Exhibitions

Derain: the Late Work (Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, till 17 March)

Oddly revered

Giles Auty

Ihave seen a great deal of painting which does not appeal to me at all. Its exponents are stuck in the mud and will have a lot of trouble to get out of it. But if the war is ever over, there will still be room for a tremendous shove. Cubism is really very stupid and increasingly revolts me.' So said Derain, one of the founding Fauves, in 1917 when in his 37th year. The current exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (30 Pembroke Street) is of paint- ings and drawings Derain made during the 1920s and '30s. Before the first world war Derain had anticipated the rappel a l'ordre which took place among his contempor- aries, of whom Picasso was perhaps the most notable, after the conclusion of hosti- lities. I consider Derain's great painting from this era, 'Le samedi', which is one of the glories of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, to be his finest work. His often irritating eclecticism of the post-war years was preceded in this by a more homogeneous style, albeit one based on Gothic and Romanesque traditions.

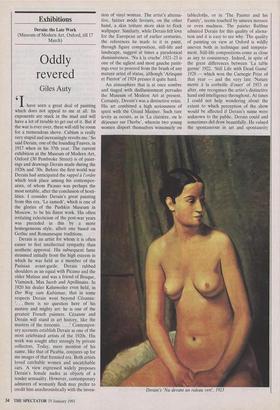

Derain is an artist for whom it is often easier to feel intellectual sympathy than aesthetic approval. His subsequent fame stemmed initially from the high esteem in which he was held as a member of the Parisian avant-garde. Derain rubbed shoulders as an equal with Picasso and the older Matisse and was a friend of Braque, Vlaminck, Max Jacob and Apollinaire. In 1920 his dealer Kahnweiler even held, in Der Weg zum Kubismus, that in some respects Derain went beyond Cezanne: `. . . there is no question here of his austere and mighty art: he is one of the greatest French painters. Cezanne and Derain will stand in art history, like the masters of the trecento. . . .' Contempor- ary accounts establish Derain as one of the most celebrated artists of the 1920s. His work was sought after strongly by private collectors. Today, mere mention of his name, like that of Picabia, conjures up for me images of that frenzied era. Both artists loved catchable women and uncatchable cars. A view expressed widely proposes Derain's female nudes as objects of a tender sensuality. However, contemporary admirers of womanly flesh may prefer to credit him anachronistically with the inven- tion of vinyl woman. The artist's alterna- tive, fuzzier mode favours, on the other hand, a skin texture more akin to flock wallpaper. Similarly, while Derain felt love for the European art of earlier centuries, the references he made to it in paint, through figure composition, still-life and landscape, suggest at times a paradoxical dismissiveness. 'Nu a la cruche' 1921-23 is one of the ugliest and most gauche paint- ings ever to proceed from the brush of any mature artist of status, although 'Arlequin et Pierrot' of 1924 presses it quite hard.

An atmosphere that is at once sombre and tinged with disillusionment pervades the Museum of Modern Art at present. Certainly, Derain's was a distinctive voice. His art combined a high seriousness of spirit with the Grand Manner. Such rare levity as occurs, as in 'La clairiere, ou le dejeuner sur l'herbe', wherein two young women disport themselves winsomely on tablecloths, or in 'The Painter and his Family', seems touched by unseen menace or even madness. The painter Balthus admired Derain for this quality of aliena- tion and it is easy to see why. The quality of painting on view at Oxford is wildly uneven both in technique and tempera- ment. Still-life compositions come as close as any to consistency. Indeed, in spite of the great differences between 'La table garnie' 1922, 'Still Life with Dead Game' 1928 — which won the Carnegie Prize of that year — and the very late 'Nature morte a la corbeille d'osier' of 1953 or after, one recognises the artist's distinctive hand and intelligence throughout. At times I could not help wondering about the extent to which perception of the show would be affected if Derain's name were unknown to the public. Derain could and sometimes did draw beautifully. He valued the spontaneous in art and spontaneity Derain's 'Nu devant un rideau vert', 1923 seems sometimes the sole redeeming fea- ture of his work, for many of his drawings are also extraordinarily inept.

Reputation in art is a strange business. I try, so far as possible, to forget name and fame altogether when confronted by works of art. The present Oxford show provides the rare and welcome chance to adopt just such a procedure with the art of Derain. The high degree of reverence he has enjoyed seems odd, if not incomprehensi- ble.

Previous page

Previous page