PRICE OF COALS.

ENGLISHMEN boast of the snugness and homefelt character of their enjoyments, as more than sufficient compensation for the gaudy and superficial pleasures of other nations. Even our cold and weeping climate appears tons to be cheaply exchanged against what no nation but our own and those which draw their customs from its example possess—our cheerful and lightsome hearths. Now, the first requisite for this national pleasure is, we believe by universal admission, coals. Yet, strange as it may appear, we, who sum up our expression of domestic delight by the single phrase "an Englishman's fireside," have hitherto been wonder- fully reckless touching that material without which a fireside is not only a cold but a comfortless affair into the bargain. Some years ago the kingdom was up in arms about the salt-tax. lithe whole population from Cornwall to Caithness had been on the eve of setting out on a voyage round the world, and every house- wife called on to pickle a couple of years' provisions, there could not have been a greater racket. This year a cry has gone along the land for cheap beer. But what, after all, are pickle and porter, either separately or conjointly, compared with a roaring, blazing fire ?—the companion of solitude, the solace of company, the zest of the wealthy, the all in all of the poor ! Yet this very fire, to which even in the midst of June we are at present compelled to have recourse, as without its assistance our genial pages must have been cold and cloudy like the sky that lights us, is as scan- dalously taxed as either salt or beer have been. And the tax is not only scandalous in amount, but partial in its operation, inde- nde fensible fensible in its principle, and accompanied, as all ill-judged taxes are, by regulations that make it still more indefensible in practice.

Many good folks, when they are4old that the tax on coals is six shillings the chaldron, and who find by sorrowful experience that a chaldron costs them occasionally three . pounds, may think lightly of the addition that Government makes to the already enormous price. But they will change their opinions when they lead' that this said six shillings makes in reality fifty per cent. of the prime cost of the article ; and that through every hand that it passes before it reach the consumer,. the profits justly added to the price are enhanced by one-half in consequence of the first imposition.

And this is not all. Suppose. that every chaldron of coals that reached the pit's mouth should pay fifty per cent. It would be bad enough that snch a tax should be levied on the piimest necessary of life—on an article which is essential to our manufactures in every stage of their progress : still, if it were laid equally on all, its justice could not be blamed, whatever were said of its expediency. But the Government coal-duty is far more hateful than this. When the PERCY in his hall burns his coals undisturbed by the tax-gatherer, the pauper of Westminster in his garret cannot warm his chilled blood without giving up to Mr. GOULBURN a portion of the parish allowance for the indulgence. Again, if you drag your coals along a railway, or convey them by a canal, you may blow the bellows in peace ; but if you commit the carriage of them to the winds and the waves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer will have one side of the chimney, let who will take the other. The poet tells us that Jupiter interposed the ocean between the various empires of the world in order to keep people and produce from gadding abroad. The regulations of our Government come in kindly and considerate supplement of those of Nature.

" Divisum imperium cum Jove Cmsar habet."

The terrors of the sea were insufficient to keep Newcastle coals at home, and so we added the more substantial terrors of the Cus- tomhouse.

The thing is hideous in principle. We can sympathize with those who call for the imposition of taxes on articles of foreign production. It requires a familiarity with the higher economics to perceive that heavy duties of every kind are injurious to those who lay them on. But among the sturdiest sticklers against free trade, there can be but one opinion respecting the absurdity of taxes which go to in- terrupt the communication between different provinces of the same kingdom. What would be said of a law which should forbid the importation of hops or, potatoes from Kent into Middlesex unless on payment of fifty per cent? And yet, how would such a law differ from that which imposes fifty per cent. on coals imported from Northumberland or Durham into Middlesex ?

But then comes . the grand argument, the ultima ratio of cabinets —" The tax is heavy,-it is padiai, It Is -unprineipled ; but we get eight hundred thousand pounds a-year from it, and we cannot give up so large a sum." If you cannot give up so large a sum, say we to such reasoner% then seek it elsewhere. To persist in an ad- mitted bad tax from any pretended or real difficulty in finding a suitable one for which to exchange it, is to declare yourselves igno- rant of the principles of honest government, or unwilling to follow them.

