BOOKS

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, was a toff if ever there was one. If John Prescott had been in charge Lord Salisbury would never have made it. Andrew Roberts's new biog- raphy shows just how wrong Mr Prescott would have been. Salisbury's life is one of the best arguments for aristocratic govern- ment I have read.

Salisbury was three times prime minister, but he is relatively little-known. Unlike Gladstone or Disraeli he was never the subject of a cult. Examination questions are not set on him, nor are statues erected in his memory. He hasn't even had a full biog- raphy until this year. Lady Gwendolen Cecil published four classic volumes of family biography in the 1920s but only got as far as 1891, leaving her father's last gov- ernments uncovered. Andrew Roberts fills this gap, and this will become the standard life. He was given free run of the massive Hatfield archive, and he has consulted in addition the papers of 140 politicians.

The Hatfield archive apparently contains surprisingly few skeletons, and these seem mainly to relate to Salisbury's troubled early life. Roberts rattles briskly along through Salisbury's first 44 years. Salisbury was the second son; his older brother Cran- borne was blind and an invalid. His mother died when he was nine and ,he endured a miserable, lonely childhood in spite of Hatfield's 40 indoor servants. At Eton he was a pathetic swot and weakling. He was bullied so viciously that his father eventual- ly took him away. Roberts doesn't specu- late, but Salisbury's appalling childhood surely scarred him for life.

Salisbury married at 27 a judge's daugh- ter, Georgina Alderson. Not only was she plain, intelligent and middle-class but, worse still, she brought no money. His brutish father threatened to cut him out of his will and refused to speak to him for seven years. This was the making of him. He was forced to earn his living, writing as a hack for the right-wing Saturday Review which fortunately happened to belong to his brother-in-law Alexander Beresford- Hope. He churned out two million words of journalism, perfecting a style of biting, sneering, sharp-tongued sarcasm.

When his older brother suddenly and conveniently died, followed shortly by his father, Salisbury found himself vastly rich (Roberts could usefully say a bit more about this side of things). Being a Marquess with a Jacobean palace and Tudor ancestors made him irresistible to Disraeli, who wooed him assiduously. Ignoring two decades of ill-natured anti- Semitic sniping and disloyal gossip from

Seeing Salisbury plain

Jane Ridley

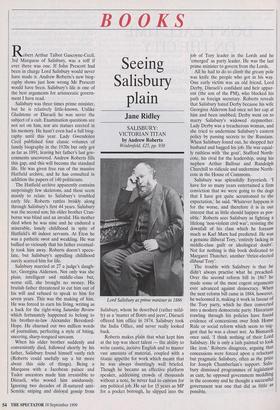

SALISBURY: VICTORIAN TITAN by Andrew Roberts Weidenfeld, f25, pp. 938 Lord Salisbury as prime minister in 1886 Salisbury, whom he described (rather mild- ly) as a 'master of flouts and jeers', Disraeli offered him office in 1874. Salisbury took the India Office, and never really looked back.

Roberts makes plain that what kept him at the top was sheer talent — the ability to write caustic, incisive English and to master vast amounts of material, coupled with a titanic appetite for work which meant that he was always dauntingly well briefed. Though he became an effective platform speaker, addressing crowds of thousands without a note, he never had to canvass for any political job. He sat for 15 years as MP for a pocket borough, he slipped into the job of Tory leader in the Lords and he `emerged' as party leader. He was the last prime minister to govern from the Lords.

All he had to do to climb the greasy pole was knife the people who got in his way. One early victim was an old friend, Lord Derby, Disraeli's confidant and heir appar- ent (the son of the PM), who blocked his path as foreign secretary. Roberts reveals that Salisbury hated Derby because his wife Georgina Alderson had once set her cap at him and been snubbed; Derby went on to marry Salisbury's widowed stepmother. Lady Derby was a treacherous woman, and she tried to undermine Salisbury's eastern policy by passing secrets to the Russians. When Salisbury found out, he shopped her husband and bagged his job. He was equal- ly ruthless with 'the goat', Stafford North- cote, his rival for the leadership, using his nephew Arthur Balfour and Randolph Churchill to ridicule and undermine North- cote in the House of Commons.

