Neighbourhood watch

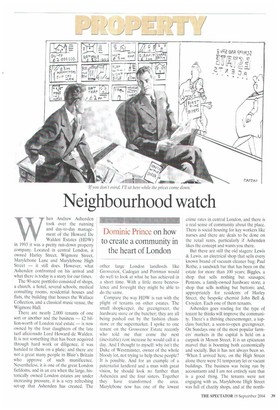

Dominic Prince on how to create a community in the heart of London

Iv hen Andrew Ashenden took over the running and day-to-day management of the Howard De Walden Estates (HDW) in 1993 it was a pretty run-down property company. Located in central London, it owned Harley Street, Wigmore Street, Marylebone Lane and Marylebone High Street — it still does. However, what Ashenden confronted on his arrival and what there is today is a story for our times.

The 90-acre portfolio consisted of shops, a church, a hotel, several schools, medical consulting rooms, residential houses and flats, the building that houses the Wallace Collection, and a classical music venue, the Wigmore Hall.

There are nearly 2.000 tenants of one sort or another and the business — £2 billion-worth of London real estate — is now owned by the four daughters of the late turf aficionado Lord Howard de Walden. It is not something that has been acquired through hard work or diligence, it was handed to them on a plate; and there are not a great many people in Blair's Britain who approve of such munificence. Nevertheless, it is one of the great London fiefdoms, and in an era when the large, historically owned London estates are under increasing pressure, it is a very refreshing set-up that Ashenden has created. The other large London landlords like Grosvenor, Cadogan and Portman would do well to look at what he has achieved in a short time. With a little more benevolence and foresight they might be able to do the same.

Compare the way HDW is run with the plight of tenants on other estates. The small shopkeeper, the greengrocer, the hardware store or the butcher; they are all being pushed out by the fashion chainstore or the supermarket. I spoke to one tenant on the Grosvenor Estate recently who told me that come the next (inevitable) rent increase he would call it a day. And I thought to myself: why isn't the Duke of Westminster, owner of the whole bloody lot, not trying to help these people? It is possible. And for an example of a paternalist landlord and a man with great vision, he should look no further than Ashenden and the four sisters. Together they have transformed the area. Marylebone now has one of the lowest crime rates in central London, and there is a real sense of community about the place. There is social housing for key workers like nurses and there are deals to be done on the retail rents, particularly if Ashenden likes the concept and wants you there.

But there are still the old stagers: Lewis & Lewis, an electrical shop that sells every known brand of vacuum cleaner bag; Paul Rothe, a sandwich bar that has been on the estate for more than 100 years; Biggles, a shop that sells nothing but sausages; Pentons, a family-owned hardware store; a shop that sells nothing but buttons; and, appropriately for residents of Harley Street, the bespoke chemist John Bell & Croyden. Each one of them tenants.

Ashenden goes touting for the type of tenant he thinks will improve the community. There's a thriving cheesemonger, a topclass butcher, a soon-to-open greengrocer. On Sundays one of the most popular farmers' markets in the capital is held on a carpark in Moxon Street. It is an epicurean marvel that is booming both economically and socially. But it has not always been so. 'When I arrived here, on the High Street alone there were 51 temporary let or vacant buildings. The business was being run by accountants and I am not entirely sure that is a good thing. The tenants were not engaging with us. Marylebone High Street was full of charity shops, and at the north em end we had a tyre-fitting garage, which I did not feel was conducive to community. Harley Street was under increasing pressure and was no longer a centre of excellence,' says Ashenden.

Take a stroll through Marylebone village with him and along the way you are stopped and hailed by individuals — all tenants — who greet him in a friendly and effusive manner. The local estate agent, cheesemonger, restaurateur, they all know him and seem genuinely to like him. So is he a 'good bloke', I wonder?

'What I have tried to do is think about the long term here. To help the tenants, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't but at least we have tried. When I hear that a tenant is moving, the first thing I ask them is "Why?" If there is a dispute with a tenant I want to know about it immediately and I want to know what we can do to resolve it, and how to avoid it happening again,' he says.

The tenants have a 24-hour hotline which they can ring should they have a leaking roof, a broken window or some other annoyance. This facility has not been without its problems, though. 'We did have a particularly troublesome tenant who once rang at 3 a.m. complaining that the rain falling on the glass roof was keeping him awake — he wanted to know what we were going to do about it,' says Ashenden incredulously.

At the top end of the High Street, where there was once the tyre fitter, there is now a Conran shop which has a restaurant and a food shop. It was one of the first shops Ashenden lured in, and other retailers soon followed.

'We had a site that was a natural for a supermarket. but I didn't want any old supermarket. Both Tesco and Sainsbury's offered more than Waitrose. But we went with Waitrose — and it has been a great success.' Ashenden asked the supermarket group to create a tiled mural of Marylebone, and the company donated a magnificent clock which now overhangs the High Street in splendid fashion. Waitrose Jives cheek by jowl with the smaller specialist food retailers — they all thrive.

And if they thrive, the estate does too. 'If we can attract small retailers who make a success of it and their takings increase, then of course our rental income goes up too,' says Ashenden.

The estate holds a summer fair in June with all shops donating funds to run the jamboree. This year the Royal Academy of Music (a tenant) and three local schools (also tenants) provided the entertainment while the retailers profited from the influx of hungry punters.

Ashenden is a man with an instinctive distrust of the fourth estate. I first met him two years ago after I had written something about HDW that he profoundly disagreed with. Rather than go to war I took him to lunch, we sorted out our differences and he explained his philosophy. It made a great deal of sense, and it still does.

'In the beginning I thought if we get the High Street into good shape, then everything else will follow. Harley Street was a different matter though. Here was the bestknown medical street in the world but it was in such a state of disarray that I actually thought it was terminal when I first arrived.'

But Harley Street has made a huge comeback also, the estate has invested funds installing high-tech medical facilities in low-tech period buildings and the result is that there are now more than 300 doctors and dentists back in tenure and it is once more on the up.

'There is a London borough that owns an entire high street, they're coming to see me shortly to see how they can revitalise it,' says Ashenden. But when I think could this be Lambeth or Hackney and ask him which of the many boroughs it is, he errs on the side of caution: 'No I won't tell you which one. It would be breaking a confidence.' A bit of me thinks he can see the headline already: 'Left-wing loonies ask toffs for help', perhaps.

But it shouldn't be just local authorities asking to see Ashenden; John Prescott should get to the head of the queue pronto, and we might then get a proper privatepublic partnership going.

Previous page

Previous page