There is an evil adhering to the coal-tax that we have not yet enumerated. The Chancellor of the Exchequer is very jealous of his manor—he can on no account admit of poachers there ; and in his zeal to check their nefarious attempts, he generally contrives very materially to enhance the burdens he lays on the honest. But in the case of coals, he has aggravated the burdens of the public in another way—by his regulations to prevent, not himself, but them, from being cheated. Having contrived to pick poor John Bull's pocket of almost a million per annum by his tax on coals, he is most tenderly anxious that John should be protected, as much as possible, from other robbers engaged in that dark traffic. We do not altogether object to this sort of Rob Roy honesty—this system of protection from petty plunderers, that the greatest . plunderer of all may levy his black mail in the greater security ; but we decidedly object to the means by which it is sought to be obtained. It is not generally known, that the more you break coals; the mote they give out in the measure. Dr. HurroN states the proportion between coal in bulk and when broken into good-sized pieces, to be as 5 to 7i ; and where the pieces are very small, as 5 to 9—that is, a mass of coal which measures five bushels, when broken moderately, will measure seven and a half; and if broken very small, will measure nine bushels. Can any thing more ridiculous be imagined, than, under such circumstances, to make measure the standard by which coals must be sold ; and to get up a whole bushel of laws, for the purpose of rendering such a protection to the public complete, which, when complete, is no protection at all? The plain remedy for this evil is to make weight the standard.

Thus far we have treated the coal question in general terms ; we shall now proceed to apply to it a more particular test. The following tables have already appeared in a pamphlet,* improved and enlarged from a useful article in the Edinburgh Review, which we strongly recommend to the notice of every one who can obtain a perusal of it. We have printed in italics those items Which are either altogether unnecessary, or greatly overcharged.

* Remarks on the Coal 'Trade, and on the various Duties and Charges on Coal In the Port of London, 8m. Reprinted, with Additions and Corrections, from the Edinburgh Review, No. 101.

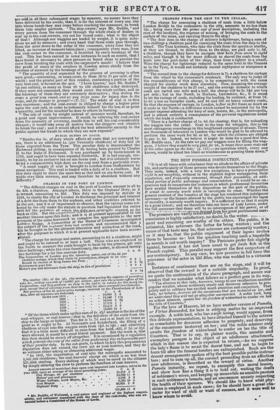

-Charge of Sale and Delivery into Barges in the Port of London, including Municipal Dues.

The Corporation of London for Metage . . . 0 0 4

Ditto for Orphan's Dues . . . . . . 0 0 10 Market-dues to defray the purchase of the Coal-Ex- change, and expense of that establishment . 0 0 1

Meter's pay, and allowance 0 0 4

Factor's commission 0 0 4 Trinity dues and Stamp 0 0 4 Water baillage, and Lord Mayor for permit, charges of meters' office, &c. . 0 0 0} Scorage and Ingrain, customary allowance to the

buyers, variable, but may be stated to average 0 2 6 Coal whipper, delivering from the ship into the barges 0 1 7

0 6 41

Deduct whipping, Is. 7d. and ship metage, 4d., paid tout of the freight 0 1 11

0

Coal Merchant's charges from the ships, 1 in the Pool, to the consumer's Cellar.

Lighterage from the ship to the wharf . . • 0 2 0

Cartage, including the loading of the waggons . 0 7 0

Unloading from waggon to cellar, called shooting 0 I 6 Land Metage . . ... • 0 4 0 Commission to buyer

- 0 12

STATEMENT OF THE EXPENSES ON THE TRANSIT OF COALS FROM THE COAL-OWNER TO THE CONSUMER.

On the Wear, the Price paid to the Coal-owners s. d. I. s. d.

For Stewart's Wallsend 0 14 0 For Eden Main 0 12 0 0 13 0 0 0 3 0 0 3} 0 0 6* Net price received by the coal-owner . . . . 0 12 Fittage and Keel-dues, when loaded by Tubs, distance Seven down the River, and other Charges in Sunderland Harbour.

Fittage and Keel-dues 0 2 3 Trimming in the ship . . • . 0 0 22 Coast Lights, &c. . . . 0 0 5 Pilotage and assistance to sea . . 0 0 2} Average . . . Deduct duty paid by the Coal-owner to the Commissioners of the river Wear, by Act of Parliament for improving; the Harbour, &c. . . . . . Cost of working the machine for tran- shipping the coals from the keels to the ships, paid by the coal-owners . .

Paid out of the freight . 0 0 10.1 0 Ship-Owners.

