DHOW -CHASIN G.* This is a very painful book, so

painful that one almost resents the occasional lightness of its tone, and has to remind oneself that what one reads currently was not so written, to escape the un- pleasant jarring of a jest or an amusing anecdote with the horrors of the " experience " of the Commander of the Castor and the Daphne. It is a book which every one ought to read, painful though it be, so that every one may understand what it is England will have ultimately to exact from the Sultan of Zanzibar, and why she must exact it, and afterwards make very sure that she continues to get it. It tells the horrid truth so plainly and so simply, that it is sure to inflame "the old fever" of anti-slavery, as the Bishop of Winchester calls it, which has broken out again, and if ever we fall into any such mistake as "putting a fine point upon" our treaties with the barbarous petty Sultans and puny potentates whom we have the power to coerce out of the atrocities of their slave-dealing, it will not be for want of an authentic record of the result of such absurdities of misapplied civilisation.

In 1868 and 1869, Captain Sulivan was, with other com- manders, fortunate enough to assist in liberating no less than 2,179 negroes, a number which gives a startling notion of the traffic in slaves as it now exists on the East Coast of Africa, and will enable the general reader to appreciate the urgency and import- ance of the efforts now being made by our Government to suppress it ; while the details of these feats of liberation will teach him how devilish are the cruelties England has to prevent or punish, and how vile is the " free-negro " pretext made by the Portuguese settlements, a pretext that has deceived many well-meaning persons. Captain Sulivan takes especial pains to expose and explain what he calls " the legal trader's slave trade," a very troublesome form of this wickedness, which frequently baffled him ; reducing him to the horrid necessity of leaving numbers of wretched creatures to their fate, even after he had ceased to be deceived. This is a brief extract from his account of the system,—

" By legal trader's slave trade' is meant that trade carried on in the coasting dhows which are engaged legally in conveying the produce of the country, and in illegally smuggling as many slaves as they can stow away with the least possible risk, but which have no licence or authority for conveying them even in Zanzibar waters, where it is possible to obtain such licences. The negoda (captain), whether he be owner or not, purchases a few slaves at the first port he puts into, and increases their number at each port as he proceeds north, until, as the dhow nears the destination it is finally bound for, she has become filled with slaves, stowed in all manners of ways, and unless the cargo is such as they can be fed from, they are in a starving condition."

What a horrid significance there is in that sentence, "stowed in all manners of ways!" What varieties and extremes of human suffering it suggests I In cases of this kind detection was very difficult in Captain Sulivan's time, but happily it is so no longer, owing to the employment of interpreters. He had no interpreter on board the Castor, and therefore could not question the negroes, who were made to pass for the crews of the dhows he boarded,

* Dhow-Chasing in Zanzibar Wafers and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. Narrative of Five Years' Experience in the Suppression of the Slave Trade. By Captain G. L. Sulivan, R.N. London: Sampson Low and Co.

and from subsequent experience, when he was well up in the tricks- ' of the slave trade, he is convinced " that hundreds of slaves must, have so run the gauntlet and passed them." These poor creatures at least had not to suffer the additional misery of beholding aid, and not daring to claim it ; they were not like shipwrecked men upon a raft, who see a ship approach and then sail away from them; their captors are too cunning for that.

"Ono morning wo had an exciting chase after a dhow, which there would have been no chance of overtaking but that the wind fell to a calm, which enabled us to use our oars, and on our going on board we found a numerous and grotesque crowd arranged about the vessel, to play various parts. There were about twenty or thirty negroes pre- tending to be very busy accomplishing wonders in unstowing or stowing some cargo, rolling up sails, hauling taut ropes that ought to be lot go, and letting go ropes that ought to be hauled taut ; they had no doubt been frightened into this vigorous and deceptive action by the usual Arab story that ' white man eat black man if he get him.' About twenty black men were dressed up in Arab costume, having a few negrosses by their sides, who never before were so rolled up in cotton, lashed up like hammocks, with nothing but their eyes appearing ; and half-a-dozen genuine Arab brutes, one of whom appeared to be monarch of all he surveyed. . . . . . The papers arc produced; they aro unintelligible to us. We could do nothing, wo had no proof that the dhow was a slaver, we had no conception of the trade being carried on in that way ; indeed, the efforts of the cruisers were principally directed against American and European vessels, which wore supposed to be carrying on the most extensive trade. We loft the vessel with the astonished Arabs in ecstacies of delight."

