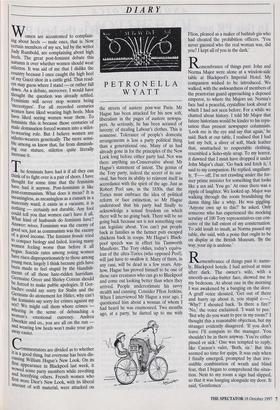

DIARY

PETRONELLA WYATT Women are accustomed to complain- ing about heels — male ones, that is. Now certain members of my sex, led by the writer Judy Rumbold, are complaining about high heels. The great post-feminist debate this autumn is over whether women should wear Stilettos It was aid of me that I dislike the country because I once caught the high heel of my Gucci shoe in a cattle grid. Thus read- ers may guess where I stand — or rather fall down. As a debate, moreover, I would have thought the question was already settled. ,Ferninism will never stop women being stereotypes'. For all recorded centunes women have liked wearing high heels. Men have liked seeing women wear them. To feminists this is because those centuries of male domination forced women into a stilet- to-wearing role. But I believe women are stiletto-wearers genetically. The more sensi- ble among us know that, far from diminish- lug our stature, stilettos quite literally increase it.

he feminists have had it if all they can think of to fight over is a pair of shoes. I have thought for some time that the feminists have had it anyway. Post-feminism is like Post-communism. What does it mean? It is meaningless, as meaningless as a eunuch in a maternity ward; it exists in a vacuum; it is uuthing — certainly not durable. Any fool could tell you that women can't have it all. What kind of husbands do feminists have? Answer: wives. Feminism was the enemy of good sex, just as communism was the enemy of a good income. The feminist fronde tried to conquer biology and failed, leaving many women feeling worse than before it all began. Suicide rates among young women have risen disproportionately to those among Young men, largely I think because girls have been made to feel stupid by the blandish- ments of all those hate-ridden harridans. Germaine Greer and Shirley Conran should be forced to make public apologies. If Gor- bachev could say sorry for Stalin and the Germans do atonement for Hitler, why can't the feminists say sorry for crimes against my sex? We might call them whore crimes — whoring in the sense of debauching a woman's emotional currency. Andrea Dworkin and co., you are all on the run — and wearing low heels won't make your get- away easier.

C . . onunentators are divided as to whether it is a good thing, but everyone has been &- cussing William Hague's New Look. On its first appearance in Blackpool last week, it wowed some party members while revolting and horrifying others' French women who first wore Dior's New Look, with its liberal amount of soft material, were attacked on the streets of austere post-war Paris. Mr Hague has been attacked for his new soft, liberalism in the pages of austere newspa- pers. As seriously, he has been accused of larceny; of stealing Labour's clothes. This is nonsense. Tolerance of people's domestic arrangements is less a party political thing than a generational one. Many of us had already gone in for the principles of the New Look long before either party had. Nor was there anything un-Conservative about Mr Hague's statement of intent. The genius of the Tory party, indeed the secret of its sur- vival, has been its ability to reinvent itself in accordance with the spirit of the age. Just as Robert Peel saw, in the 1830s, that the Tories must embrace the idea of political reform or face extinction, so Mr Hague understood that his party had finally to acknowledge a sexual freedom on which there will be no going back. There will be no going back because sex is not something one can legislate about. You can't put people back in families as the farmer puts escaped chickens back in coops. Mr Hague's Black- pool speech was in effect his Tamworth Manifesto. The Tory oldies, today's equiva- lent of the ultra-Tories (who opposed Peel), will just have to swallow it. Many of them, in any case, will be dead in a few years. Any- how, Hague has proved himself to be one of those rare creatures who can go to Blackpool and come out looking better than when they arrived. People underestimate his savvy stealth and cunning. Consider Ffion Jenkins. When I interviewed Mr Hague a year ago, I questioned him about a woman of whom I had heard he was enamoured. Two months ago, at a party, he darted up to me with Ffion, pleased as a maker of bathtub gin who had cheated the prohibition officers. 'You never guessed who the real woman was, did you? I kept all of you in the dark.'

Remembrance of things past: John and Norma Major were alone at a window-side table at Blackpool's Imperial Hotel. My companion wished to be introduced. We walked, with the awkwardness of members of the praetorian guard approaching a deposed emperor, to where the Majors sat. Norma's face had a peaceful, crystalline look about it which I had not seen before. For a while we chatted about history. I told Mr Major that future historians would be kinder to his repu- tation than present newspaper columnists. 'Look me in the eye and say that again,' he said. Back at our table, I realised that I had lost my belt, a sliver of soft, black leather that, unattached to respectable clothing, resembled a Soho-style strap. To my horror, it dawned that I must have dropped it under John Major's chair. 'Go back and fetch it,' I said to my companion. He replied, ungallant- ly, 'F— off. I'm not crawling under the for- mer prime minister for something that looks like a sex aid. You go.' At once there was a ripple of laughter. We looked up. Major was walking through the room brandishing the damn thing like a whip. He was giggling. 'Anyone own up to this?' he asked. Only someone who has experienced the mocking scrutiny of 100 Tory representatives can con- ceive of the full extent of my consternation. To add insult to insult, as Norma passed my table, she said, with a poise that ought to be on display at the British Museum, 'By the way, your zip is undone.'

Remembrance of things past it: name- ly, Blackpool hotels. I had arrived at mine after dark. The owner's wife, with a smooth-as-cake-batter face, showed me to my bedroom. At about one in the morning I was awakened by a banging on the door. A gruff voice shouted, 'Get out of there and hurry up about it, you stupid c—.' 'Why?' I shouted back. 'Is there a fire?' 'No,' the voice exclaimed. 'I want to pee.' 'But why do you want to pee in my room?' I thought this a reasonable objection, but my stranger evidently disagreed. 'If you don't leave I'll compain to the manager. You shouldn't be in there anyway. You're either pissed or sick.' One was tempted to reply, like Curzon's valet, 'Both, sir.' But this seemed no time for quips. It was only when I finally emerged, prompted by that irre- sistible combination of wrath and blind fear, that I began to comprehend the situa- tion. Next to my room a sign had slipped, so that it was hanging alongside my door. It said, 'Gentlemen'.

Previous page

Previous page