Freight from Sunderland to London 0 11 0

Government Duty 0 6 0 Expense of transit from coal-owner to consumer . 1 15 81,

When the coals are shipped in keels, in bulk without tubs, the fitter's charge is . . . . . 0 3 3 The charge, by tubs, including the expense Of work- ing the transferring engine, is . . . . 0 2 6} Extra cost to the coal-owner, when shipped by

keels in bulk . . . . . . 0 0 81

On the Tyne.

Russell's Wallsend are charged, put on board the ship at the spout, per London chalclron ... .. . The ft-eight ought, to pay the ship-owner fairly, to be . . Government-duty, including the Richmond shilling . . Factor's and port charges, municipal dues, &c., in London . Buyer's charges for landing and delivering into cellars . . 0 15 9

O 11 0 0 6 6

O 4 51 0 12 0 The coal-owner receives 2 9 81

O 15 9 .

Expense of transit from coal-owner to consumer 113 114 But take a Second-rate Coal, as Dean's Primrose, and the statement will stand as follows.

Coal-owner's price on board 0 11 0 Freight 0 11 0 Government-duties 0 6 6

Factors, &c •e 0 4 5* ' Buyers 012 0

:The coal-owner receives

2 4 11} 0 II 0

• . 1 13 11} Expense of transit from coal-owner to cellar .

On a;Second-rate Coal shipped from the most distant Collieries on a ' • Tyne, by Heels, the account stands thus.

Price charged by coal-owner . . . . . . 0 11 0

Deduct the proportion of the keel-dues paid by him • . G 1 . 6 Carry forward, 0 12 6

Total charges to consumer, supposing him to get the correct measure, and the sort of coal he orders 2 8 2

Net price received by the coal-owner • 0 12 51

Brought forward, L.0 12 6 Net price received by the coal. owner . . . . . 0 9 6 Then the charges are, keel-dues paid by the coal-owner . . 0 1 6 Freight 0

11 0 King's duties 0

6 6 Factor's, &c 0 4 51 Buyers, 8cc 0 12 0 Cost to consumer 2

17 51 The coal-owner receives 0 9 6 Cost of transit from coal-owner to cellar . 2 7 11}

Thus is the original price of coal QUADRUPLED in its transit from the producers to the consumers. This state of things, in the enlightened nation of Great Britain, must not outlive the year 1831! The Government-duty, of course, ought to be removed alto- gether. Of the City-dues, 4d. is for " metage," which ought to be wholly struck off; and 10d. is a tax originally for an orphan fund, but now continued for completing the approaches to London Bridge. Why should not the people of London pay for their bridge, as the people of Westminster have done for theirs ? What right or reason is there in laying a tax on the whole metropolis for the convenience of a part of it? And, if there were, can any thing be more infamous than to select from all others a tax which 2 3 presses so heavily on the poorest of the community? The same rule that applies to metage applies to meters' allowances ; and the " whippage " is even more objectionable. Why should not the crew of a collier unload their own vessel in the port of London, as they actually do in every other port in England? The "lighter- age" is unquestionably too high by one-half,* as well as the "cartage ;" and for the "shooting," as it is called, one-sixth part of the present charge would be amply sufficient. We have stated that weighing is in reality the only true method by which the public can be protected against fraud—fraud of the worst sort, which cannot be punished even when detected. Now, by the very simple expedient of a steelyard at the wharf, the weighing of a waggon could be gone about more easily than the measdring of a bushel. There is not the slightest reason for an additional charge for weigh- ing. Does a draper charge for measuring his cloth ? But if some charge were made, assuredly it would not amount to the present extravagant one of 14d. per chaldron. It would not, therefore, be going too far to state the saving which would directly accrue to the public from the removal of the coal-tax, and the removal of the absurd regulations by which it is accompanied, at 16s. or lie, per 4 5} chaldron ; and if to this'were added the abatements of price which the absence of useless and irritating restrictions would not fail to produce, the amount would not fail short of 208.; that is, the inhabitants of the metropolis alone would save 1,500,000/. per annum by the repeal of enactments on which every principle of political economy and of common sense cries shame. This is a sum worth looking after. 0 The inhabitants of London suffer most : but all the Southern Counties of England, as Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Middlesex, Kent, Surry, Sussex, Hampshire, and Devonshire, are obliged to import supplies of coal; and every place in England that receives its fuel by sea carriage is as much interested in the removal of the tax, with all the restrietions which enhance price, as the inhabit- ants of the metropolis can be. . Throughout this reckoning up of public wrongs, we have ab- stained from noticing the grievous injustice inflicted on the pro- prietors of coal-mines in the North. This is another branch of the question, which we may hereafter cliscuss,—in connexion with the undue advantage which the producers. of inland coals possess, in exemption from tax, and the monopoly of markets from which the owners of sea-borne coals are shut out. The manufacturers of those districts should attend to this view of the subject. In the mean time, let us be assured that the inhabitants of London, and of the whole Southern counties, have a common interest with the Northern coal-owners in seeking redress of these their common grievances. The profits of the coal-owners are brought to the lowest remunerating level by competition among themselves ; every penny of reduction in the tax and imposts must therefore go to the consumer. The coal-owner's share of the general ad- vantage consists in the extension of his markets and the increase of demand for his commodity.

