FINE ARTS SPECIAL

Exhibitions 1

Henry VIII: A European Court in England (National Maritime Museum, till 31August)

A king in perspex

Ruth Guilding learns about a Tudor court the modern way Henry VIII is the product of two dynamic personalities — a marketing man and a historian. The former is Patrick Roper, the National Maritime Museum's development director, a direct descendant of Sir Thomas More whose curriculum vitae also includes management appoint- ments with the British Tourist Board and Alton Towers. To him we owe the initial concept of this `jewel in the crown of the British Tourist Authority and English Tourist Board's nationwide programme', amassing Tudor treasures from all over the world with an insurance value of £150 mil- lion.

Such a blatantly commercial approach seems typical of the recent style of the National Maritime Museum, which achieved notoriety last year with its contro- versial `restoration' of the Queen's House at Greenwich and placed itself in the van- guard of our more market-orientated national museums by imposing admissions charges and shipping development staff off to Disneyland to garner fresh inspiration. Setting off for Greenwich with all these prejudices held firmly in mind, I was sure that not even Mr Roper's illustrious ances- tor would be able to defend him and his exhibition from a charge of the grossest vulgarity.

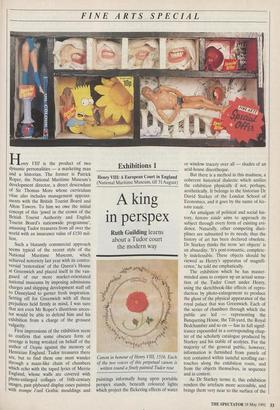

First impressions of the exhibition seem to confirm that some obscure form of revenge is being wreaked on behalf of the author of Utopia against the memory of Henrician England. Tudor treasures there are, but to find them one must wander through a maze-like chain of chambers which echo with the taped lyrics of Merrie England, 'whose walls are covered with photo-enlarged collages of 16th-century images, past plyboard display cases painted with trompe l'oeil Gothic mouldings and Canon in honour of Henry VIII, 1516. Each of the two voices of this perpetual canon is written round a finely painted Tudor rose paintings informally hung upon portable perspex stands, beneath coloured lights which project the flickering effects of water or window tracery over all — shades of an acid-house discotheque.

But there is a method in this madness, a coherent historical dialectic which unifies the exhibition physically if not, perhaps, aesthetically. It belongs to the historian Dr David Starkey of the London School of Economics, and it goes by the name of his- toire totale.

An amalgam of political and social his- tory, histoire totale aims to approach its subject through every form of existing evi- dence. Naturally, other competing disci- plines are subsumed to its needs; thus the history of art has been declared obsolete. Dr Starkey thinks the term 'art objects' is an absurdity. 'It's post-romantic, complete- ly indefensible. These objects should be viewed as Henry's apparatus of magnifi- cence,' he told me emphatically.

The exhibition which he has master- minded aims to conjure up an actual sensa- tion of the Tudor Court under Henry, using the sketchbook-like effects of repro- duction by photo-enlargement to produce the ghost of the physical appearance of the royal palace that was Greenwich. Each of the series of chambers through which the public are led — representing the Banqueting House, the Tilt-yard, the Royal Bedchamber and so on — has its full signif- icance expounded in a corresponding chap- ter of the scholarly catalogue produced by Starkey and his stable of acolytes. For the majority of the general public, however, information is furnished from panels of text contained within tasteful scrolling car- touches along the exhibition route, and from the objects themselves, in sequence and in context.

As Dr Starkey terms it, this exhibition renders the artefacts more accessible, and brings them very near to the surface of the argument. Consequently, he feels tri- umphantly vindicated when I complain that Tudor portraits look unseemly when mounted on portable perspex display stands, and their perspex glazing reduces artistic verisimilitude to the shiny texture of a photograph.

Grudgingly, it must be admitted that this radical exhibition formula seems to work. The evidence was plain — people of all types and ages browsing studiously among the display cases and assimilating information at a sophisticated level.

Thus I learned that the cosmographical ceiling delineated by Holbein in Henry's Banqueting House (and mocked up for the exhibition by means of a projector) proba- bly alerted the king to the practical applica- tions of map-making which proved so significant in the reign of his daughter, Elizabeth.

Henry's religious convictions (complex, strategic, but nevertheless sincerely held), dealt with in the Royal Bedchamber sec- tion, are illustrated by his beautifully carved rosary and the exquisite psalter cov- ered in his marginalia, illuminated by the Frenchman Jean Mallard, with representa- tions of Henry as his Old Testament hero, King David. The book is open at a vignette of private devotions in the king's bedcham- ber, above the text, `Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum. . . . '

The bed illustrated in this psalter re- appears in a lifesize photo-enlargement mounted on the wall adjacent to portraits of Henry and Anne of Cleves, while a con- fidential voice-over loop describes the humiliating non-consummation of this par- ticular royal marriage in Henry's own words. With the exception of Anne Boleyn, other wives are scarcely featured, and scarcely missed.

Doubtless there will be more exhibitions of this type. The Cambridge historian Dr Christopher Bayly employed a similar, albeit more conservative proseletysing technique for Anglo-Indian history with The Raj at the National Portrait Gallery earlier this year, and Dr Starkey's votary, the youthful Dr Simon Thurley, curator of royal palaces, plans a variety of new attrac- tions beginning with a recreation of the Great Kitchens at Hampton Court Palace later on this month.

The fogeys of the art world may throw up their hands in horror, but the modern technology of our times might as well be invested to some useful educative purpos- es. Henry VIII does not give us the old cliched portrait of its subject — 'So bluff! So burly. So truly English. Such a picture!' Instead, we have pure history, rendered into a palatable form for the appetites of a mass culture.

During Henry VIII's anniversary year there will be many local events taking their theme from Tudor times, including festivals, ban- quets, films, theatre and sports. For informa- tion, telephone 081 858 6376.

Previous page

Previous page