Mrs Gandhi returns

Sasthi Brata

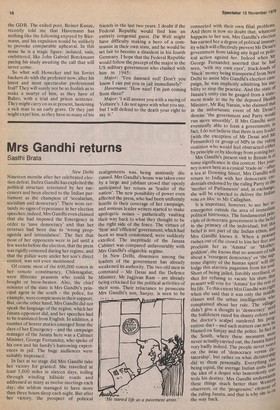

New Delhi Nineteen months after her celebrated election defeat, Indira Gandhi has exploited the political structure reinstated by her successors and been elected to -the Indian parliament as the champion of 'secularism, socialism and democracy'. There were certainly no signs of repentance in her election speeches; indeed, Mrs Gandhi even claimed that she had imposed the Emergency in order to 'save democracy' and that her reverses had been due to 'wrong propaganda and intimidation'. The fact that most of her opponents were in jail until a few weeks before the election, that the press was rigidly censored during her regime, and that the police were under her son's direct control, was not even mentioned.

Of course most of the 600,000 voters in her remote constituency, Chikmagalur, were illiterate peasants who could be bought or brow-beaten. Also, the chief minister of the state is Mrs Gandhi's principal agent in the south — the police, for example, were conspicuous in their support. But, on the other hand, Mrs Gandhi did not speak the language of the region, which her Janata opponent did, and her speeches had to be translated from English. In addition, a number of horror stories emerged from the days of her Emergency — and the campaign manager of the Janata here was a Cabinet Minister, George Fernandez, who spoke of his own and his family's harrowing experiences in jail. The huge audiences were suitably impressed.

In fact at no stage did Mrs Gandhi take her victory for granted. She travelled at least 5,000 miles in sixteen days, toiling through winding hillside roads and addressed as many as twelve meetings each day; she seldom managed to have more than three hours sleep each night. But after her victory, the prospect of political realignments was, being anxiously discussed. Mrs Gandhi's house was taken over by a large and jubilant crowd that openly anticipated her return as 'leader of the nation'. The new possibility of power even affected the press, who had been uniformly hostile in their coverage of her campaign, and anxious leader writers started to make apologetic noises — pathetically vaulting their way back to what they thought to be the right side of the fence. The virtues of 'firm' and 'efficient' government, which had been so much condemned, were suddenly extolled. The ineptitude of the Janata Cabinet was compared unfavourably with Mrs Gandhi's oligarchic regime.

In New Delhi, dissension among the leaders of the government has already weakened its authority. The two old men in command — Mr Desai and the Defence Minister, Mr Jagjivan Ram — are already being criticised for the political activities of their sons. Their reluctance to prosecute Mrs Gandhi's son, Sanjay, is seen to be connected with their own filial problems. And there is now no doubt that, whatever happens to her son, Mrs Gandhi's election has earned her a degree of political immurlity which will effectively prevent Mr Desafs government from taking any legal or pobt" ical action against her. Indeed when Mr George Fernandez asserted that he had seen, 'with my own eyes', truck-loads of 'black' money being transported from New Delhi to assist Mrs Gandhi's election canr paign, he was implicitly admitting his inability to stop the practice. And the state of Janata's unity can be gauged from a statement made to me by the deposed Health Minister, Mr Raj Narain, who claimed that in the unfortunate event of Mr Desai s demise 'the government and Party would run more smoothly'. If Mrs Gandhi were eventually able to form a government, fact, I do not believe that there is any leader (with the exception of Mr Desai and l'Ar Fernandez) or group of MPs in the ruling coalition who would feel obstructed either by principle or by ideology from joining her; Mrs Gandhi's present visit to Britain is °I some significance in this context. Her jour" ney is seen here as a cynical 'trade-in' —after, a tea at Downing Street, Mrs Gandhi 011 return to India with her democratic credentials endorsed by the ruling Party in the 'mother of Parliaments' and, in exchange' she will be expected to deliver the Indian vote en bloc to Mr Callaghan. It is important, however, to see her.re" emergence outside the area of iminedla.te political histrionics. The fundamental cipie of democratic government is the belle... in the primacy of the individual; but thl; belief is not part of the Indian ethos, all Mrs Gandhi knows it. When a peasanA rushes out of the crowd to kiss her feet a11'. proclaim her as 'Amma' or 'mother: goddess', she knows that no amount of tali' about a 'resurgent democracy' or 'the Sur reme dignity of the human spirit' will dIsi lodge this atavistic paganism from his sc/t1; Short of being jailed, forcibly sterilised, °t shot for refusing to vacate his slum Olaf peasant will vote for 'Amma' for the reSt his life. To this extent Mrs Gandhi was 001 when she said that it was only the middle classes and the urban intelligentsia wilt!. complained about her rule. The villa didn't give a thought to 'democracy' Ott] the bulldozers razed his shanty colony all the doctor's scalpel sundered his prt enitive duct — and such matters can now in blamed on Sanjay and the police. In fact re the South, where these measures vv.e'A never actually carried out, the Janata fairedv very badly indeed. The people never vo,te.c, on the issue of 'democracy versus tatorship', but rather on what dictatorshislYe did to them personally. Everything being equal, the average Indian quite the idea of a despot who benevolently e°t,s trots his destiny. Mrs Gandhi understat these things much better than wester "of observers, or the 'progressive' elemerl, t the ruling Janata, and that is why she is the way back.

Previous page

Previous page