FURTHER STATEMENTS OF FACT FROM THE PAMPHLET. ABUSES OF THE SYSTEM OF MEASURING.

"The smallness of the coal used in London is uniformly remarked by every individual from the North who visits the metropolis. And yet, sin • gular as it may seem, none but large coals are shipped from the Tyne and the Wear for London. The cause of the metamorphosis which the coal undergoes in its passage to the consumer, is not, however, difficult to.dis- cover ; and it strikingly illustrates the nature of the regulations under which the trade is placed. Coals are nominally sold by the owners to the shippers by weight, or by the chaldron waggon, which is supposed to con- tain, when full, 53 cwt., and is stamped as such by the officer of the Cus- toms. But the weight of the waggon depends in a great degree on the size of the pieces with which it is filled, so that in point of fact coal is sold by measure. It is stated by the celebrated Dr. Hutton that, If one coal, measuring exactly a cubic yard (nearly equal to Jive bolls), be broken into pieeeS of a moderate size, it will measure seven bolls and a half; if broken very small, it will measure nine boils; which shows that the proportion of the weight to the measure depends upon the size of the coals; therefore accounting by weight is the most rational method.' The shippers are well aware of this, and insist upon the coal-owners supplying them with large coal only; and to such an extent is this principle carried, that all coal for the London market is screened, as it is technically termed, or passed over gratings which separate the smaller pieces. Inasmuch, however, as coals • This charge is the result of a monopoly in the lighter trade, effected by means of the Incorporation of the Watermen's Company.

are sold in all their .subsequent stages by measure, no sooner have they been delivered by the owner, than it is for the interest of every one else into whose hands they may come before reaching the consumer, to break them into smaller portions. 'The ship-owner,' says Mr, Buddle, ' and every person from the consumer through the whole chain of dealers in coal up to the coal-owners, cry out for round coals; what is the object of that ? Although our waggons are loaded by weight, it is quite noto- rious we sell by measure; and every hand that those coals pass through, from the mine down to the cellar of the consumer, every time they are lifted, an increase of measure takes place; consequently every man, from the coal-owner to the consumer, is benefited by every breakage of the coal. This has been carried in some instances to such an extent, that I have found it necessary to place persons on board ships to prevent the crew from breaking the coals with the carpenter's mauls! I believe that the profit of many of the retailers in London arises chiefly from the increase of measure by the breakage of the coal.'

"The quantity of coal separated by the process of screening is often very great,—amounting, in some.cases, to from 20 to 25 per cent, of the whole; and the greater part of this residue, containing a portion of the very best coal, is burned on the spot. 'I have known,' says Mr. Buddle,* 'at one colliery, as many as from 90 to 100 chaldrons a-day destroyed. If they were not consumed, they would cover the whole surface, and in the burnings of them they are extremely destructive ; they destroy the crops a great way round, and we pay large sums for injury done to the crops, and for damage to ground!—(P. 72). The waste of coal is in this way enormous; and the coal-owner is obliged to charge a higher price upon the coal sold, in order to indemnify himself for the loss of so great a quantity, and for the mischief he does to others in burning. The sale of coals by weight instead of measure would, therefore, be a great and signal improvement. It would, by relieving the coal-owner

from the necessity-of screening, enable him to sell his coal considerably cheaper ; it would take away all motive from the shippers and retailers to break the coal ; and it would afford the best attainable security to the public against the frauds to which they are now exposed."

PUBLIC DUTIES ON COALS.

