BOOKS

The hall of fame

Bevis Hillier

THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY by Charles Saumarez Smith NPG, £25, f17.50, pp 237 It is a sweet relief to be able to open a book on one of our national art collections and not find in it an illustration of, say, seven clothes-pegs fixed to a piece of corrugated iron and captioned 'Untitled Number Two'. Though I daresay that if Nicholas Serota of the Tate were translated to the National Portrait Gallery, before you could say 'conceptual art' there would be installed a gym-shoe balanced on a bidet entitled 'Lady Violet Bonham-Carter'. Or an inside-out plaster-cast of Betty Boothroyd by Rachel Whiteread, a bleaker Speaker.

Even the fanatical conspirators who keep the big business of modern art juggernaut- ing along accept that in portraiture some glimmer of a likeness is desirable and that the kind of mumbling in paint of a Rothko is not to be countenanced in countenances. Portraiture is the one realm of art in which the moderns can't get away with it. Of course — as their cheek is boundless and applauded — they have had a good try. In 1947 Patrick Heron wrote to T.S. Eliot ask- ing to be allowed to paint him. The letter contained the ominous sentence, 'I have for a long time been thinking around the problem of a portrait' — read: 'I have been wondering how I can profitably bugger up the dreary old tradition established by Hol- bein, Hogarth, Reynolds and Augustus John.' As Eliot had done much the same for English poetry, he could hardly refuse. The result, illustrated in this book, was a cubistic portrait for which this merit is claimed: 'Eliot is seen simultaneously both full face and in profile.' That is just the way Van Dyck portrayed Charles I; but, unlike Heron, he did not make the elementary mistake of superimposing the profile on the full-face — just the sort of double exposure that used to ruin my Brownie box-camera portraits.

The composition of Heron's painting is quite agreeable, in its arid genre, though it does not come close to the inspired pattern-making of Wyndham Lewis's portrait of Eliot, which the NPG does not possess. If you wanted to know what Eliot looked like, you could see his youthful self in two group photographs of the Harvard Advocate editors, owned by the Cincinnati Historical Society (they have been reproduced in none of the books on Eliot, nor anywhere else to my knowledge). Sir Gerald Kelly of Burmese Girl fame gave a good account of the middle-aged Eliot. And on 14 November 1956 Punch published Ronald Searle's magnificent double-page portrait of the poet in old age, with hardly a trace of caricature.

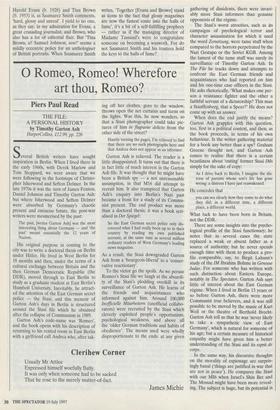

The nearest to abstraction that the English portrait has orbited is Ben Nichol- son's 1933 painting of himself and his future wife Barbara Hepworth — two fishily goggling and almost indistinguish- able profiles, approvingly described in the book as 'slightly prehistoric'. Sort of, What the Dino Saur. Apart from this picture and Coventry Patmore by John Singer Sargent, 1894 Heron's 'Eliot', none of the works illustrat- ed in Charles Saumarez Smith's largely skilful anthology from the gallery he directs needs strenuous decoding; and most of them are masterpieces.

The humble, self-effacing line about British art used to be: with our misty climate and watery skies, we excel in water- colour (Cotman, De Wint, Girtin, Charles Knight) but have not scaled the heights in oils. Ruskin recognised the quality of Turner; and in the 20th century Turner has been hailed as the first, and surely the greatest, of the Impressionists. But the tradition of British portraiture, informed by our delight in the individual and in individ- ual quiddity (the national trait which in Edmund Burke's view, saved us from the straitjacket of a written constitution), is perhaps our most significant contribution to world art.

Near the beginning of the tradition is the formidable figure of Holbein, represented here by a miniature of Thomas Cromwell's merciless face against a lapis lazuli back- ground. In one of his television master- classes, the cellist Paul Tortelier was asked the cliché question, 'Who is your favourite composer?' He replied: 'Bach — and any- one who gives you a different answer is not a musician.' Holbein is to art what Bach is to music: cerebral, rigorous, ruthlessly defined, heading for mathematical perfec- tion. But even those of us who venerate Bach might jib at Tortelier's dogma, comparable to F.R. Leavis's literary exclu- sionism in The Great Tradition. We might seek the freedom to press the claims of Mozart or Beethoven. Saumarez Smith parades before us the artistic equivalents. Gainsborough, whose self-portrait is illus- trated, is the Mozart of English art serene, humane, humorous, rococo. (Admittedly, there is no Gainsborough Requiem.) Sir Thomas Lawrence and Benjamin Robert Haydon are Beethovens — heroic, bravura rule-breakers. Strategi- cally blown-up details, as well as the portraits themselves, bring home to us how masterly are Lawrence's 'William Wilber- force' (another heroic rule-breaker) and Haydon's 'William Wordsworth'.