Salisbury was splendidly Eeyoriesh. have for so many years entertained a firm conviction that we were going to the dogs that I have got quite accustomed to the expectation,' he said. 'Whatever happens is for the worse, and therefore it is in our interest that as little should happen as pos- sible.' Roberts sees Salisbury as fighting a lifelong 'non-violent civil war', resisting the downfall of his class which he foresaw much as Karl Marx had predicted. He was a genuine illiberal Tory, 'entirely lacking in middle-class guilt or ideological doubt'. Not for nothing is this book dedicated to Margaret Thatcher, another 'thrice-elected illiberal Tory'.

The trouble with Salisbury is that he didn't always practise what he preached. Over the second reform bill in 1867 he made some of the most cogent arguments ever advanced against democracy. When the next reform bill came in 1884, however, he welcomed it, making it work in favour of the Tory party, which he then converted into a modern democratic party. Historians trawling through his policies have found evidence of concessions over Irish Home Rule or social reform which seem to sug- gest that he was a closet wet. As Bismarck once said, 'I think nothing of their Lord Salisbury. He is only a lath painted to look like iron.' Roberts disagrees, arguing that concessions were forced upon a reluctant but pragmatic Salisbury, often as the price for Joseph Chamberlain's support. Salis- bury dismissed programmes of legislation as cant, he opposed government meddling in the economy and he thought a successful government was one that did as little as possible. Roberts makes strong claims for Salis- bury's foreign policy. He argues that Salis- bury was not a splendid isolationist but a practitioner of non-alignment, intent on keeping Britain out of continental involve- ment and avoiding major wars. Had he been around in 1914, Roberts suggests, he might have kept the country out of the first world war, now increasingly seen as an avoidable catastrophe.

Of course, Salisbury was lucky. Glad- stone's Home Rule split the Liberal party, and Salisbury picked up the pieces. Though he despised the electorate, he won three landslide elections. As prime minister, he enjoyed an extraordinary personal ascen- dancy. Once he'd dumped the flamboyant, mercurial, chain-smoking Randolph Churchill, the Michael Portillo of the late- Victorian Tory party, he had no real rivals. His cabinets were cosy (they didn't meet on racing days, in deference to the Duke of Devonshire) and Salisbury told them very little. His ministers, who looked like over- weight walruses with whiskers sprouting from their high collars, were too polite to grumble. The real decisions were made by Salisbury and his right-hand man Arthur Balfour, whose house in Carlton Gardens was linked by private telephone to Salis- bury's in Arlington Street. Salisbury him- self controlled foreign policy by private correspondence, bypassing the Foreign Office and infuriating his officials. He was obsessively secretive and enviably self- reliant. 'Until my own mind is made up I find the intrusion of other men's thoughts merely worrying,' he once remarked.

Salisbury lived a blameless private life; there was nothing remotely sexy about him. He was endearingly eccentric, vague, untidily dressed and modest. It's hard to resist an 18-stone prime minister who took his daily exercise on a giant tricycle, wear- mg a purple velvet poncho. Yet when he retired in 1902 his system was in ruins. He bequeathed a divided, out-of-touch party top-heavy with his own relations (`the Hotel Cecil') to his successor Balfour. The Boer war, over which he presided, left Britain overstretched and isolated, fatally undermining his non-alignment policy. This book is over 900 pages long, which is good value for £25, though the detail, especially on the later governments, is sometimes wearisome and unfocused. His- torians won't like the footnotes, which are too skimpy for a document-based work of this importance. Roberts's approach is remorselessly chronological and political; even the influential Lady Salisbury is only a sketchy presence, and the Cecil family, who afford wonderfully rich copy, appear only as walk-on parts. But these are caveats. Roberts succeeds triumphantly in his pur- pose, which is to restore Salisbury to the centre of the political stage. Roberts makes IM secret of his sympathy for his subject, and he writes a readable, fluent narrative. This is an affectionate, admiring, detailed Portrait of a neglected giant.

Previous page

Previous page