"Besides the 6.7. of duty which affects all coals that are conveyed by sea, there is an additional Is. (per Newcastle chaldron) of duty laid on those exported from the Tyne. This peculiar duty is denominated the Richmond shilling, in consequence of its having been granted by Charles IL to the Duke of Richmond. It was purchased up by Government in 1799, and ought to have been repealed forthwith. It is bad enough, cer- tainly, to lay an exclusive tax on sea-borne coal ; but it is infinitely worse to lay a comparatively high duty on the coal sent from a particular river. "A small supply of coal is brought to London from Staffordshire by Canal navigation. This coal is loaded with a duty of Is. a chaldron. But this duty ought to share the same fate as that laid on sea-borne coal. It yields very little revenue, and may therefore be abolished without any difficulty.'

CHARGES IN THE PORT OF LONDON.

"The different charges on coal in the port of London amount in all to 6s. 4dá. a chaldron. Amongst others, there is the Orphans' Duty, as it is termed, amounting to 10d. This duty was imposed by statute in 1694, to enable the city of London to discharge the principal and interest

of a debt due from them to the orphans, and other creditors referred to in the act; and it is of importance to observe, that the various sums col- lected by the city under the statute in question had liquidated the entire debt tot the pay men t or which ths„(N.Vl% er vl lv eranted so far back as 1782. But the eui put at.sua another thrown upon this duty ; and it is at present appropriated' to toe payment of the sums borrowed to complete the approaches to the new L01100*, Bridn. A Committee of the House of Commons investigated the subject or toe uipbans' duty last session, and recommended that a bill be brought in for the ultimate liberation and extinction of the fund, after the purposes to which it is at present applicable have been accom- plished. "The charge for metage and meter, amounting to 8d. a chaldron, might and ought to be reduced to at least a half. Those who are employed in the North to measure the coals brought ght to bank by the pitmen, get only three farthings ; while the civic functionary, the meter, s allowed twenty- two farthings for a far less onerous duty. 1. a. d. The Corporation of London pay the labouring meter, out of the 4d. per chaldron inetage, which they claim by prescription, alleged to be con-

0 0 I firmed by charter of King James the First 0 0 01 Government pays him

Meter's pay and allowance from the ship, in lieu of provisions 0 0 4 • 0 0 54 vats, Scc., netting upuards of 18,0001. per annum, goes into the prioate coffers of the post, except that of selecting from their own body the above overpaid functionaries. Corporation; and they perform no duty to the public in return for this heavy im- don, after all expenses are deducted.

coal-whipper, or coal-heaver—that is, the deliverer of the coals from the ship to the barge or lighter. This fee is is. 7d. and is at least six times as that it is a little more difficult to raise from the hold, still, if 3d. or 314. were allowed, it would be a most liberal payment. But the truth is, that great as it ought to be. At Newcastle and Sunderland, the filling of a chaldron of coal into the waggon costs from ad. to led. ; and admitting this item should be struck off altogether. It is occasioned by a regulation which prevents the crew of the collier from performing this indispensable part of their peculiar duty. In the out-ports, to which luckily this preposterous regulation does not extend, the crew act as coal-heavers, and they do so without either asking or obtaining additional wages.

by simply allowing the crew to perform the function of coal-heavers.

year 1828, upon an average of the three preceding years. l 8. d. 121,9801. sterling. Every shilling of which may he saved to the citizens 1,541,000 chaldrons; the coal-heavers' charge on which is no less than The residue (341.) of the 4d., city metage, after paying the expense of providing Net produce of the 4d. prescriptive metage, received by the Chamberlain of Lon- "Of the items which make up this sum of 68. 4y. another is the fee of the "In 1828, the importation of coal into the metropolis amounted to Annual amount of municipal dues upon coal imported into London, taken in the Water haillage, Lord Mayor, &c. . . . 3,229 3 3

City Metage, 9d. per chaldron . . . . 25,210 2 0 Meters' pay and allowances 24,068 11 0

Coal Market . ..... . 6,302 10 6 Orphans' Duty . . . • • • • 63,025 5 0

In the year 1824 1825 1826 1827 1828 . . . 18,632 14 5

19'083 82 19 340 7 111 18 645 6 9i 18 479 8 8 173"9 I 1

121,835 11 9

• Air. Huddle, of Wallsend, a coal-owner and engineer of the highest respect- ability, and intimately acquainted with the state of the coal-trade, who was es. mined before a Committee of the House of Lords.

Previous page

Previous page