In making his selection, Saumarez Smith has had to strike a nice balance between eminent sitters and eminent artists. The NPG is, after all, our national pantheon. It would be unthinkable not to include Shakespeare, even though the painting, which shows the dramatist with a gold ring through one ear like a modern bus- conductor, is an indifferent work attributed to the actor-painter John Taylor. (It certainly resembles the Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio of 1623.) An odd omission is Dr Johnson, a figure who could belong to no other nation. His head by James Barry was very properly chosen, with a portrait of Elizabeth I, to go on the jacket of K.K. Yung's Complete Illustrated Catalogue of the NPG in 1981.

Among the artists, the revelation, to me, is John Everett Millais. I had pictured him as one of the prissier members of the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood and had thought of the Brotherhood as obsessed with a petit-point, fiddle-faddle technique — every blade of grass, and all that. But the detail of Disraeli's head shows that Millais was capable of the grand sweep, too. The inky shadow under the sarcophagus-lid eye- hoods is slashed in with two scything strokes of a loaded brush, as negligent and unerring as a Chinese calligrapher's. Saumarez Smith records:

In 1881 Millais wrote to Disraeli pleading, 'I know that sitting to an Artist is attended with great inconvenience to Every public man, but I do hope you will allow me to make a portrait of your Lordship.' Disraeli replied: 'I am a very bad sitter, but will not easily forego my chance of being known to posterity by your illustrious pencil.' At the time of Disraeli's death, the portrait was unfinished and was completed at Queen Victoria's request . . .

As Saumarez Smith writes, Millais's `Disraeli' dignifies the sitter. One wants to see casual, off-duty images of the great, as well as official portraits. The cartoonist Harry Furniss described how Disraeli's secretary, Monty Cony, trotted the ageing statesman out for a walk so that Carlo Pellegrini (`Ape' of Vanity Fair) could surreptitiously sketch him. Furniss drew a caricature of the dandified 'Ape' sketching Dizzy — the biter bit. The gallery has over 1,000 drawings by Furniss, and held a fine exhibition of them in 1983, but unfortu- nately the Dizzy/ 'Ape' one is not among them.

Another portraitist I used to misjudge along with Millais is John Singer Sargent, best known as a 'society painter' of rich Edwardian beauties — well, beauties after he had done with them, anyway. I had too easily accepted the art historians' view that he was 'superficial' — only his fellow society painter Philip De Laszlo being more despised. (Roger Fry thought Sargent `undistinguished as an illustrator and non- existent as an artist'.) My conversion to Sargent began in the late 1960s when Richard Ormond, then Roy Strong's deputy at the NPG and now head of the National Maritime Museum, showed me dazzling sketches by Sargent, a kinsman of his. And now the reproduction, in this book, of Sargent's portrait of the poet Coventry Patmore, with another of those blown-up details of the head, convinces me that Sargent was a master. His technique of jabbing, dabbing, dartingbrushstrokes, so often described as 'flashy', was clearly bor- rowed from Frans Hals, a sort of pointil- lisme with chunky points. As with Hals, this apparently insouciant brushwork brings out profound underlying character — rather as scattering breadcrumbs on a lake brings big fish to the surface. I think Eleanor Ruggles must have had a good look at Sargent's portrait when she wrote of Patmore, in her 1947 biography of Gerard Manley Hopkins:

He was tall, his frame cadaverous; his head was small and finely shaped — its set was arrogant. His eyes, too, were small and bright with humour with their heavy lids; while his splendid grey curls, brushed back from his forehead and of a length to fall just below his ears, resembled those of an actor, an American cotton planter, or a vendor of patent medicines.

Looking at the portrait, I remember how Patmore's poem 'The Angel in the House' got up Virginia Woolf s nose (always a per- ilous ascent), with its assumption that women were there to minister to men. But Ruggles was right about the humour in the eyes. There is something in this face that prompts flippancy and facetiousness. Even the learned John Sparrow, Warden of All Souls, was moved to write a poem of matchless silliness about Coventry Patmore — 'To an Angel in the House', published in Grave Epigrams and Other Verse (1981):

A pat on the head Sends me happy to bed, I wish — how I wish — you'd do that more!

Cold words and neglect Leave me wretched and wrecked: Don't send me to Coventry — pat more!

