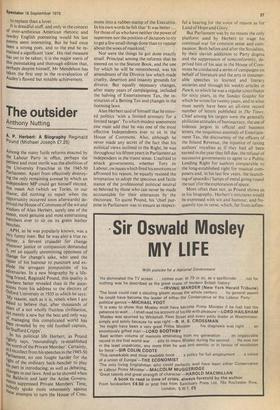

The outsider

Anthony Nutting

A. P. Herbert: A Biography Reginald PoUnd (Michael Joseph 27.25)

Among the many futile reforms enacted by the Labour Party in office, perhaps the Pettiest and most sterile was the abolition of the University Franchise in the 1945-50 Parliament. Apart from effectively destroying the only remaining avenue by which an Independent MP could get himself elected, this mean Act (which we Tories, to our shame, did nothing to repair when the • oPportunity occurred soon afterwards) dePrived the House of Commons of the wit and Wisdom of Alan Herbert, surely one of the sanest, most genuine and most entertaining th, embers ever to sit on its green leather benches.

APH, as he was popularly known, was a very funny man. But he was also a true reformer, a fervent crusader for change Wherever justice or compassion demanded It, yet an equally unremitting opponent of Change for change's sake, who used the rapier of his humour to puncture and exDiode the arrogant pomposities of his adversaries. In a new biography by a lifelong friend, Reginald Pound, this quality is nowhere better revealed than in the quotations from his address to the electors of Pxford University in 1935 in which he says: MY reason, such as it is, rebels when I am asked to believe that, after thousands of Years of a not wholly fruitless civilisation, rlot merely a new but the best and only way 131. managing this complicated world has 2een revealed by my old football captain, 4Ir Stafford Cripps'. r. In his political life Herbert, as Pound tLightlY says, 'resoundingly re-established "e worth of the Private Member'. Certainly, 4ps I recollect from his speeches in the 1945-50 r.4rhament, no one fought harder for the islITht of the ordinary back-bencher to play ells Part in introducing, as well as debating, anges in our laws. And as he showed when Baldwin and later the Attlee Governsuppressed Private Members' Time, :body spoke more vehemently against ilese attempts to turn the House of Com

mons into a rubber-stamp of the Executive. In his own words he felt that 'It was better ... for those of us who have neither the power of supermen nor the position of dictators to try to get a few small things done than to vapour abont the woes of mankind.'

Nor were the things he got done exactly small. Principal among the reforms that he steered on to the Statute Book, and the one for which he will be remembered, was his amendment of the Divorce law which made cruelty, desertion and insanity grounds for divorce. But equally necessary changes, after many years of campaigning, included the halving of Entertainment Tax, the institution of a Betting Tax and changes in the licensing laws.

Alan Herbert said of himself that he entered politics 'with a limitedarmoury for a limited target'. To which modest assessment one must add that he was one of the most effective Independents ever to sit in the House of Commons. Also, although he never made any secret of the fact that his political views inclined to the Right, he was throughout his fifteen years in Parliament an independent in the truest sense. Unafraid to attack governments, whether Tory or Labour, on issues which fired his emotions or affronted his reason, he equally resisted the temptation to adopt the specious and facile stance of the professional political neutral so beloved by those who can never be made accountable for their utterances by the electorate. To quote Pound, his 'chief purpose in Parliament was to ensure as respect

ful a hearing for the voice of reason as for Land of Hope and Glory.'

But Parliament was by no means the only platform used by Herbert to wage his continual war for common sense and compassion. Both before and after the Socialists, by their slavish addiction to Party dogma and the suppression of nonconformity, deprived him of his seat in the House of Commons he conducted a series of campaigns on behalf of literature and the arts in innumerable speeches to learned and literary societies and through his weekly articles in Punch, to which he was a regular contributor for sixty years, in the Sunday Graphic for which he wrote for twenty years, and in what must surely have been an all-time record number of letters published in The Times. Chief among his targets were the generally philistine attitudes of bureaucracy, the use of hideous jargon in official and business letters, the iniquitous anomaly of Entertainment Tax, the discourtesy of the officers of the Inland Revenue, the injustice of taxing authors' royalties as if they had all been earned in the year they fell due, the refusal of successive governments to agree to a Public Lending Right for authors comparable to the long-established right for musical composers and, in his last few years, the launching of sputniks (lumps of metal going round the sun') for the exploration of space.

More often than not, as Pound shows us in his biography. Herbert's strictures would be expressed with wit and humour, and frequently too in verse, which, far from soften ing their impact, actually sharpened the effect. (He must have been one of the very few taxpayers ever to have made out a cheque to the Inland Revenue in the form of a poem complaining about their 'UnChristian' persistence in plundering his 'dwindling earnings'.) Yet he could also, on occasion, take himself seriously, as he did when Churchill asked him during the last war whether a second good conduct badge on his Petty Officer's uniform indicated that he had been promoted or vaccinated. Not amused, he replied 'Sir, you've been First Lord of the Admiralty. You must be familiar by now with the badges of Petty Officers of the Royal Navy'.

Although he began tilting at authority in the First World War in humorous verse published in Punch, Herbert was also seriously enough affected by the monstrous slaughter at Gallipoli and in Flanders and by the brutalities of military discipline to write his first novel, The Secret Battle, about a young officer who was shot for cowardice, which Field-Marshal Montgomery described as 'the best story of front-line war' and which later helped to promote reforms and relaxations of army discipline. In a lighter vein, though with equally serious intent, he published his famous novel Holy Deadlock, an exposé of British divorce law which forced those who wanted a divorce to commit adultery whether they wished to or not. And, like The Secret Battle, this book helped to create the climate of opinion necessary to achieve the desired reform of the law—not a bad record for any novelist.

In all, Pound tells us, Herbert wrote more than seventy books and some twenty plays, musical comedies and operettas. But, whereas his books were generally successful, his theatrical ventures, in spite of backing from C. B. Cochran, seldom enjoyed a long run. Why this was, his biographer does not tell us. Nor does he tell us much about Herbert's personality, apart from an occasional reference to such eccentricities as his addiction to vitamin pills, or his capacity to concentrate amid a hubbub of noise. Rather does he let others describe him, as undoubtedly he was, as 'the ideal companion'. For a life-long friend these omissions seem strange. Stranger still was the author's decision to include two gratuitously insulting and slanderous passages in a letter about Herbert from an embittered Tory backbencher, whose contribution to the parliamentary scene was as paltry and pedestrian as Alan Herbert's was illustrious and entertaining.

Although in some passages Pound's book comes alive, notably where he describes Herbert's love of the Thames and his wartime service in his beloved 'Water Gipsy', the narrative is all too often dry, disjointed and peppered with incidents and anecdotes that seem designed solely to 'drop' some famous name. Nevertheless, it is worth reading if only because the author allows his subject to fill so many pages with his own inimitable verse, and so once more to make his readers chuckle.

Previous page

Previous page