The British Radical in 1959

Romantic Imperialist

By HENRY F A IRLIE

ORD BOOTHBY claimed recently that he was a radical, and that a radical such as he could exist only inside the Conservative Party. Without necessarily associating myself with all'his obstrep- erous views, I would make much the same claim. Certainly, I do not understand how a radical in 1959 can easily attach himself to a Labour Party led by Mr. Gaitskell.

But I will begin by attempting my own descrip- tion of a radical, so that readers may at least know what I think I am talking about. Since 1789, Englishmen of many varying views have been labelled, or labelled themselves, radicals. Faced with the contradictions in their attitudes and views, we must not be surprised if the factor which dis- tinguishes a man as a radical is one of tempera- ment, not of political principle.

First, a radical is usually an incurable romantic. Mr. Philip Toynbee came near to admitting this in his article. 'In his private life,' he wrote, the radical 'may be an arcadian : all men of passion and imagination are filled with private regrets, nostalgias and visions of a Golden Age.' But to the radical this romanticism is far more than a personal nostalgia; it underlies all his political beliefs.

Cobbett, the most characteristic of English radicals, was driven by a romantic yearning to 'recapture the childhood of the race. '. . . Now, this romanticism would revive the sentient animal in man. Animals are notoriously conservative. They like to be comfortable and undisturbed.' Cobbett was a true conservative. But he was also the leading radical of his day, and the element common to his conservatism and to his radicalism was a romantic and nostalgic conception of human nature and human society.

Secondly, and it follows from the first, the radical is usually a man with a cross-bench mind. Precisely because he tries to reconcile within him- self two apparently contradictory attitudes—a regret, for a past age of virtue and a belief that political action can help to restore it —he is likely to live uncomfortably in whichever of the two major parties he chooses, and the party he has chosen will probably have been dictated more by accidents of temperament and circumstance than by political principle.

Thirdly, and this again is a product of his romanticism, the radical is usually inspired by a profound distaste for the whole of the society into which he has been born. This is not true of the Conservative or Liberal, and it is not true of Mr. Gaitskell. These wish only to adapt existing society to their own purposes. The radical wishes to trans- form it, and he is driven by this wish even if, in moments of analytical reflection, which do not anyhow home often to him, he knows that this is impossible.

English radicalism was originally inspired and still is inspired by a loathing of the disintegrated and acquisitive society which the Industrial Revo- lution helped to create rather than by any intel- lectual attachment to the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity. The radical in 1959 is united with Cobbett in a passionate dislike of the immoral and

irresponsible expansion of wealth which the fund- lord and the speculator represent, and of the immoral and irresponsible society which they sustain to their benefit.

Fourthly, and candidly, the radical's distaste for the society in which he must live usually derives from the fact that he is personally ill adapted to it. Of the more prominent parliamentary radicals after 1832, Molesworth challenged his Cambridge tutor to a duel, Wakefield twice abducted an heiress, and Durham was so vain that even his radicalism did not prevent him from intriguing for an earldom. Choice spirits such as these may be found among the radicals of any generation : valuable rebels, certainly, but whose heady revolt against society should be taken with a dose of salts.

It is now possible to try to locate the issues with

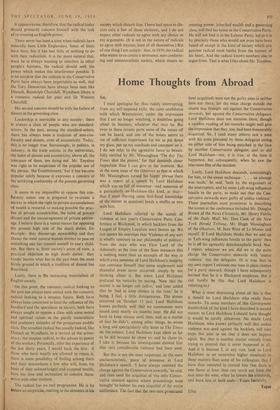

'And now while the jury are considering their verdict we're going to have a song. Yes, ladies aml gentlemen, it's your favourite and my favourite . .

which a radical in 1959 should concern himself, and determine his attitude.

He should concern himself, I suggest, with three facts : that English society is becoming increas- ingly conformist: increasingly materialistic; and increasingly violent. One need not, here, he too nostalgic about the past. The English have always been a naturally conformist, materialistic and. when occasion has incited them, violent people. What should concern the radical is that, where in the past one could hope to find dissent, an atten- tion to moral and spiritual values and a habit of non-violence, these are less and less evident, certainly less and less nourished.

The most important cause of this is the failure of most people in England to adjust themselves to the fact that their country is now a second-rate power. If. one excludes both the hysterical Right and the hysterical Left, it is fair to say that the object which the present generation has set itself is to assist in the contraction of England and to achieve this contraction with as little discomfort as possible. Whether or not this is a desirable ambition, its effects should be clearly understood, for here lies the main cause of the increasing con- formity, materialism and violence of English life.