One clear lesson from this anthology is that a good likeness is not necessarily a good painting; and vice-versa. Sir James Gunn's 1950 portrait of Clement Attlee is an excellent likeness: we know that from photographs and films of the statesman. But it is a thing of dead textures, devoid of inspiration. (When I hear the word Gunn I reach for my culture. Or: when I hear the word Gunn, I reech, period.) If it were not so lifeless, one might say that the Attlee picture is the living disproof of Gunn's complacent dictum, 'An artist does not need to be a judge of character if he paints what he sees and paints it sincerely.' By contrast, in Ruskin Spear's impressionistic 1974 portrait of Harold Wilson materialis- ing from a cloud of tobacco smoke like a genie, the former prime minister looks just on the point of delivering a put-down to David Dimbleby in that crunchy William Hague voice of his.

With sitters who were photographed, we can tell if a painted likeness is good; but how do we know in the case of somebody born before the camera was invented? When a figure has been often portrayed, you build up a kind of pictorial consensus. The portrait of Alexander Pope selected for this book is a telling profile by Jonathan Richardson. Pope is shown about 1737, seven years before his death; the head under the Laureate's crown of leaves is ravaged by illness. Saumarez Smith makes the point that Pope sat to almost all the major artists active in his lifetime; and David Piper, a previous director of the NPG, astutely guessed that

Vanity was intensified by the need to rectify the tragic, twisted reality of his crippled body with an image worthy of the lucid, beautifully articulated construction and spirit of his portrait.

Lord Rees-Mogg, who amassed a large hoard of images of the poet, once described as 'a very catholic collection of Popes', would be able to say whether the Richardson painting is a good likeness. I do not doubt that it is, because Pope appears even more gaunt and hollow-cheeked in a superb marble bust of 1741 by Louis- Francois Roubiliac, recently sold by Sothe- by's. (By one of those pleasing coincidences which sometimes occur in life as well as novels, the same auction contained Roubil- iac's equally sublime bust of the collector Sir Andrew Fountaine, whom Pope had derided in The Dunciad:

But Annius, crafty Seer, with ebon wand, And well-dissembled em'rald on his hand, False as his Gems, and cancer'd as his Coins, Came, cramm'd with capon, from where Pollio dines.)

Almost all critics now accept that photographs can be art; and some of the finest images in the book are photographic. The NPG postcard that sells best, we are told, is a 1902 photograph of Virginia Woolf. The 1857 photograph of the engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, tall- hatted and cigar-chomping in front of a steamship's massive launching chains, convinces far more than Kneller's attitudin- ising portrait of Sir Christopher Wren in 1711. By a quirk of fate, Gerard Manley Hopkins had an uncle, Judge George Gibeme, who took photographs of him as a boy in 1849. (The judge's grandson, the BBC broadcaster Lance Sieveking, wrote about this in his memoirs.) Sadly, the NPG has none of these plates.

Today the gallery buys and commissions portraits of living celebrities. It is a contro- versial policy. I mean, not everyone in Who's Who gets into the Dictionary of National Biography; perhaps death and a decent interval should precede admission to our pantheon. The artists are not always the happiest choice, either. In this book there is no work by any of our four best living portrait painters — Lucian Freud, Derek Hill, David Hockney and James Reeve. Instead we have the ubiquitous Maggi Hambling, who manages to make Stephen Fry (b. 1957) look like the Elephant Man. (The caption notes that the work 'was acquired by the Trustees on the afternoon of the day that Fry disappeared from public view, halfway through the run of . . . Simon Gray's play Cell Mates'.) And a rebarbative picture of Germaine Greer (b. 1939) by Paula Rego, which gives her the appearance of a man recovering from a gruelling sex-change operation. And a most uncharacteristic photograph of Margaret Thatcher (b. 1925) by Helmut Newton, better known for his erotic shots of young girls.

David Buckland's Cibachrome print of Harold Evans (b. 1928) and Tina Brown (b. 1953) is, as Saumarez Smith comments, `hard, glossy and unreal'. I yield to no one, as they say, in my admiration for Evans, a great crusading journalist, and Brown, who also has a lot of editorial flair. But 'Tina Brown, si! Samuel Johnson, non!' seems a mildly eccentric policy for an anthologiser of British portraits. When Saumarez Smith writes, 'Together [Evans and Brown] stand as icons to the fact that glossy magazines are now the fastest route into the halls of fame', it's a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy — rather as if the managing director of Madame Tussaud's were to congratulate someone on becoming a waxwork. For do not Saumarez Smith and his trustees hold the keys to the halls of fame?

Previous page

Previous page