoned in an iMperfect technique — that has been my tragedy.' He felt that what he called his

Modern impressionist paintings were not sufficiently impressive to attract commis-

sions from the fashionable and rich people he thought he needed to solve his perennial

financial problems. He dashed off his romantically under-lighted impressions, deliberately obscuring difficult

backgrounds and clothing, while imagining,

Perhaps correctly, that important patrons preferred the reassuringly permanent- looking, cosmetically improved, detailed realism of the academic master embalmers. Considering his works today (for exam- ple, his charming portrait of W. B. as a

young man, which hangs in the National Gallery of Ireland), one wonders why J. B.

felt technically so inadequate. Whatever ex- actitude of likeness he may or may not have rendered, he was certainly good at suggesting character and mood. His letters are dogmatic in their assert- ions of aesthetic principles ('Poetry is writ- ten not by Intellect but by the clairvoyant faculty'; 'The true poet is a solitary, as is Man in his great moments'; 'In every pic- ture, in every poem, there must be

somewhere an exact portraiture — other- wise there is no work of art'); but no matter

how firmly he lays down all his arbitrary laws, his personality seems almost all the time to quiver with fearful uncertainty.

to rs Write let- stating his artistic opinions for public- ation, but he stated many of them as if to gain respect, and to evoke the remittances which helped him to survive. The oracular Judgments and advice are forever being in-

terrupted by reminders of the poor old M an's practical needs. 'I should be very obliged if you could lend me a fewfather writes. 'I'm awfully sorry to bother you like this .. I think before ver long you will hear of my makin y g some great success .... Once a little success and money came in I should start some pictures a man

shackled to impecuniosity is like a bird tied by a string • • . My work here is much bet- ter — I think I shall soon have a big reputa- tion, and •

and • • money , ... If I had a studio

Peace

of mind for a few weeks I would start a great career here as a portrait painter, but, alas, it is impossible — no money,'

J. B. Yeats often wrote that he was yearn- ing to return to his family and friends in Dublin, but he was temperamentally unable to return with empty pockets, so he pro- longed his exile until death. The gerontic Phase of his correspondence cannot be regarded as tragic; it lacks the grand scale, the heroism and the fall from greatness of classic tragedy But for all the lapses into snobbery, envy and xenophobia (`There is no chance of the Untermeyers giving me a com rofmission. Ah! If only I had the right Pile), this fascinating collection, republished with the assistance of the Arts Council after many years out of print, is an eloquent expression of heart-felt self-pity.

Previous page

Previous page