Why, for example, concern oneself overmuch with disturbing political questions, when all the important issues are going to be decided else- where? Here is a wonderfully convenient excuse for political inaction, and not for that alone, but for moral sluggishness as well, for shrugging off all the responsibilities which membership of a great power imposes. The reason why the problem of opposing Fascism and Nazism became such an agonising one in the Thirties in England was that it was accepted that England should and could do something about it. The reason why. in the Fifties, England has escaped all the agonising re- appraisals of policy which have convulsed America is because it is no longer accepted that England can and should do something.

ThiS is true of colonial as well as foreign ques- tions. It really is asking too much to expect the English people to excite themselves about. say. the Hola Camp atrocities, when they have been taught persistently since the war that they have neither the power nor the right to exercise a decisive influence over the future of the colonial peoples whose care is entrusted to them. Gladstone could not have aroused a depressed labouring popula- tion to concern itself with the affairs of Afghanis- tan if he had not been able to persuade them that they had the power and therefore the moral right to influence events in even the most remote corner of the world.

We must face the fact, therefore, that dissent is unlikely to be found in a declining country. that genuine radicalism is a coefficient of power.

But the decline of English power has left an uglier mark. Deprived of the security which power gave .them, the English people are showing signs of becoming increasingly violent, of failing to con- fine violence to abnormal circumstances. This, again, is scarcely surprising: apart from the feel- ing of insecurity which membership of a declin- ing country naturally engenders, there is also the repressive effect of the conformity which England in her decline has been unable to avoid. Where dissent is fro‘%ned on as tasteless, or a foolhardy upsetting of the apple cart, the ingrained habit of revolt must find other outlets. It appears to me, therefore, that the radical today should primarily concern himself with the task of re-creating an Englislt power.

There never has been a time when radicals have naturally been Little Englanders. Some of them have been, but it has had little or nothing to do with their radicalism. It is far more natural that, since he is always wanting to interfere in other people's business, the radical should seek the power which makes this interference possible. It is no accident that the radicals in the Conservative Party ha'Ve always been imperialists as well, that the Tory Democrats have always been men like Disraeli, Randolph Churchill, Wyndham (there is a romantic radical for you) and Sir Winston Churchill.

His second concern should be with the failure of dissent in the governing class.

Leadership is inevitable in any society : there is always a class of people who are standard- setters. In the past, among the standard-setters, there has always been a tradition of non-con- formity and dissent, even of eccentricity. Today, this is no longer true. Increasingly, in politics, in industry, in the trade unions, in the universities, the habit of dissent and eccentricity, above all, the tolerance of them, are dying out. Mr. Toynbee was right to be suspicious of the popular use of the phrase, 'the Establishment,' but it has become popular solely because it expresses a concern at the terrifying conformity of the present governing class.

It seems to me impossible to oppose this con- formity unless one is prepared to re-create a society in which the right to private accumulations of wealth is restored, so making possible the prac- tice of private eccentricities, the habit of private dissent and the encouragement of private patron- age. I believe there is a moral reason for opposing the present high rate of the death duties, for

example : they discourage stewardship and they

thwart the most natural human instinct to pass on something one has created oneself to one's child- ren. But there is. from society's point of view, a practical objection to high death duties: they render barren what has in the past been the most fertile ground in which a tradition of dissent has flourished.

Lastly, there is the increasing materialism of English society.

On this point, the romantic radical looking to the past has always been united with the romantic radical looking to a utopian future. Both have always been concerned to limit the influence of the fundlord and the speculator in society, both have always sought to oppose a class with some moral and spiritual values .to the purely materialistic and predatory attitudes of the prosperous middle class. The arcadian radical has usually looked, like Disraeli or Wyndham, to a revival of the aristo- cracy; the utopian radical, to the advent to power of the workers. Personally, after the experience of the last thirty years, I would back the first : if those who have wealth are allowed to retain it, there is some possibility of finding among them and their descendants a few who will, from the basis of their acknowledged and accepted wealth, have the time and inclination to concern them- selves with other matters.

The radical has no real programme. He is by nature an empiricist, reacting to the elements in his society which disturb him. I have had space to dis- cuss only a few of those elements, and I do not expect other radicals to agree with my choice or my arguments. (It is not in the nature of radicals to agree with anyone, least of all themselves.) But of one thing I am certain : that, in 1959, the radical who wants to re-create a strenuous, non-conform- ing and unmaterialistic society, which means re- creating power, inherited wealth and a governing class, will find his home in the Conservative Party. He will not find it in the Labour Party, led as it is by precisely those who would not even have been heard of except in the kind of society which any genuine radical must loathe from the bottom of his heart. And the radical knows nowhere else to argue from. That is what Hike about Mr. Toynbee.

Previous page

Previous page