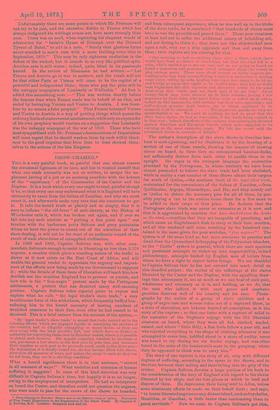

The author's description of the slave dhows in Zanzibar liar bour is most agonising, and he illustrates it by the drawing of a section of one of these vessels, showing the manner of stowing slaves on board, in three tiers on extemporised bamboo decks,.

not sufficiently distant from each other to enable them to sit upright. He urges in the strongest language the enormities practised by the Portuguese, in whose territory we have been almost persuaded to believe the slave trade had been abolished, while in reality a vast number of these dhows obtain their cargoes far south of Quiloa,—the southern limit of the legal slave trade, maintained for the convenience of the Sultan of Zanzibar,—from Quillimaine, Argoya, Mozambique, and Ibo, and they merely call at Quiloa to obtain the necessary pass for all of them, by pos- sibly paying a tax to the custom house there for a few more Lo- be added to their cargo at that place. He declares that the Portuguese slave trade was never so extensive as it is now, and that it is aggravated by cruelties that have shocked even the Arabs- on the coast,—cruelties that they are incapable of practising, and which cause an Englishman's flesh to creep at their bare mention, and all this rendered still more revolting by the falsehood con- tained in the name given the poor wretches, "free negroes"! The system is of the same kind as, but more atrocious in practice and. detail than the Queensland kidnapping of the Polynesian islanders, as the " Coolie" system in general, which there are such specious and persistent attempts to tinker up into respectability, indeed.

philanthropy, attempts backed by English men of letters from whom we have a right to expect better things. We are thankful to Captain Sulivan that he has not entered into much detail on. this dreadful subject; the recital of the sufferings of the slaves, liberated by the Castor and the Daphne, with the appalling draw- ings that accompany it, are as much as we can bear of such pain, wholesome and necessary as it is, and holding, as we do, that the man who inflicts it with such grave and emphatic precision deserves well of his country and his race. Photo- graphs by the author of a group of slava children and a. group of negro men and women taken out of a captured dhow, in a state of starvation, are hideous beyond all conception, as is the story of the capture ; so that one turns with a rapture of relief to the narrative of the Daphne's voyage with the 332 liberated creatures on board, where they were all fed, clothed, tended,. named, and where " little Billy, a fine little fellow a year old, and who rejected everything iu the shape of clothing whenever it was attempted to cover him, toddled about in a gate of nudity, never was heard to cry during his six weeks' voyage, and was often found in the arms of the boatswain's mate in the gangway, whose duty he appeared to think was to carry him."

The story of one capture is the story of all, only with different degrees of suffering, according to the space in the dhows, and to the time between their sailing and their falling into the grip of the cruiser. Captain Sulivan devotes a large portion of his book to the consideration of the duty of England with regard to the slaves liberated by her ships, and the best places at which to land and dispose of them. He deprecates their being sent to Aden, unless some missionary efforts be made on their behalf there ; and says, "to locate liberated negroes on any distant island, such as Seychelles, Mauritius, or Zanzibar, is little better than condemning them to penal servitude." Now we come to Captain Sulivan's pet idea, one in which we heartily sympathise. He wants to have a depot or depots on the mainland of their native continent for all liberated Africans ; he wants to create a colony for them in their own country, whence the operation of the opening up of the great continent, which has hitherto been drained of its population and made desert by the vile slave trade, may be effected by their means,.—working backward from the coast, after the blessings of freedom, industry, and primary education shall have fitted them for such work. He takes it for granted—writing before the un- favourable news had reached us—that the issue of Sir Bartle Frere's mission will be the total abolition of the slave trade ; he defines the conditions which must be made, and he then proceeds to detail his plan for the formation of a settlement, to embrace a coast-line of eighty-five miles in length, from Darra Salaam to the Jufijy river, under English rule. This territory he would, have purchased " at any cost " from the Sultan of Zanzibar. The details are too long for extract ; they look very nice on paper, and we cannot discern anything unreasonable in them. They deserve serious consideration and discussion, and those who may be dis- posed to dismiss the idea of an English colony in the healthy mountainous country in the interior of Africa, to which suck a coast settlement as Captain Sulivan proposes would open the way, as a vision like that of Dr. Mayo's " Kaloolah," would do well to consider the evidence which he deduces from the recent history of Abyssinia.

Previous page

Previous page