Theatre

Long night's journey

Kenneth Hurren

It is asking a lot of modern audiences seeing Macbeth, I have always thought, that they should believe in the witches and their supernatural powers; it is necessary only to accept that the people in the play believe in them, in the context of their• own superstitious time. Michael Blakemore, who has directed the National Theatre company in the new production of the work at the Old Vic, seems to be in two minds about this, for he has expended an inordinate amount of time on these women in a seeming effort to make their little coven plausible.

They are not at all the fantasticated, unearthly grotesques usually encountered on that blasted heath. Two of them are knocking on a bit, are inclined to be querulous and have plainly rather let themselves go (but I should not be altogether surprised to see them behind the counters of theatre bars or sub-post offices); the third is fairly young but gives the impression of having very little Upstairs, assuming for most of the time a foolish and disconcertingly vacant stare. As women they are, if not appetising, relatively credible. When we first see them, practising a little silent invultuation and looking as though they are wondering whether it is going to work, they seem merely to be coquetting experimentally With witchcraft, a notion confirmed when we find them following cook-book instructions while brewing up their spells. It is hardly conceivable that they should Possess any supernatural gifts, so the Prophetic apparitions are done away with, being replaced by ventriloquist's dolls on sticks, and the parade of kings that winds Up the scene can IA passed off as the dream-like product of the by now somewhat fevered imagination of the apprehensive thane. Blakemore is not absolutely consistent — there is one touch Of real magic, when one of the witches disappears, pfft (via a stage trapdoor), leaving her mortal clothes behind her in a heap on the floor — but there is no especial virtue in a wrong-headed consistency, and I'm afraid the general conception of the witches as mischievous eccentrics, however reasonable to contemporary spectators, is not quite what Shakespeare, primarily concerned with their impact and influence on Macbeth, was calling for.

• I have rather run on about the witches, whom I should ordinarily regard as incidental, only because the production itself makes such a point of them. The programme-book devotes sixteen of its twenty-four pages to witches (not these witches, other witches) so it is clear that someone at the National has a bit of an obsession with them; and, at curtain-rise, several minutes are determinedly allocated to their activities before a word of the text is spoken. When this elaborated opening scene is over, it is followed by another silent interpolation in which Duncan's soldiers cross the stage in slow-motion, moon-walk style (they're battle-weary, you understand), and although Macbeth is the shortest of Shakespeare's major plays, I knew then it was going to be a long night.

The trouble is, probably, that the play is so well-known that any producer these days looks upon its familiar quotations and events as a special challenge to his inventiveness. The sleepwalking scene, the ghost of Banquo at the feast, the dagger hallucination, the drunken porter, the showdown with Macduff and so on, including, of course, the witches — if these things cannot be done better than ever before, then the obligatory requirement is that they should at least be done differently. The way things have been going this year, it occurs to me that it may be innovatory enough to have the play set in ancient Scotland and performed by white people, but this is doubtless a minority, not to say frivolous, view. The present production, despite its aberrant approach to the witches, and its mildly anachronistic Elizabethan costumes, is not, in fact, spectacularly bizarre. Some of Blakemore's imaginative touches are stunningly successful. I am less than enthusiastic about his slow-motion sequence at the beginning, but his return to the same technique at the end to portray the death of Macbeth is rivetingly effective, improving distinctly upon Shakespeare's scenario in which, with a casual 'Exeunt fighting,' the protagonist's deathscene is moved uncharacteristically and anti-climactically off-stage.

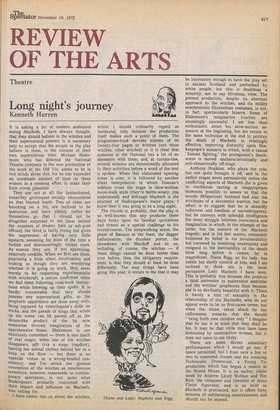

Anthony Hopkins, who plays the role, has not quite brought it off, and in the earlier stages never persuasively unites the conflicting aspects of Macbeth (he is given to vociferous ranting at inappropriate moments, possibly to assure us that the moody Milquetoast husband had also the attributes of a successful warrior, but the effect is to suggest that he is absurdly indiscreet and heedless of eavesdroppers); but he conveys with splendid intelligence the inner struggle between conscience and imagination in which, in the triumph of the latter, lies the essence of the Macbeth tragedy; and in his last scenes, ostensibly bolstered by belief in his invulnerability but cornered by mounting uncertainty and resigned to the inevitability of the death blow long before it comes, he is magnificent. Diana Rigg, as his lady, has subtle but steely control of him, and I am inclined to think she is the most persuasive Lady Macbeth I have seen. This is probably less because she projects a total surrender to malevolent ambition and the witches' prophecies than because she is so devilishly beautiful with it. There is barely a hint of sexuality in the relationship of the Macbeths, who do not appear even to be on first-name terms, but when the thane, taken aback by her callousness, remarks that she should "bring forth men children only" I imagine that he has it in mind that they shall be his. It may be that virile men have been dominated by unattractive women, but it does not seem to me likely.

There, are some decent subsidiary performances which I would go into if space permitted, but I must save a line or two to commend Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, a Young Vic production which has begun a season at the Round House. It is an earlier, jokier work by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, the composer and librettist of Jesus Christ Superstar, and is as brief as Macbeth is protracted, but it offers forty minutes of exhilarating entertainment and should not be missed.

Previous page

Previous page