The end of the trail?

Christopher Brett

THE BFI COMPANION TO THE WESTERN edited by Edward Buscombe Deutsch, £19.95, pp.432 Heading west and south last summer from Denver through the Rockies and on towards the eroded sandstone wilderness that spreads across the state borders of Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mex- ico, we two codgers in the front seat were on familiar ground. Though neither of us had ever previously been within 2000 miles of this extraordinary region, we had seen it all before, that same landscape unreeling before our eyes on silver screens in the company of some hero or other, Gary Cooper maybe, or John Wayne or Clint Eastwood. In the back seat our constant commentary to this effect was met with bewilderment tinged with amused indiffer- ence by our teenage children. The Western is not part of their culture; back at home, Tor God's sake, stop it! You're drinking yourself to death'. for the first time for 50 years and more, the nursery cupboard is bare of cowboy suits, cap pistols and Indian head-dresses.

The sad statistics of the decline and fall of the Western can be examined in one of the useful appendices to this book. As long ago as 1977 only seven Western films were produced compared to over a 100 a year in the early Fifties; the decline in televised Westerns is if anything even more marked. Whether the reason is simply changing fashions and the exhaustion of overworked themes, or whether deeper forces are at work such as audience demographics, or even the end of American supremacy in the Western world, nobody really knows. It is enough that, even if only temporarily, the curtain has fallen. As Richard Schickel points out in his foreword, the very publication of this volume is a symptom of that fact; in the heyday of the Western it would have been out of date before it was printed: 'Its codification of a great screen tradition can have only one meaning: it is the signpost that marks the end of a long and lovely trail.' Be that as it may, we can celebrate with Edward Buscombe some of the richness and variety of a form of expression which will surely always be seen as a major contribution to 20th-century culture.

The book is divided into a number of sections including, besides an excellent short history of the genre written by the editor, a sizeable selection of film- and television-plot synopses/critiques and a dic- tionary of film-makers (actors, directors, producers). These are competently done but perhaps not markedly better or more comprehensively than in many a similar film encyclopaedia. The real heart and beauty of the book (and about half its content) lies in a long alphabetical section on the culture and history of the Western.

Here there is, rightly, no harping on the well known and well documented historical inaccuracies of Western films; here the concern is more with the origins and nature of the myth itself. There are longish essays on dominant Western themes such as the frontier, violence, the landscape, masculin- ity, the role of women and on determining economic factors such as the railroads, mining and agriculture. As is almost inevit- able in an encyclopaedia, the quality of the contributions is somewhat uneven and there are cases where the argument seems to have become tendentious and even pretentious. But these longer essays are interspersed with delightful shorter vign- ettes on historical characters, plot devices (the feud, the quest for revenge, the fist fight) and stock figures (the gambler, the tart, the old-timer, the drunken doctor). The only major weakness is that the cross-referencing system does not extend to identifying these cultural and historical references against the films in which they are relevant. For instance, in reading the synopsis of a film like Soldier Blue it would be helpful to be referred to the fascinating article on captivity narratives, which in fact contains a more detailed analysis of that film.

The book is splendidly illustrated on every page, with stills from films and film-making, maps (not its strongest point) and, most evocative of all, a selection of photographs and paintings of the real Old West.

If the filming of Westerns has really come to an end, then this book will make an excellent epitaph. But as one reads it, one is struck more than once by the surprising fact that although so many stor- ies of the Old West have been told and re-told many times, other good stories have never been filmed at all. What of Jedediah Smith, mountain man and explor- er, the first white man to reach California overland from the East by way of the Great Salt Lake, the Colorado River and the Mojave Desert, eventually killed by Com- anches on the Santa Fe trail? Or the Donner party, emigrants from Missouri, who fatally miscalculated their summer trek, got snowed in amidst the high Sierras, began to starve and finally to eat their dead companions (only their Indian guides re- fusing to become cannibals and being shot and eaten for their pains)? The Western has been dead and buried only to be miraculously resurrected several times already. Could it happen again? I don't see why not. There are still tales to be told and still waiting out there is the finest film set in the world, the sun still beating down, the colours still burning and blurring those endless panoramas, everything virtually unchanged from the day D. W. Griffiths first set up his cameras in the desert just a few miles from his new studios on the California coast.

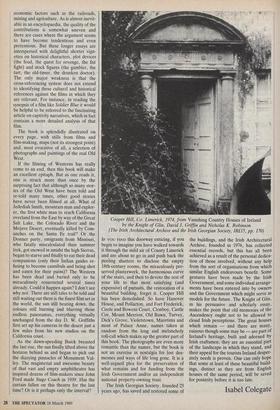

As the dawn-speeding Buick breasted the last rise, the sun finally lifted above the horizon behind us and began to pick out the dizzying pinnacles of Monument Val- ley. The magisterial and awesome beauty of that vast and empty amphitheatre has inspired dozens of film-makers since John Ford made Stage Coach in 1939. Has the curtain fallen on this theatre for the last time? Or is it perhaps only the interval? Cooper Hill, Co. Limerick, 1974, from Vanishing Country Houses of Ireland by the Knight of Gin, David J. Griffin and Nicholas K. Robinson (The Irish Architectural Archive and the Irish Georgian Society, 1R£15, pp. 170) IF YOU FIND this doorway enticing, if you begin to imagine you have walked towards it through the mild air of County Limerick and are about to go in and push back the peeling shutters to disclose the empty 18th-century rooms, the miraculously pre- served plasterwork, the harmonious curve of the stairs, and then to devote the rest of your life to that most satisfying (and expensive) of pursuits, the restoration of a beautiful building, forget it. Cooper Hill has been demolished. So have Hanover House, and Pollacton, and Fort Frederick, Coole and Bowens Court, Clonboy, Castle Cor, Mount Merrion, Old Bawn, Turvey, Dick's Grove, Violetstown, Maretima and most of Palace Anne, names taken at random from the long and melancholy roll-call which makes up the greater part of this book. The photographs are even more romantic than the names, but the book is not an exercise in nostalgia for lost des- mesnes and ways of life long gone. It is a well-argued plea for the preservation of what remains and for funding from the Irish Government and/or an independent national property-owning trust.

The Irish Georgian Society, founded 25 years ago, has saved and restored some of the buildings, and the Irish Architectural Archive, founded in 1976, has collected essential records, but this has all been achieved as a result of the personal dedica- tion of those involved, without any help from the sort of organisations from which similar English endeavours benefit. Some gestures have been made by the Irish Government, and some individual arrange- ments have been entered into by owners and the Government which might serve as models for the future. The Knight of Glin, in his persuasive and scholarly essay, makes the point that old memories of the Ascendency ought not to be allowed to cloud Irish perceptions. The great houses which remain — and there are many, ruinous though some may be — are part of Ireland's heritage, built and adorned by Irish craftsmen; they are an essential part of the landscape in which they stand, and their appeal for the tourists Ireland desper- ately needs is proven. One can only hope that some at least of these beautiful build- ings, distinct as they are from English houses of the same period, will be saved for posterity before it is too late.

Isabel Colegate

Previous page

Previous page